(Unsplash/Channel 82)

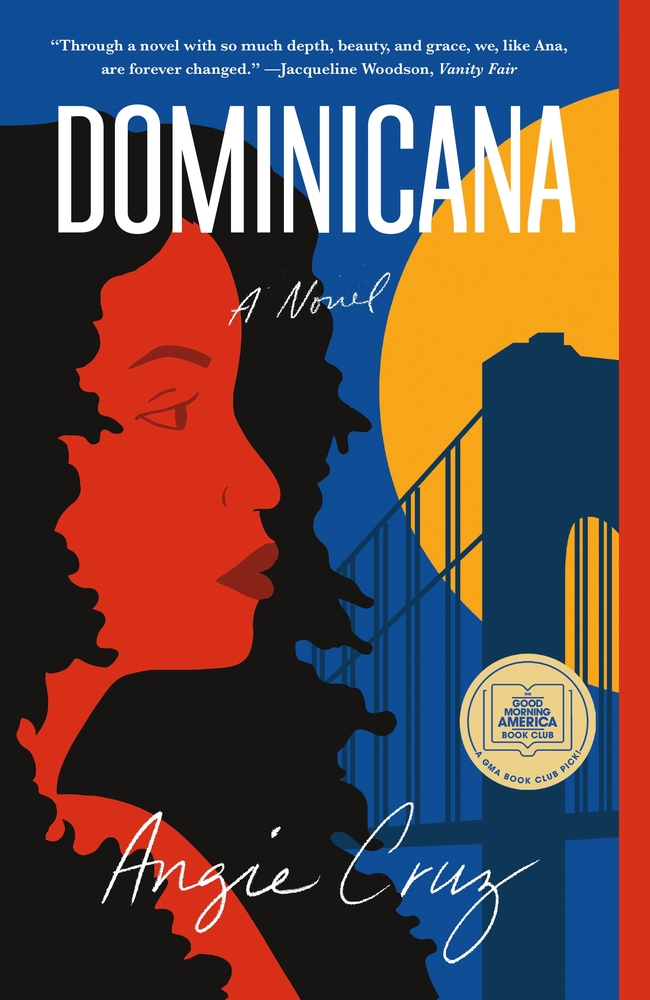

Washington Heights-born author Angie Cruz has been garnering attention for her 2019 New York Times bestselling novel, Dominicana, which has been recently translated into Spanish. Though a work of fiction, the plot is loosely based on Cruz's mother's journey from the Dominican countryside during the late stages of the Trujillo regime to Washington Heights, New York City.

Though there are only a few momentary references to Catholic images and practices throughout the novel, the plot as a whole is rife with spiritual and theological depth.

Ana, the protagonist, is a 15-year-old growing up in Guayacanes, Dominican Republic. She enjoys a simple life on her family's farm, soaking up the mystery and intricacies of the world around her, from the plants and animals to the clothing, words and facial expressions of her family members. Ana's narration alludes to her receptivity and capacity to observe and be impressed by the happenings occurring around her.

We begin to find that Ana's meek and childlike qualities are not obstacles to be overcome, but instead are the means through which she discovers her voice and agency. This paradoxical celebration of vulnerability as strength echoes Christ's words in Matthew 18 about the childlike at heart being welcomed into the heavenly kingdom. Further, Ana's sense of wonder when engaging with mundane realities echoes the sacramental imagination of Catholicism, in which the flesh and material world are understood as gifts, or signs that point us to the Creator-who-became-flesh.

(Unsplash/Thomas Vitali)

Thus the most humdrum, or even painful, everyday realities can contain within them a glint of hope and meaning.

Ana's joyful savoring of the small details is stifled by her marriage to Juan Ruiz, arranged by her parents against her will for the sake of her family's financial security. Juan, part of a wealthy family of restaurateurs, agrees to buy part of her family's farm, and once he and Ana get their feet on the ground in New York, promises to send over for the rest of the family.

Juan, more than twice her age, oscillates between salacious lech and childlike bully. His sexual and physical violence toward Ana is interspersed with moments of contrived tenderness and sentimentality, calling her "mi pajarito," and proclaiming how much he loves her and how much he has done for her.

Cruz's writing imbues Ana's observations of the simplest and most mundane of sights with a sense of depth and fullness.

Everything she sees draws her attention, fascinates her and pierces her heart.

Juan is forced to return to the Dominican Republic after the assassination of the infamous dictator Rafael Leónidas Trujillo to protect his family's restaurants. The political unrest that ensues complicates the process of bringing over Ana's family. But we find that the plot is influenced even more deeply by Trujillo in the character of Juan. Trujillo's lust for murder (of anyone who opposed him) and lust for women is said to have toxified standards of masculinity to epic levels on the island.

Juan's prolonged "business" ventures provide Ana the much needed space to breathe from his abuse. And it is in these spaces that Ana's creative genius and quiet strength emerge. Ana maintains her childlike gaze toward the world as she first sets her eyes on her new neighborhood in Washington Heights. She is filled with awe and wonder in front of the newness of it all, making it so that even being dragged away from her family and homeland with a man who has little interest in her happiness somehow becomes a scintillating adventure. Cruz's writing imbues Ana's observations of the simplest and most mundane of sights with a sense of depth and fullness. Everything she sees draws her attention, fascinates her and pierces her heart.

We find Ana most captivated by the gaze of a nun, Sister Marta Lucía, who teaches free English as a second language classes at the St. Rosa of Lima parish across the street from her apartment. She first sees the nun and her fellow sisters as they lead the parish's schoolchildren around the block. "What a simple life they lead," she thinks to herself, "with God at their beck and call."

Advertisement

One afternoon when Juan isn't home, Ana wanders into the rectory to inquire about learning "Inglis." "The nun's skin glows and her eyes brighten. Welcome! Yes, here we learn English." Ana finds in Marta Lucía a kindred spirit — her receptivity and unconditional hospitality are reflected in the sister's embrace.

"To learn a language is to learn a culture, she says, and learning a language requires interaction." For the sister, teaching is an experience that fosters community. She often takes the class out for trips to the local park and lets them take turns on the swings while practicing verb tenses.

Sister Lucía turns the smallest (or even gravest) of occurrences into a meaningful event. After the police shoot an innocent man outside the Audubon Ballroom and riots ensue, Ana finds Lucía inside the church. "When Sister Lucía finishes praying she holds my hand and frowns...Go home while it's still quiet outside, she says in Spanish. It makes me so happy to hear her speak Spanish...Go home, Ana. And lock your door."

This encounter with Sister Lucia, a woman whose life is consecrated to the God-who-entered-the-flesh, opens the door for Ana to begin to perceive that her neediness and sensitivity to details are not weaknesses. Rather, they are the stepping stones that allow her to experience the world around her more profoundly.

(Unsplash/Grant Whitty)

One day before class she walks toward the bathroom and finds on the way a bag filled with unconsecrated Communion wafers. "Jesus's body! I pick one bag up and press it against my nose." Hearing the sister's footsteps, she hurriedly stuffs it into her bag, praying that the nun won't find out that she "stole Jesus." Upon her return home she pulls out the bag of wafers. "I place Jesus in my mouth and let him melt on my tongue. I eat one piece after another. Maybe he can protect me from the inside, maybe now he can't ignore me like he did the day I asked him to bring back Marisela. I lie back on the sofa and breathe softly because I don't want to throw him up. Jesus, bless my baby." (Marisela is a fellow immigrant from the Dominican Republic and the first guest Ana hosts in her New York home.)

Ana's religious sensibility is colored by her childlike neediness and even by her deviousness. She reminisces about a relative in the Dominican Republic who became a strict born-again evangelical. Her moralistic rules and blind confidence were unattractive to Ana and quite irrelevant to her experience. Instead, Ana is captured by the sacramental imagination of the people at St. Rose of Lima parish, namely Sister Marta Lucía and her virginal gaze toward life, but also by the liturgy.

Ana begins to crave more of this sacramental experience of the mundane when she decides to head off to Mass one Sunday. "Where do you think you're going? Juan calls out to me. To Church, I say. We aren't heathens. We believe in God. Back home, to go to church was a trip, only for the holidays. But in New York City it's just down the street. I've waited long enough."

On the way in she sees her downstairs neighbor, Rose, who grabs Ana by the arm and directs her to sit next to her. "I breathe in the frankincense and appreciate the people's calm, listening to the sound of the organ, the singing choir. The benches wobble and creak when the people stand, sit, kneel. I follow." She prays for her baby, her family, for God to bring her back Marisela.

The story testifies to the faith, hope and determination of the numerous real-life Dominicans, especially Dominican women, who made a new home for themselves in spaces that weren't exactly hospitable to them.

"So. What does God have to say?" Juan asks her. "That betrayers don't deserve forgiveness, I say flatly...In his mind, God is for the unlucky, the poor, and the desperate. Juan thinks he is none of these things."

Dominicana is an ode to the "feminine genius." Through her receptivity and neediness, her attentiveness to small, seemingly meaningless details, Ana finds beauty in the mundane and hope within pain. And it is within the sacramental landscape that Cruz paints that such qualities are upheld as sources of strength to be celebrated, rather than limitations to be scorned. Ana shows us that it's the seemingly small people with big hearts that "inherit the kingdom," and find where true fulfillment lies in life.

In addition to its spiritual significance, Dominicana can serve as a useful resource for those looking to learn more about Dominican history. Before writing the novel, Cruz spent over a year researching archives in the Dominican Republic on the Trujillato and the migration of Dominicans to the U.S. The story testifies to the faith, hope and determination of the numerous real-life Dominicans, especially Dominican women, who made a new home for themselves in spaces that weren't exactly hospitable to them.