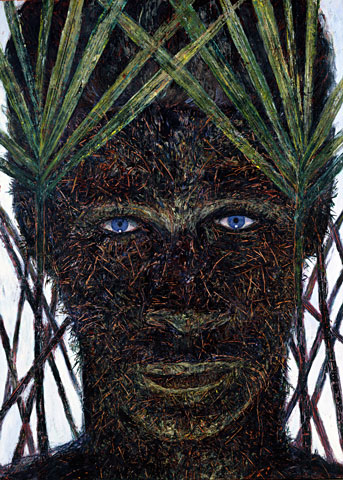

Arnaldo Roche Rabell, "We Have to Dream in Blue" ("Hay que soñar en azul"), 1986, oil on canvas

For a good while now, traditional boundaries and divisions in art have been fading or becoming ambiguous. Life and art, the world and the way we imagine it increasingly interpenetrate one another. Schooled and self-taught art, fine and everyday folk art, realistic and abstract, even religious and secular have all become too often misleading distinctions, an unfortunate surrender to Western culture's scientific bent toward defining and categorizing experiences and objects that in fact defy explanation.

With the realization of how porous the apparently different aspects of life and art can be have also come less welcome developments -- reductionist views that everyone is an artist or that anything can be art, the triumphantly capitalist convictions that cash value determines the work of art and that the market establishes the hierarchy of its importance. Even critics who champion diversity and oppose all hierarchies are all but unanimous today in denouncing the mounting commercialism in the world market of art.

Then along comes an exhibition, mounted cooperatively by three of New York City's smaller museums, that encourages visitors to see, as if for the first time, a whole region of the world in the multiple strands of its expression -- delighting the eye, challenging preconceptions, leading on a journey of exploration with as many questions as answers. "Caribbean: Crossroads of the World," organized by a team of nine scholars and curators at The Studio Museum in Harlem, El Museo del Barrio, and the Queens Museum of Art is the show, and it is a stunner -- aesthetically, culturally and, indeed, ethically. Elvis Fuentes of El Museo was the lead curator.

If you've been lucky enough to visit anywhere in the Caribbean, you are unlikely to have recognized the deep blend of European, African, North American, Asian and of course Latin American influences that went into preparing your experience. Here they are!

The story, or, better said, collection of stories (as in the Bible), is told in six chapters, two at each venue, beginning with the Haitian Revolution of 1791 (it lasted till 1804) and continuing to the present.

The Studio Museum exhibit closed on Oct. 21, but the exhibits at the other venues continue to Jan. 6 next year.

At the Studio Museum, the large central gallery was masterfully arranged, artfully mixing paintings, prints, sculpture, video and display cases to explore "Shades of History," an examination of the role of race in the region's history. A rare late-18th-century drawing by Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson presented the former slave and revolutionary abolitionist Jean-Baptiste Belley, elected to represent the colonies at the French National Convention during the Revolution. Sculpture ranged from a classically sleek marble bust of Napoleon by Canova (1802), evoking both French neoclassicism and colonialism, to Jamaican artist Mallica Reynolds' achingly expressionist "Seven Brothers," in wood (1966), with seven heads springing from a single base, solidarity in their suffering.

The Studio's smaller, parallel gallery, titled "Land of the Outlaw," presented the Caribbean's ambiguity as both Edenic and dangerous. There, early-19th-century scenes of European travelers mixed with contemporary irreverences such as FEEGZ's "Jewish Zombie" (2011), on which is inscribed "Hate Being Told My Salvation Only Comes Through the Jewish Zombie" -- one of the more extreme indications of how imported Catholicism has permeated the Caribbean.

Then there was the enchanting "El Bibliobandido," a mythic mixed-media piece in which Marisa Jahn and colleagues create a marauding bandit who terrifies illiterate children in northwest Honduras into telling stories he will steal -- and thus awakens them to a world of imagination and creativity.

At El Museo, a further chapter ("Counterpoints") explores the tensions caused by economic developments -- from sugar plantations, to the tobacco industry, to the conflict between increasing oil exploration and tourism.

It begins with a smashing large oil on canvas, "We Have to Dream in Blue" (1986), a self-portrait of the Puerto Rican artist Arnaldo Roche Rabell (born 1955), whose camouflaged face with its dark, vegetal skin and sapphire blue eyes is framed by sugar cane. The painting hangs close to Esteban Chartrand's "Yumuri Valley" (circa 1877), depicting a Cuban sugar plantation almost a century earlier. The pioneering self-taught artist Hector Hyppolite shows us what a "Banana Boat" looked like in Haiti (circa 1945). As evidence of luxury trade, the Colombian Olga de Amaral weaves a dazzling tapestry with gold leaf, "Lunar Basket" (1999).

How did the various emerging nations in the region understand and identify themselves? In the provocatively titled next chapter, "Patriot Acts," three of El Museo's intimate galleries respond to the question with vigor and variety through landscape, portraiture, sculpture and video. The wealth of material includes Enrique Grau Araújo's "Mulata Cartagenera" (1940), drawing on European tradition but re-imagining it for a voluptuous young Colombian woman. In one of his mystically delicate landscapes, the great Venezuelan Armando Reverón shows us "Light Viewed Through My Vine Plants" (1926). Armando Morales Sequeira, who was born in Nicaragua and died in Miami (another Caribbean city), paints a largely abstract, religiously evocative "Spook Tree" (1956).

In a thoroughly enjoyable video that reverberates with multiple meanings, the young Danish artist Jeannette Ehlers tapes herself in "Three Steps of Story" (2009) in the grandiose, mirrored hall of Government House in St. Croix where she dances to "The Skater's Waltz" -- in sneakers.

The notion of "Caribbean" is clearly fluid, ranging from geographical (the immediate basin of the sea but also the diaspora) to cultural and poetic senses. The centrality of the sea comes to the fore in "Fluid Motions," chapter five of the story at the Queens Museum of Art.

Here you see images of fishermen, sailors and mermaids, warships, sailboats and ferries, underwater diving, a burial at sea and the rivers that empty into "el Mar Caribe." There's a glorious Leo Matiz photograph of an enormous net being cast by a sturdy young fisherman, "Peacock from the Sea" (1939), and Hyppolite returns with the densely symbolic painting "National Flag" (before 1948).

The gallery also includes some socially keen pieces: the Cuban Alejandro Aguilera's tribute to "El Che y Carlos Santana" (2006), merging the two mythic figures in a Rauschenberg-like combine; Yubi Kirindongo, a sculptor from Curaçao, who uses chrome automobile bumpers, à la John Chamberlain, to forge "The Beast" (1991); and the Costa Rican Rafael Ottón Solís Quirós' powerful "Homage to Monsignor Romero" (1983), again resembling a Rauschenberg combine, with a red cincture indicating who suffered the violence the work so forcefully conveys.

With more than 500 pieces in all,

500 pieces in all,

more than half of which are shown in Queens, "Caribbean: Crossroads of the World" is a sprawling, seductive show. Its final chapter, "Kingdoms of this World," brings to heated life all the bursting exuberance, colorful performance and omnipresent music that we associate perhaps most of all with the region.

Two huge Carnival costumes dominate the central gallery, and representations of the event range from the Dominican Tam Joseph's large, acerbic acrylic on paper "Spirit of the Carnival (The British forces of law and order in confrontation with an ancient African Spirit)" (1982), to the Cuban René Portocarrero's elegant, Miró-like abstraction, "Cuban Carnival" (1953). There are also paintings of the Virgin, various saints (St. Anthony, St. Ignatius of Loyola), and unnamed nuns. The piety oscillates between satiric and sincere.

Smaller surrounding galleries offer some outstanding work as well. The Cuban Sandra Ceballos' "Absolut Delaunay" (1995), for example, or the great Romare Bearden's "Eden Noon" (1998), which is, simply, Edenic. And as moving as anything in the entire exhibition is the Dominican David Perez Karmadavis' "Complete Structure" (2012), a four-minute, 42-second video that shows a blind Dominican man carrying a Haitian woman without legs through the town of Santiago de los Caballeros in the Dominican Republic. He speaks only Spanish, she French. The sense of complete interdependence is breathtaking. And while Dominicans are predominant in the neighborhood of the museum, I understand that "Caribbean" has drawn more Haitian visitors than usual and that many watch this piece repeatedly.

There's so much in this exhibition, in fact, that you'd like to look at repeatedly. You also intuit a great deal, and wonder still more. The individual wall labels are quite terse. But that is as it should be. The show is meant to affect the way we imagine the Caribbean -- as place and idea, culture and challenge. But it inevitably also deepens the current argument for the creative diversity of cultures.

A more open appreciation and a keener eye for the as yet unseen is the gift you receive for attending these exhibitions. A clear theological lesson here is that centralized and authoritarian thinking cannot do justice to the wonderful variety of God's creation and God's people in it.

[Jesuit Fr. Leo O'Donovan is president emeritus of Georgetown University in Washington and a frequent commentator on the arts for NCR.]

Exhibit information

"Caribbean: Crossroads of the World" (caribbeancrossroads.org) remains at El Museo del Barrio and at Queens Museum of Art through Jan. 6, 2013. A book, Caribbean: Art at the Crossroads of the World, edited by Deborah Cullen and Elvis Fuentes, with 500 color illustrations and essays by leading scholars, was published by Yale University Press in November.