A crucifix featuring Jesus with African features is seen at Assumption Catholic Church in Washington. (CNS/Catholic Standard/Jaclyn Lippelmann)

Augustus Tolton was born a slave in 1854 in Missouri, where he was baptized a Catholic. In the Civil War, he fled to the free state of Illinois.

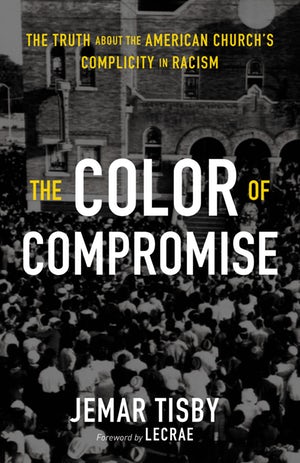

As a teenager there, Tolton believed he had been called to become a priest. But in Jemar Tisby's important new book, The Color of Compromise: The Truth About the American Church's Complicity in Racism, Tisby, president of The Witness, a black Christian collective, writes that "no Catholic seminary in the country would accept a black student."

Fr. Augustus Tolton (CNS/Courtesy of Archdiocese of Chicago Archives and Records Center)

That racist policy forced Tolton to work for 10 years to acquire enough money to attend seminary in Rome. Eventually, in 1886, Tolton became what Tisby calls "the first person of known African descent to become a Roman Catholic priest in the United States," serving mostly in Chicago.

Tisby's account of American Christianity's frequent moral compromises with racism focuses mostly on Protestants, but the disheartening story he tells is broad enough to include other branches of the faith, too, including Catholicism.

Christianity's record on racism in the United States is dismal — and despite considerable progress, it's a record that is still being written, as is an inspiring record of feeding the hungry, housing the homeless, guiding children and adults into a healthy relationship with God and more. Tisby is careful to acknowledge that part of the story. His focus, however, is on American Christianity's many racial failures as well as on his ideas about what can be done now to fix things.

Christianity brought to the New World the possibility of a new start that would reject the crude, monochromatic orthodoxy of white supremacy. But it quickly chose a destructive path that would find many of its followers using the Bible to justify slavery. Tisby takes readers back to those troubling early choices and, from there, recounts the compromises and racist policies that would oppress blacks and other racial minorities until today.

In 250 pages (including notes), Tisby can't cover every racist act that American Christians have committed, but he still manages to tell many stories, beginning with a 1667 law enacted by the Virginia General Assembly, that said baptizing a slave as a Christian does not result in that slave's freedom. Here's what the assembly said: "Masters, freed from this doubt, may more carefully endeavor the propagation of Christianity by permitting children, though slaves, or those of greater growth if capable, to be admitted to that sacrament."

Advertisement

In other words, the Virginians went against the practice in England that forbid Christians from enslaving one another. The New World residents made their evil choice mostly for economic reasons, but, like much of what was to follow, the result was an affirmation of white supremacy approved by the church.

One of American Christian history's great ironies is that the same religion claimed by white supremacists from the earliest colonial days to the fatal 2017 white nationalist protest march in Charlottesville, Virginia, also produced abolitionists and inspired civil rights leaders. Indeed, American Christianity in some ways has been bipolar.

But Tisby wants to be sure that readers get deep into the weeds of the racism with which many individual Christians and ecclesial bodies compromised. It's a story Christians must know in some depth if they ever hope to move beyond their stained history to work toward something resembling what the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. called the "beloved community."

But there's much work to do to get to that happy place. As Tisby writes, "The failure of many Christians in the South and across the nation to decisively oppose the racism in their families, communities and even their own churches provided fertile soil for the seeds of hatred to grow." It all amounts to what he calls "the American church's sickening record of supporting racism."

Given that churches today, as Tisby notes, "remain largely segregated," what can be done to redeem the time? His answer is for Christians to become more aware of the reality of a compromised church, develop relationships with people of races other than their own, and commit to working for reconciliation both individually and as a faith community.

He gets more specific: Learn what people really mean when they call for "reparations" to be paid to people whose ancestors were enslaved. Remove Confederate monuments, or relocate them to a museum setting where their history can be interpreted. Understand what is meant by black theology, and learn from the black church.

In the end, this is a prophetic book that needs to be shared across our racially scarred nation.

[Bill Tammeus' latest book is The Value of Doubt: Why Unanswered Questions, Not Unquestioned Answers, Build Faith.]

Editor's note: To keep up with our latest book reviews, go here to sign up for the NCR Book Club email newsletter.