U.S. Supreme Court (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

Not to make testy judgments about judges, but restraint doesn't come easy when headlines like these keep showing up: "When Juries Say Life and Judges Say Death" and "Republican-appointed Judges Give Black Defendants Longer Sentences, Study Finds."

Infecting this injudiciousness still more are the nine robed ones on the Supreme Court who rarely reach a 9-0 consensus while predictably squaring off, with five conservatives interpreting the law one way and the four liberals another. We aren't a nation of laws, we're a nation with certain people deciding laws.

And then the television clowns: Judge Judy, Judge Jeanine, Judge Joe Brown.

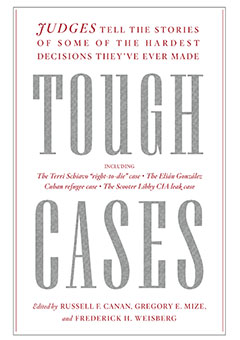

To ward off despairing at this morass, we have Tough Cases and its engaging and bracingly honest essays by 13 trial judges. The editors themselves, Russell F. Canan, Gregory E. Mize and Frederick H. Weisberg, do their fallible ruling from the bench at the District of Columbia Superior Court, where everyone from the homicidal to the civilly disobedient recidivists have their verdicts imposed by more than four dozen judges. The tough cases, the editors write, involve "the rare times in a judicial career when a judge has to wrestle with a problem so complex, or so emotionally draining, as to test the fortitude and impartiality of even the most competent and experience jurists."

A judge whose emotions were most severely drained is George W. Greer, who served in the family law division of the Pinellas-Pasco County Circuit Court in Florida. In late January 2000, he was the presiding judge assigned to decide the fate of Terri Schiavo, a married woman who had collapsed in her early 20s from cardiac arrest and would never regain consciousness. She had been kept alive in a persistent vegetative state for a decade. Based on evidence that Schiavo "would have chosen to remove her feeding and hydration tube," Greer ruled favorably for her (guardian) husband's petition to end the life supports.

The condemnatory backlash was immediate. Members of Congress smeared Greer as a murderer and terrorist. President George W. Bush, his brother Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, and Jerry Falwell Sr. took their swipes. The future saint Pope John Paul II also butted in. Two critics were arrested for making death threats. For months, police guarded the judge's home. Topping it off, and what was the most personally painful sting, Greer received a letter from his Baptist pastor booting him from the church.

After 14 appeals and five suits in federal courts, Schiavo was allowed to die in 2005. Greer writes of the "high costs" of toughing it out as the decisional judge: "Not too many people have to stand up to their president, their congress, their governor, their legislature, and their church. And I would never have known for sure if I had the strength to do that if not for this case."

Introspection runs thematically through the well-tuned essays, and especially in the sentencing phases of criminal trials. Canan, appointed to the Superior Court of the District of Columbia in 1993 by President Bill Clinton, had before him a defendant in his 40s, employed, with no prior convictions, charged with assault with a dangerous weapon and assault with intent to kill while armed. Hearing prosecution and defense lawyers theatrically slug it out, Canan found himself convinced of the man's innocence:

Had the case been tried before me without a jury, I would have found him not guilty on both charges. It looked like I was going to have to accept a verdict that I personally disagreed with. This happens occasionally, though most of the time I agree with the jury's verdict, or, if not, I understand how they came to their conclusion in a rational way. … Simply put, the jury is the judge of the facts. The trial judge determines the law; the jury finds the facts, and the court must defer to the jury's judgment on them.

In the end, Canan summoned the lawyers to his chambers to "strongly urge both sides" to consider a plea bargain. A deal was reached: a guilty plea on one charge and the other dropped. Coincidentally, the defendant's plea was reached while the jury was deliberating and would have come back with not guilty verdicts. Canan had unsettling misgivings that he had "crossed a line" while questioning the defendant during his plea and unnerved him with the threat of five years' hard time. His astute lawyer filed a motion that the plea was made under "intense pressure."

Canan, acknowledging that "I had orchestrated a turn of events that scared" the defendant, granted the motion.

Advertisement

Well removed from what can look like assembly-line justice in over-busy urban courts is the rural court of Judge Allie Greenleaf Maldonado in Petoskey, Michigan:

As the chief judge for the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians I have limited jurisdiction, and I rarely hear the serious drug cases that routinely plague big cities. … People in this small community expect to feel safe. So, when one of our young women, whom I will call Salmon Running, allowed herself to be used by a downstate drug dealer to sell heroin and cocaine from the Tribe's hotel, it was a big deal.

At 23, Running ended up before Maldonado, a former litigator for the federal Department of Justice. When Running failed to appear for a pretrial status conference, Maldonado learned she had fled to Florida and was serving a year sentence. Brought back to Northern Michigan, she was placed on probation, but "just over one month after giving her an opportunity to change her life," Maldonado writes, "she tested positive for drugs. I was crushed. It looked like I was wrong to give her second chance."

Instead of imprisoning Running, the judge went with a third chance by enrolling her in a yearlong drug court rehab program. She wondered: "Would I look like a weak, bleeding heart jurist unfit for the bench?" If so, it didn't matter. Running responded well and, changing her ways, has been sober for years, leading her judge to say: "Salmon Running's story has also changed me. On days when I am most challenged to see the possibility of change in tribal citizens, I think of her, and I know that if the person in front of me truly believes they can transform their life, I should take a risk and believe too."

The editors of Tough Cases chose well to find judges of heart and skill, bringing their stories to light.

[Colman McCarthy's forthcoming book is Opening Minds, Stirring Hearts.]