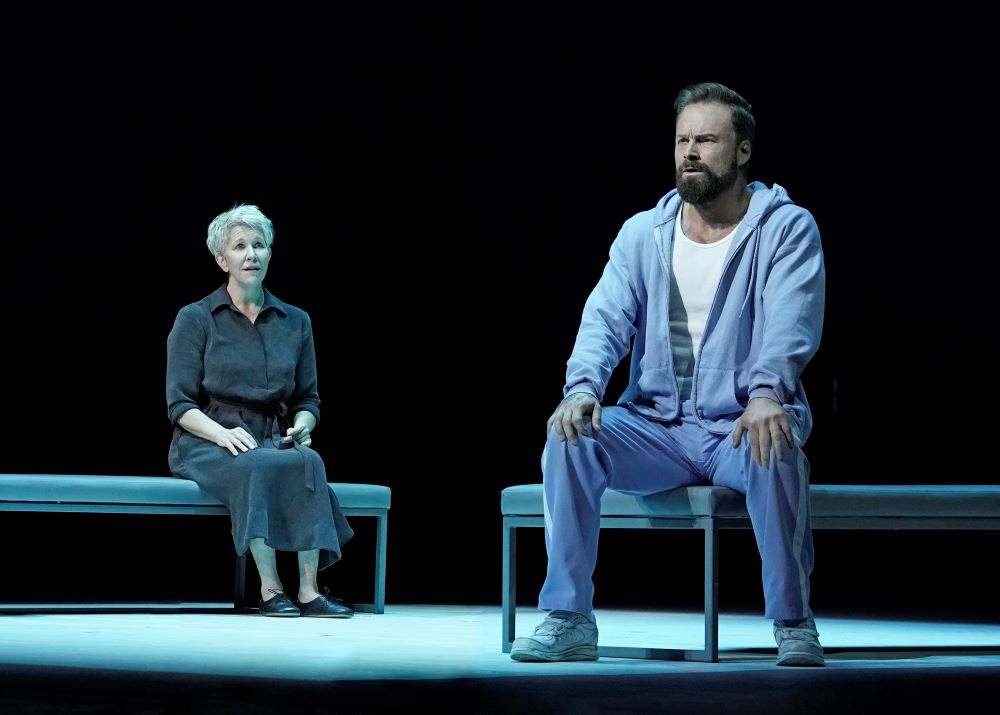

Ryan McKinny portrays inmate Joseph De Rocher and Joyce DiDonato portrays Sr. Helen Prejean in Jake Heggie's "Dead Man Walking." The opera made its Met debut Sept. 26.(Met Opera/Karen Almond)

It was hardly a surprise that the cast members of the opera "Dead Man Walking" were greeted with warm, even passionate applause and bravos at the conclusion of the work's recent first-ever performance at New York City's Metropolitan Opera.

With rapt attention, the audience in the 3,850-seat house had just experienced what is often described as the most popular and performed of contemporary operas — a work that depicts the spiritual journey of Sister of St. Joseph Helen Prejean as she navigates the pain and redemption of death row ministry.

But a particularly poignant moment came when the 84-year-old Prejean — the author of the 1993 memoir on which the opera and a 1995 Academy Award-winning film were based — joined the cast and the opera's composer, Jake Heggie, on stage at the Sept. 26 premiere for their bows.

Prejean's appearance elicited perhaps the evening's loudest applause.

Sr. Helen Prejean speaks at a Sept. 22 public event on the opera "Dead Man Walking," based on her best-selling memoir, sponsored by the Fordham Center on Religion and Culture and held at St. Paul the Apostle Church in Manhattan. (Fordham University/Jim Anness)

Asked later about that tribute and what it is like to see one's life and spiritual experiences depicted on the stage of the nation's largest and most prominent opera house, Prejean characteristically demurred.

"The story is bigger than my life," she said in an interview with Global Sisters Report. "I'm just the prism." The two-and-a-half hour opera "is to make visible what is invisible. My job is to be a servant of the story."

What is "invisible made visible" is redemption — redemption by death row inmate Joseph De Rocher, in acknowledging his role in the murders of two victims (one of whom he also raped) and for which he has been sentenced to die. (The character of De Rocher is a composite of two real people.)

But the circle of redemption is even wider as the character Sister Helen — acting as the convict's spiritual adviser — counsels De Rocher and affirms his humanity. That makes the opera's climatic apotheosis of a nearly-silent depiction of De Rocher's execution by lethal injection while strapped to a gurney all the more poignant and tragic.

Joyce DiDonato portrays Sr. Helen Prejean, and Ryan McKinny portrays inmate Joseph De Rocher in Jake Heggie's "Dead Man Walking." (Met Opera/Karen Almond)

The blossoming of the relationship between the two lead characters is unsteady at first, with Sister Helen uncertain and even frightened at finding herself in the hardened environs of a Louisiana penitentiary while De Rocher remains tightly defensive emotionally.

Yet the depiction of their growing understanding, even friendship, is one of the marvels of the opera, as is Sister Helen's spiritual awakening — a sometimes uneasy, rocky journey. In real life, that journey eventually led Prejean to become one of the nation's most prominent advocates against the death penalty.

The opera, premiered in 2000 and described by the Met as Heggie's masterpiece, is also grounded in an acclaimed libretto by the late Terrence McNally. It is conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin, the Met's music director, and concludes its nine-performance run with a national live performance on Oct. 21. It is one of several contemporary operas the Met is presenting this season in broadening the company's repertory and hoping to reach a younger audience.

Depicting a Catholic sister's evolution as a social justice champion may seem like an unlikely subject for an opera, but like many established operas, "Dead Man Walking" is based on a real historical narrative.

In an interview with the Met Opera, Prejean said that "For a long time, I was doing what you'd call regular nun stuff — teaching children, working with prayer groups, leading Bible studies. I thought the Christian life was just about charity, being kind to people."

'It was and is a deeply human, timely and timeless story that is deeply American but also very universal.'

—Jake Heggie

But as she told the Met and remarked in several public appearances in New York before the opera's Met premiere, "sneaky Jesus" intervened — and her awakening began.

"I heard a sister speak about social justice and the integral connection between being a follower of Jesus and being a person who worked for justice," she told the Met.

Eventually, Prejean found herself writing to a prisoner on death row. "I had no idea I was going to end up being in the execution chamber," she recalled.

So, it was altogether fitting, and unsurprising, that two days after the Met premiere, Prejean spoke to GSR by telephone as she and the cast were traveling on a bus bound for New York's Sing Sing Correctional Facility, north of New York City, to perform excerpts from the opera in front of prisoners and with a chorus of participating inmates.

Advertisement

Prejean narrated the performance, something she was honored to do, saying she was "absolutely touched by the close encounter with the men and the beauty of their voices."

"It was incredible witnessing what they were producing," Prejean said in a follow-up email, "and seeing their creative potential bloom in front of my eyes as persons others deem 'disposable' and beyond redemption. What a privilege to be there and part of it all."

A journey that affirms humanity

Prejean is no stranger to prisons, of course — but neither are members of the cast, whose day at Sing Sing was part of a collective volunteer effort.

Bass-baritone Ryan McKinny, who portrays Joseph De Rocher and mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato, who sings the role of Sister Helen, have both championed prison outreach programs.

DiDonato told GSR she first went to Sing Sing in 2015, "and have been going once or twice a year every year since, except for [during] COVID. It has been the most incredible work of my life." The singer's activism stems from her long involvement in singing the part of Sister Helen, she said, noting her "first encounter with this story changed me, and continues to transform me."

Meanwhile, McKinny exchanged letters with and befriended Texas death row inmate Terence Andrus, who tragically committed suicide in January after the U.S. Supreme Court refused to review his case for the second time.

"He's been on my mind since I've worked on the piece," McKinny said of his preparation for the role at the Met. It was painful hearing of Andrus' death, McKinny said, as he had visited Andrus twice and was planning to see him a third time.

Though McKinny opposes the death penalty, he does not believe the opera champions an explicit position on the question. Rather, the piece is more concerned with the kind of dynamics McKinny learned in his experience with Andrus — to see those on death row and in prison generally as human beings deserving love and respect.

" 'Dead Man Walking' asks you to go on this journey with Sister Helen," he said, "and to see him (De Rocher) as another human being."

In that spirit, McKinny said the day at Sing Sing was both "wonderful and intense," with the audience of inmates reacting differently to the opera and his character than the Met's audience.

"The audience at the Met doesn't identify with my character," he said, something he can feel almost immediately as a performer onstage. But, by contrast, he said, the prison audience "identified immediately with Joseph."

"They had an audible reaction," McKinny said of the Sing Sing inmates, adding that a number of prisoners came up to him afterwards and said, " 'That was so real.' "

"Dead Man walking" is nothing if not real — something evinced both in watching the opera and in public discussions Prejean had in New York with cast members before the Met premiere.

One topic addressed at a Sept. 22 public event sponsored by the Fordham Center on Religion and Culture was Prejean's admission — evident in the opera — that in her initial counsel of a death row inmate, she "didn't know (at first) what to do with the victims' families," acknowledging her misstep.

The opera depicts the families' hostility toward Sister Helen, though by the end of the opera, one family member expresses doubts that the looming execution will ease his pain.

Still, the experience points to the recognition and need for change, both collectively and individually. "The gospel of Jesus is always about change," Prejean said, adding that hope comes with change and possible redemption.

Hope comes through in the opera's libretto but is also conveyed by Heggie's approachable and often lyrical score — something Prejean mentioned at the Fordham event, which was held at St. Paul the Apostle Church, about a five-minute walk from the Met.

Ryan McKinny portrays inmate Joseph De Rocher, Joyce DiDonato portrays Sr. Helen Prejean, and Raymond Aceto portrays warden George Benton in Jake Heggie's "Dead Man Walking." (Met Opera/Karen Almond)

Prejean's remarks at the Fordham forum were similar to what she said in the Met interview. When Heggie called her about doing an opera based on her acclaimed best-selling memoir, Prejean said she told the composer, "I don't know boo scat about opera. Just make me two promises: One, it can't be atonal (a reference to a modern style of composition that often eschews lyricism). We've got to have melodies that people can hum. And two, redemption has to be at the heart of the story. And he said, 'You got it.' "

Prejean calls the opera an example of music and art being the way to bring "the word" of the story to wider audiences. "Art is the way to do it," she told GSR.

A timely and timeless story

That aligns with the composer's thoughts and vision. In an interview, Heggie spoke of the many layers and challenges of writing an opera with spiritual and religious dimensions.

Told that one reviewer of a 2019 performance in Chicago described "Dead Man Walking" as the most Catholic opera since French composer Francis Poulenc's "Dialogues of the Carmelites" — a 1956 work about a group of martyred Carmelite sisters — Heggie said he was drawn to Prejean's story not because she is a Catholic sister "but because she experienced something very human."

"It was and is a deeply human, timely and timeless story that is deeply American but also very universal," said Heggie, whose Presbyterian family attended church only at Christmas and Easter.

Composer Jake Heggie, left, and Sr. Helen Prejean speak at a Sept. 22 event on the opera "Dead Man Walking," sponsored by the Fordham Center on Religion and Culture and held at St. Paul the Apostle Church in Manhattan. (Fordham University/Jim Anness)

"If that reads as Catholic opera, so be it," he said, though Heggie adds writing such a piece was not his conscious intent. "That was not on my mind when I wrote it. I was drawn to the story because it expressed a deeply human journey."

Heggie said his own spiritual grounding is in music itself, noting that the creative "zone" in composition is a strange, even elusive place. "There is something very special and sacred about that space," he said. "You have to honor that."

Though the libretto and the music were created in the wake of the much-lauded film, Heggie said neither he nor McNally sought to put "the movie on stage. That wouldn't make sense."

"The power of the movie and the power of the opera are two different things."

In whatever way a listener approaches the "Dead Man Walking" — as Catholic, humanistic or as something altogether different — there is no doubt that performing the opera can be not only meaningful but transformative.

Moderator David Gibson, far left, joins mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato, who sings the role of Sister Helen, composer Jake Heggie and Sr. Helen Prejean at a Sept. 22 event on the opera "Dead Man Walking/" The forum was sponsored by the Fordham Center on Religion and Culture and held at St. Paul the Apostle Church in Manhattan. (Fordham University/Jim Anness)

At the public forums prior to the Met premiere, Heggie, McKinny, Prejean and DiDonato, who also sang the role at its 2002 New York premiere at the New York City Opera, spoke of the camaraderie and fellowship they have experienced together.

That's not surprising. "It's not the kind of piece where you can just show up and do your job," McKinny said in his interview, calling the role both demanding physically and emotionally.

DiDonato, who grew up in what she described as a "strong Catholic family," was educated at Catholic schools and had both men and women religious in her family. Her uncle, Fr. Edward Flaherty, died in June at age 104 and at the time was the world's oldest living Jesuit. Meanwhile, DiDonato's aunt, Sr. Rita Flaherty, was a member of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet, and died in 2017 at age 98.

"Vocation was a big word around the dinner table," DiDonato said, "and it has always been a kind of compass in my life."

Sister Helen "arrives at a place of deep love"

What strikes DiDonato most about the opera, she said at the Fordham event, "is the truth of it all."

"She arrives at a place of deep love, and she never gets derailed," DiDonato says of her character, though she praises the opera for depicting Sister Helen's very human "stumbles."

Sr. Helen Prejean greets an attendee after a Sept. 22 public event on the opera "Dead Man Walking," based on her best-selling memoir, sponsored by the Fordham Center on Religion and Culture and held at St. Paul the Apostle Church in Manhattan. (Fordham University/Jim Anness)

Heggie and the cast members praise Prejean's honesty, saying it draws them closer to her.

"Sister Helen says 'I'm sorry' all the time, and that makes it easier for the audience to walk with her on the journey," he said. "If she were 'holier than thou,' she'd be less interesting."

In consulting with Prejean during the creative process, Heggie said, "She was my buddy all the way through."

Despite the opera's somber theme, McKinny said of Prejean: "She's just full of joy and is so funny. To see how she moves in the world, that is very inspiring. She meets people where they are."

She does — as in warmly and patiently greeting a long line of well-wishers after the Fordham event.

At that forum, Prejean praised Pope Francis for the 2018 change in the Catholic Catechism, which now states that "the death penalty is inadmissible because it is an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person."

Prejean also notes that the number of executions in the United States has declined in recent years, as has public support for the death penalty. "It's all about heart and minds," she said of shifting public reaction. "There are good people in this country."

Even so, executions are still carried out: Earlier this month, Florida executed convicted murderer Michael Duane Zack, the sixth inmate the state put to death this year.

The curtain call closes the Met premiere of Jake Heggie's "Dead Man Walking," which opened the Met's 2023-24 season on Sept. 26. Sr. Helen Prejean is at the center. (Met Opera/Karen Almond)

The persistence of the death penalty is why Krisanne Vaillancourt Murphy, the director of the Washington-based advocacy group Catholic Mobilizing Network, attended the Fordham event, handing out literature to interested attendees. (A sticker read: "Who Would Jesus Execute?") She also attended the opera.

"Sr. Helen Prejean's life's work, to tell others about the inhumanity and immorality of the death penalty, is a national treasure," Vaillancourt Murphy said in an email. "The Met's 'Dead Man Walking,' especially at this moment, penetrates the American soul and pricks its conscience about how this country has yet to dismantle a cruel system of capital punishment."

Prejean says her activism is not only part of a larger narrative about justice, but also about being a Catholic sister — something the opera subtly notes in Sister Helen's sometimes-difficult relationship with the penitentiary chaplain.

"When you have sisterhood behind you, you have a certain freedom," Prejean told GSR. "Sisters have a freedom to live the Gospel."