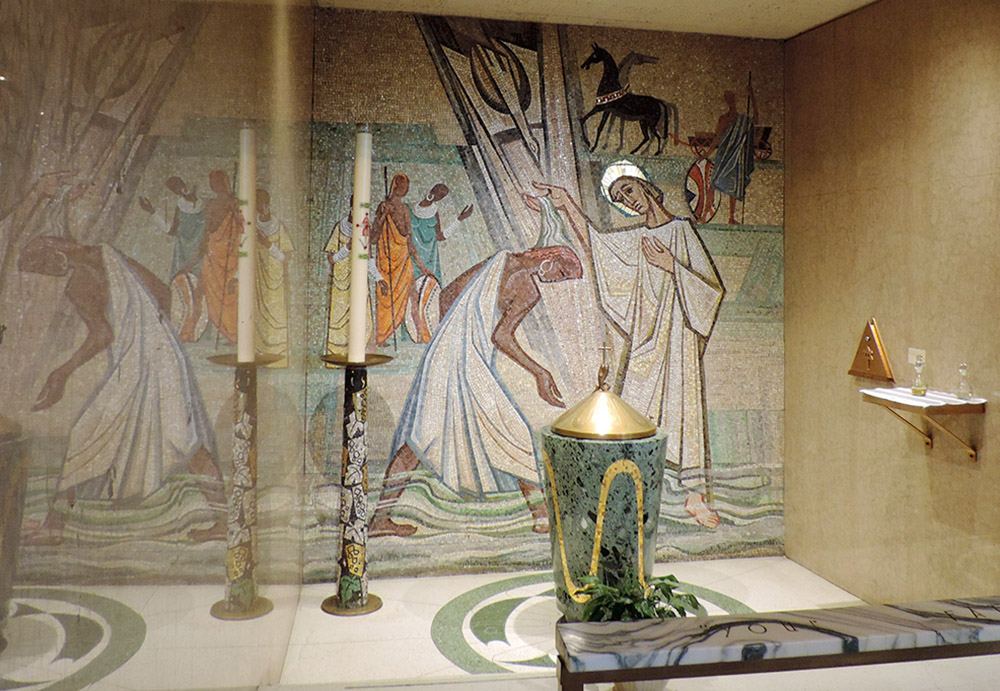

Baptistry mosaics and brass works by artist Peter Recker are seen at St. Rita Catholic Church in Indianapolis March 6. St. Rita is one of 16 Christian churches to receive a grant from the National Fund for Sacred Places. (OSV News/Courtesy of National Fund for Sacred Places/Caleb Legg)

St. Rita Parish on Indianapolis' east side is a community of firsts and of unique contributions — starting with its founding in 1919 as the first designated Black Catholic parish in Indiana.

It was the first archdiocesan parish to offer kindergarten and accredited day care. It sponsored Indianapolis' first interracial, parochial versus public high school football game. Its boxing club produced three-time light heavyweight world champion Marvin Johnson.

"Nationally recognized architectural and artistic significance" can now be added to that list. The parish's church stands not only as an important example of Mid-Century Modern architecture, but also as what is possibly the world's largest collection of art works by Peter Recker, a globally renowned Catholic artist of the mid-1900s.

"We're a hidden gem," said Caleb Legg, a historian, architecture expert and member of St. Rita.

He is not the only one who thinks so. Recently, the parish was selected to apply for — and received — several elite preservation grants and is under consideration to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

St. Rita Catholic Church in Indianapolis is seen March 5. (CNS/Courtesy of National Fund for Sacred Places/Caleb Legg)

These accomplishments recognize the parish's religious, social, cultural, architectural and historic impact — an impact that began at a critical time for Black Catholics.

One hundred years ago, "Indiana was at the height of the segregation movement," Legg told The Criterion, Indianapolis' archdiocesan newspaper. "The [Ku Klux] Klan was extremely powerful. Given that we were both Black and Catholic, we had a double target on our backs."

And with many parishes of the time still affiliated by nationality such as German, Irish and Italian, "there really was no place" for Black Catholics to call their faith home, he explained. The creation of the parish by then-Bishop Joseph Chartrand in 1919 was "a tremendous show of church support and sympathy to the needs of Black Catholics," said Legg.

Since its founding, the faith community has been building what he calls a "forward-thinking legacy."

Much of that legacy occurred under the leadership of Fr. Bernard Strange, the parish's administrator, associate pastor, then pastor from 1935 to 1973.

The interior of St. Rita Catholic Church in Indianapolis (CNS/Courtesy of National Fund for Sacred Places/Caleb Legg)

According to Legg's research, some of the white priest's accomplishments at the parish and its former school include obtaining the right of Black girls to attend local Catholic high schools, instituting a tuition payment plan for financially challenged families, including roller skating lanes in the school's gym, and creating the archdiocese's first dedicated school library.

Strange's greatest physical legacy is the parish's Mid-Century Modern church, built from 1958 to 1959.

"He believed in working hard and earning your way," said Legg, who grew up in the parish during the Strange years. "He told us we could have a magnificent church, but we'd have to raise the money in pennies, nickels and dimes."

And they did. When construction was completed, the cutting edge, state-of-the-art church was paid for.

Advertisement

But true of any building, the cost of maintenance never ends. To help preserve the church and other campus structures built between 1919 and 1972, the parish sent a team from St. Rita to attend the Indiana Landmarks' Sacred Places workshops in 2019-20.

Sr. Gail Trippett, a Sister of St. Joseph of Carondelet, who was then parish life coordinator and now an assistant on the parish's preservation and grant projects, describes the workshops as "a yearlong process of teaching congregations about development, looking at facilities, looking at how to repurpose or reenergize them. They did a facilities assessment of our buildings and looked at value-assessing ways we can reach out and help in the community."

After attending the workshops, Trippett applied for and received four grants for the parish totaling $41,000 from Indiana Landmarks. By now familiar with the structures on St. Rita's campus, Indiana Landmarks urged the parish to apply for a National Fund for Sacred Places grant to help restore its bell tower — a $450,000 project.

The organization offers matching grants to select congregations that "contribute significant value to their communities" and whose "historic and cultural significance are essential parts of our national heritage," according to the fund's website.

A new grant team consisting of Trippett, Legg and parishioner Linda Johnson took Indiana Landmark's advice and applied for the grant. Out of more than 360 applicants nationwide, St. Rita was one of only 30 to qualify.

If the parish raises $300,000 by October 2024, the grant will contribute the remaining $150,000 to restore the bell tower.

The facilities assessment found other causes for concern as well. "The church needs tuckpointing and weatherproofing," Trippett told The Criterion. "We need to renovate the Fr. Bernard Strange Family Life Center, upgrade the electricity and heat in the entire building. And the old preschool will need to be demolished" due to significant water damage, mold and mildew. The parish hopes to erect a small museum in its place.

The combined cost of these projects is about $1.15 million. Hence, St. Rita's ongoing grant-seeking efforts. In January, the parish received a $100,000 Preserving Black Churches Grant through the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

"We were thrilled to be awarded," said Legg.

The church is so notable in art and architecture that Indiana Landmarks included it on its holiday church tour last December.

"It's one of those hidden gems that nobody knows about," said Suzanne Stanis, Indiana Landmarks' vice president of education.

Her co-worker Eunice Trotter agrees. "We have this desire to help support the preservation of iconic facilities such as St. Rita Catholic Church," said Trotter, director of Indiana Landmarks' Black Heritage Preservation Program. "There is this wonderful heritage there that we have a responsibility to preserve."

Stained glass is seen in St. Rita Catholic Church in Indianapolis March 5. (CNS/Courtesy of National Fund for Sacred Places/Caleb Legg)

To help preserve that legacy, Legg undertook the arduous task of applying for the St. Rita campus to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

"It's a long process," he said, and the final announcement will be made in 2024.

According to the National Register's website, the listing "is an honorific and does not come with any restrictions as to what can be done to the property by its owners." Being listed makes the property eligible for other grants, too.

Raising funds, applying for grants and seeking National Register of Historic Places status is about so much more than the upkeep of buildings, said Trippett. "Our main purpose is to give us a worship space and space to continue our mission in spreading the good news, to really play a prominent part and be a positive force in the changes that happen in the community and neighborhood around us."