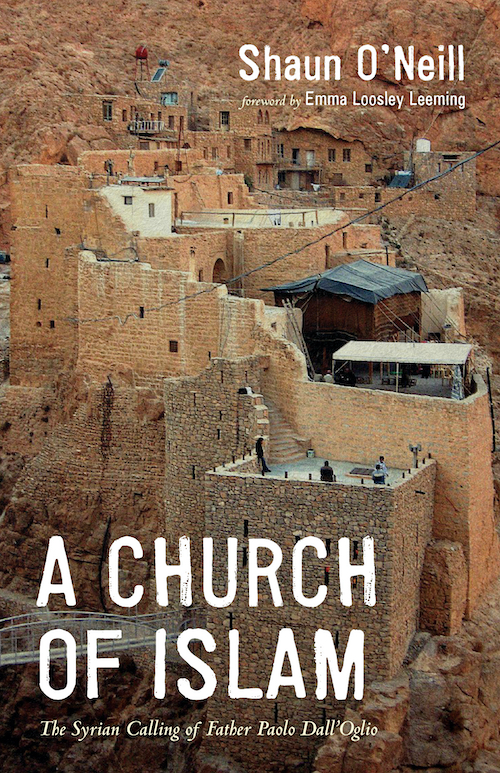

Winding steps ascend to Deir Mar Musa al Habashi, the monastery of Saint Moses the Abyssinian, in Nabk, Syria, approximately 80 km north of Damascus. (Gabe Huck, Theresa Kubasak)

Cover art for "A Church of Islam" (Wipf & Stock)

This Paolo Dall'Oglio of the subtitle above, an Italian by birth, became a Jesuit, a scholar of Islam and a fluent speaker of Arabic. Beginning in the 1980s for 30 years, Paolo sought a dialogue among Muslims and Christians in Syria. This dialogue was mostly informal but it had its scholarly side also. Paolo began, often alone, by embracing the labor of reviving, stone by stone, a monastic building that had been abandoned 100 years earlier. High on a mountain that looks east to the Syrian desert, this monastery may have been first built in Roman times as a military watchtower to keep an eye on possible invaders.

When we began living in Syria in 2005, we would often be asked if we had visited Deir Mar Musa al Habashi: the monastery of Saint Moses the Abyssinian, this "Moses" being the legendary founder of several monasteries on his travels from eastern Africa to Roman Syria. By the time we left Syria in 2012, we had often traveled by bus an hour north from Damascus to visit this religious community.

We came to know Paolo and many of the men and women in the monastic community. If we had visitors from the U.S., we took them there. Where else to see on the walls of a church, built 1,500 years ago, frescoes painted in the 11th and 12th centuries? Often our Iraqi students came with us to visit Mar Musa. Those students were among the hundreds of thousands of Iraqis who sought safety in Syria during the U.S. occupation of Iraq. We climbed winding steps ascending finally to the monastery, then bent low to pass through the entryway and so enter to the busy — or silent — courtyard and be welcomed.

A quote from Paolo's writings is helpful here. Note the litany he calls forth of our Christian ancestors who grasped something of this bond between Muslims and Christians:

We live our vocation building on this extremely rich experience of Christian witness accumulated by the Oriental Churches in common life with Muslims for fourteen centuries and deeply harmonized with them through the Arabic language. And we walk on the path of Francis of Assisi, Ignatius of Loyola, Charles de Foucauld, Louis Massignon and Mary Kahil, feeling the love of Jesus to each Muslim man and woman. We now consider Islam as being the human group to which we belong and in which we are happy to live, thankful that we have been chosen by God to participate in the life of the ummah [the Muslim people]… . We understand the monastery as the spiritual home of those Christians, disciples of Christ, who feel a vocation of deep and humble love for Muslims and for Islam, as much as a spiritual port for Muslims feeling a vocation for deep friendship with Christians. For both it is a place of harmony and a prophecy for peace in our region and further than that.

Advertisement

We could add to Paolo's roll call of Christians who had embraced the Muslim community the Trappist monks of Algeria whose story is told in an excellent film, "Of Gods and Men," and in The Monks of Tibhirine by John W. Kiser.

In early 2011, non-violent protests against the Syrian government began and spread through Syria, especially happening after noon prayer on Fridays. Friday by Friday, these were answered with violence from the government. Paolo called for an end to the violence and for government/citizen talks. But gradually there was violence on all sides, though non-violent witness continued — and continued to bring violent response from the government. Soon other nations were sending military forces to take one side or the other.

The Syrian authorities ordered Paolo to leave Syria in the summer of 2012. While outside Syria, Paolo took a stance against the Syrian government. In 2013, Paolo returned to Syria, apparently crossing the border from Turkey. At least part of his intention was to intercede for the release of several persons who had become prisoners of those sometimes called ISIS and sometimes Daesh. Paolo did not return from Syria. For years, many hoped that he was still alive, perhaps being held as a hostage to be used in the future. Such hope seems unlikely now.

Southwest arch and west wall of the Deir Mar Musa al Habashi church (Gabe Huck, Theresa Kubasak)

A Church of Islam by Shaun O'Neill is the first book in English to tell the story of Paolo and other members of the community and their approach to conversation between Islam and Christianity. "Conversation" here embraces a deep respect, each for the other. And the conversation over years embraces not the history only, but the very fabric of being a Muslim or of being a follower of Jesus.

O'Neill met Paolo only once when O'Neill was visiting Syria just before the 2011 protests began. He tells us that he visited Deir Mar Musa after "a casual recommendation from a friend in Damascus." With many other visitors arriving that day, O'Neill met the monks and nuns of the community, met Paolo briefly, stayed the night — and went back to Damascus with much to think about. He pursued his studies in Sweden and stayed in contact with the monastic communities in Syria and later in Iraq, all of them related to the Mar Musa experience. The author clearly respects the community, knows that the two-plus decades of women and men committing themselves to the vision Paolo and others articulated is vital and important beyond Syria.

A few cautions then. The title seems to us confusing: A Church of Islam. What is the "of" meant to convey? Paolo once wrote: "I started to think how to transform the presence of the Church in the Islamic world into a Church for the Islamic World."

It is alarming to be told by the author that his book has "creative non-fiction elements." What does that mean? Another problem: No index. Rather there is a bibliography that is amazingly confusing. And footnotes galore, many unnecessary. This is why authors need publishers and publishers need editors.

The last book Paolo wrote and published (in French) was Amoureux de l'Islam, croyant en Jésus. The title sums up Paolo Dall'Oglio: In love with Islam, believing in Jesus.

[Gabe Huck and Theresa Kubasak are the authors of Never Can I Write of Damascus: When Syria Became Our Home (Just World Books).]

Editor's note: Love books? Sign up for NCR's Book Club list and we'll email you new book reviews every week.