Holy Cross Fr. John Jenkins, president of the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, is pictured in an undated photo. (OSV News/Courtesy of University of Notre Dame)

By the time Fr. John Jenkins took over as president of the University of Notre Dame in 2005, millions of television viewers were already familiar with U.S. President Jed Bartlet, a proud "Domer," who often wore his university-branded apparel in the Oval Office and openly wrestled with what it means to be a Catholic in public life.

In the wildly popular "West Wing" series, which began its final season during Jenkins' first year as the university's president, a Notre Dame alumnus that had become the American president was mere fiction.

But today, one of President Donald Trump's most polarizing Supreme Court picks, Justice Amy Coney Barrett, is both a Notre Dame graduate and former faculty member, and one of President Joe Biden's most visible Cabinet members (and onetime presidential rival), Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg, has long been affiliated with the university.

"It's a mixed blessing," Jenkins said with a lighthearted laugh during a Jan. 28 interview with the National Catholic Reporter.

What he hopes this sort of notoriety conveys, he said, is that "whatever the issue is, Notre Dame opens doors. It just does."

'A Catholic university in the richest, broadest sense is something the world needs and the church needs.'

—Holy Cross Fr. John Jenkins

The Holy Cross priest has served 19 years as the university's president and will step down at the end of this academic year. Jenkins spoke to NCR during a visit here in January, when the university's Rome Global Gateway conferred honorary degrees to a prominent Italian filmmaker, the director of the Vatican Museums, and a prominent bishop who helps oversee the Catholic Church's ecumenical efforts.

A few days later, on Feb. 1, a delegation from the university was received in a special audience with Pope Francis.

While the university's home campus may be located in South Bend, Indiana, it has no difficulties opening doors at the center of the church and has expanded its footprint to more than 10 cities around the world. What began as humble missionary beginnings in 1842, with aspirations of becoming a "great Catholic university in America," has now become an institution known throughout global Catholicism.

'Lightning rod' of Catholic identity

Under Jenkins' tenure, the university now boasts of an increasingly diverse and high-ranking student body, a financial endowment of approximately $20 billion, and, as of 2023, inclusion in the Association of American Universities, a consortium representing the country's leading public and private research universities.

A statue of the Virgin Mary stands atop the Golden Dome at the University of Notre Dame. (Unsplash/Steven Van Elk)

"I am proud that while we made that progress by the ordinary measures of what a university is, we've been able to kind of navigate what being a Catholic university is," said Jenkins, when asked about his proudest achievements over the last two decades.

Catholic identity can be a "lightning rod," he acknowledged, with various constituencies seeking to impose their own definition of what it means at Notre Dame.

"I believe the world does not necessarily need another prestigious university," said Jenkins. "But a Catholic university in the richest, broadest sense is something the world needs and the church needs."

"Not everyone's Catholic, not everyone on campus is religious, but there's a wide sense that we need to be different and it needs to be reflected in what we do," he added.

There's not just an open debate about what it means to be a Catholic university these days. In recent months, there's been a national contest over the very nature of what it means to be a university.

The high-profile resignations of the presidents of Harvard and the University of Pennsylvania — following congressional testimonies that ignited fierce backlash over their seeming inability to answer questions as to whether protests advocating the genocide of Jews violated their school's codes of conduct — have put many elite educational institutions in the crosshairs.

While Jenkins said he has no desire to wade into the particulars of these cases, he's adamant that higher education must be oriented toward objective truth.

"Once you divorce education from a broad understanding of what it is to live a broad, good, full human life, it becomes attenuated, it becomes hard to make decisions," he said.

Advertisement

And a Catholic institution, he believes, helps provide the necessary moral framework to better evaluate some of the hot-button concerns in political life today.

The distinguishing — indeed, the central — aspect of Catholic education, according to Jenkins, is that "there is a respect for religious faith, not just Catholic, but others, and there's a sense that the highest level of reason and inquiry can go along with our faith."

"I think you'll find the assumption in other places that they're incompatible," he added.

Among the most contentious topics roiling college campuses today are questions surrounding free speech and tensions related to diversity, equity and inclusion efforts (better known as DEI initiatives).

On these questions, as well, Jenkins insists there has to be a Catholic difference.

"In a broad Catholic moral framework, our interdependence is central, as is the dignity of every human being, regardless of race, nationality, ability, sexual orientation, anything else. Everybody needs to be respected and we rely on one another, and we have to have special care for the marginalized and for those who are vulnerable," he explained.

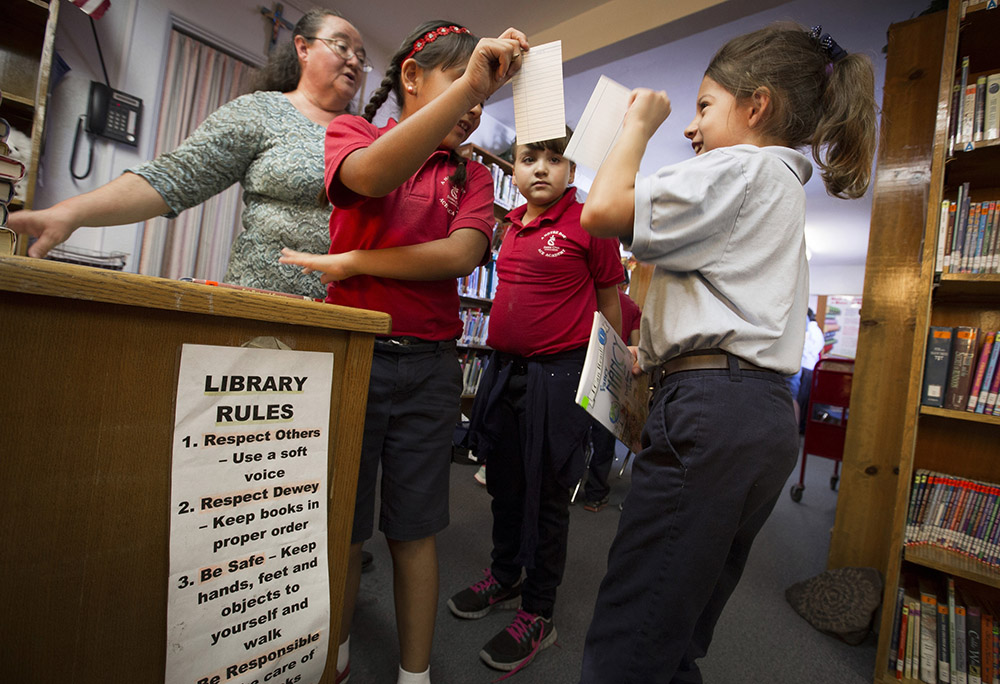

Students check out books in the library at Santa Cruz Catholic School, a Notre Dame ACE Academy in Tucson, Arizona, Oct. 22, 2014. Santa Cruz was on the verge of closing when the University of Notre Dame's Alliance for Catholic Education stepped in to boost enrollment and academics, help the schools achieve financial stability and bolster their Catholic mission. (CNS/Nancy Wiechec)

"Those three pillars of Catholic social teaching come together in DEI and the goal is to build a community where everyone is respected and everyone can flourish," Jenkins said.

But he offered a caveat: "My worry is that if you divorce DEI from a broader understanding of the human person and society, it does become ideology," he said. "It does degenerate a little bit into the latest fashionable marginalized group who we want to help and that changes with time."

While he said the values of diversity, equity and inclusion are all necessary, "it's a matter of being rooted in the Catholic ethos."

At a time when there's no shortage of protests by activists on both the left and the right regarding campus speakers, Jenkins said that he's especially proud that in his nearly two decades as president, no speaker has been unable to finish their talk because they've been shouted down or disinvited from campus.

"Why is that?" he asked aloud. "I'd like to think the Catholic framework gives us a mutual respect and a sense of calling us to something higher that allows the debate to continue."

Keri Kei Shibata, director of University Police, and Holy Cross Fr. John Jenkins, president of the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, lead guests to the Grotto June 1, 2020, during the "Pray for Unity, Walk for Justice" event in memory of George Floyd on the campus near South Bend. (CNS/South Bend Tribune via Reuters/Michael Caterina)

A philosopher by training (with degrees in the field from, naturally, Notre Dame, as well as Oxford), he points the finger at the likes of philosophers Friedrich Nietzsche and Michel Foucault, who both broadly questioned whether reason can solve clashes of power.

"If you believe that, then the only sort of thing to do is to try and crush your opponent. You just want to grab power from your opponent," he said. "But if you have an understanding of human beings and human reason that there is the possibility of having debate and where we disagree, we can disagree strongly, but we can listen to one another."

"At the heart of the Catholic view of the world is a very deep social sense that we're interdependent," Jenkins continued. "That's the common good, that we need one another, that we have to find a sort of society where everyone can flourish. I think at its best that infuses a Catholic university and at its best you don't have to feel the need to crush your opponent."

Obama, Biden, Boehner — and Pope Francis

Yet those ideals espoused by Jenkins have been put to the test quite strongly in his own backyard.

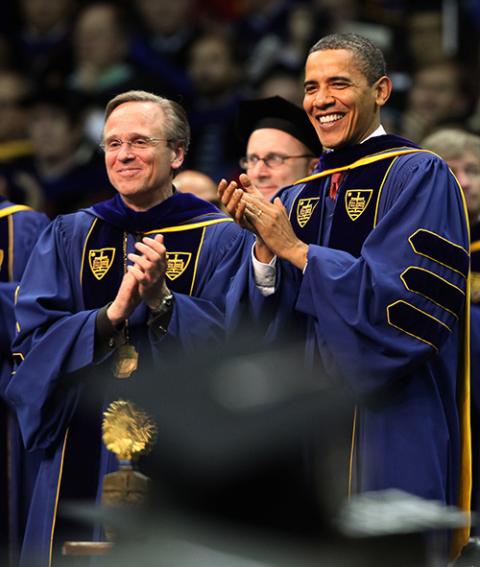

Jenkins' invitation to President Barack Obama to deliver the 2009 commencement address at Notre Dame and receive an honorary doctorate sparked protests from student groups and some prominent national Catholic voices.

Chicago resident and Notre Dame alumnus Jeff Heinz, right, drops his handwritten letter to University of Notre Dame President Holy Cross Fr. John Jenkins into a box April 5, 2009, during a rally at the university in Notre Dame, Indiana. Hundreds of anti-abortion advocates protested on the campus against the school's invitation to President Barack Obama to speak at the May 17 graduation ceremony that year. (CNS/Jon L. Hendricks)

In 2016, he waded into the same divisive waters by inviting both former Speaker of the House John Boehner, a Republican, and then-Vice President Joe Biden, a Democrat, to receive the Laetare Medal, arguably the highest honor in American Catholic life.

Both occasions drew sharp criticism, including from some Catholic bishops, who fiercely objected to the university honoring politicians, like Obama and Biden, who support legal abortion.

Reflecting back on those incidents, Jenkins attributed the fallout to the increasing polarization among American Catholics, where political affiliation is more likely to affect one's views rather than their faith.

Jenkins recalled his own upbringing where the local Catholic parish served as a melting pot of individuals of all political persuasions, but where they still managed to come together around their faith.

"I think we've just segregated ourselves," he lamented.

Holy Cross Fr. John Jenkins and U.S. President Barack Obama applaud during the commencement ceremony at the University of Notre Dame in Notre Dame, Indiana, May 17, 2009. Obama was the commencement speaker and honorary degree recipient. (CNS/Christopher Smith)

Despite the university's long history of hosting more presidential visits for commencement than any institution of higher learning other than the military academies, it has not extended that invitation to Biden.

While Jenkins' praised the president's openness about his personal faith, he conceded that the long shadow of the Obama visit is "perhaps a little" of the reason why the nation's second Catholic president has not been invited to campus.

"It was toxic and divisive in 2009 when we had Obama and it just seems to have increased," Jenkins said.

Those tensions, he acknowledged, are also present in certain pockets of the U.S. Catholic Church, particularly over its reception of Pope Francis. Jenkins said it was regrettable that there have been certain special interest groups in the church who have tried to focus solely on questions regarding gay marriage or abortion.

Francis, said Jenkins, has "spoken from the heart of the faith" on the broad range of Catholic concerns. "He's made it a range of issues. It's not simply abortion. It's climate change; it's migration."

That, he said, has been good, not just for the whole church, but particularly at Notre Dame.

"He's certainly made it possible for us at Notre Dame to engage the whole range of issues and engage the world in a way, which is what he wants us to do, to not just be intramural Catholic all the time," said Jenkins.

As he looks back on his tenure, the 70-year-old Jenkins seems neither nostalgic nor unsentimental.

On Sept. 26, 2020, in the Rose Garden at the White House in Washington, President Donald Trump arrives with Judge Amy Coney Barrett for a news conference to announce Barrett as his nominee to the Supreme Court. (AP/Alex Brandon)

When asked if there are any decisions he'd like to revisit, he is quick to reply "a certain visit to the Rose Garden," referring to his September 2020 visit to the White House ceremony where Trump presented Coney Barrett as his nominee to succeed the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the Supreme Court.

The event turned into a COVID-19 superspreader event, where both Trump and Jenkins, along with more than a dozen others, contracted the virus. Jenkins faced immediate criticism from faculty and students for not adhering to recommended protocols at the time, including mask wearing.

"It was a bad decision by me," Jenkins admitted. "It was embarrassing. It was dumb and I shouldn't have done it."

But taking stock of nearly 20 years in one of the top jobs in the U.S. Catholic Church, he says one of his chief feelings is that of gratitude for a job that has allowed him to work through some of the critical issues facing both the church and the country and try to speak to them on a national stage.

To do so as both a president and a priest, he says, is a unique combination.

"It's about bringing a group together — the whole university, faculty and staff — around the mission, and it's a priestly role," said Jenkins. "It goes deeply to who I am."

Pope Francis with an audience from the University of Notre Dame on Feb. 1. At right is Holy Cross Fr. John Jenkins and at left is Holy Cross Fr. Robert Dowd, who will succeed Jenkins as president of the university in July. (Courtesy of University of Notre Dame/Vatican Media)

In July, Jenkins will be succeeded by fellow Holy Cross priest Fr. Robert Dowd. At a time when many Catholic universities are increasingly handing over the reins to lay leaders, Jenkins said he still sees a strong value in Notre Dame being led by a member of its founding order.

"The asset we have is the mission. To align that mission with someone who has a vocation as a religious and as a priest, that's powerful," he said. "What you can contribute as a priest-president is a personal embodiment of that mission. That's invaluable."

Aware that higher education is rapidly changing, the United States is changing and the global Catholic Church is changing, Jenkins said his advice to his successor is the same advice he received: steadiness.

And also, take a cue from Pope Francis, who Jenkins said believes "the church cannot be insular and it must engage culture."

"I hope we can do that, too," he said. "And I think we can."