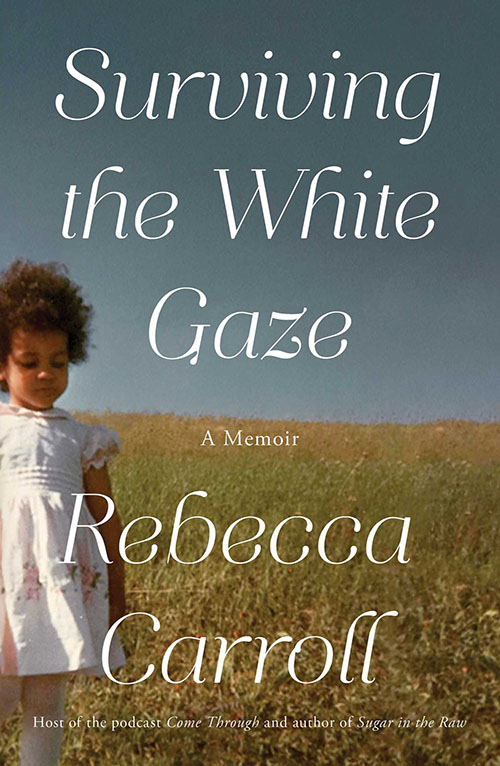

Rebecca Carroll, author of "Surviving the White Gaze" (©Laura Fuchs)

What is it like to grow up Black in a completely white environment? How does a child develop an awareness of herself as a Black woman when she has no experience of being or being seen as Black, living as Black, nurtured as Black? This is Rebecca Carroll's world.

In her new memoir, Surviving the White Gaze, Carroll describes her adoption into a hippie family of white artists with two biological children of their own, who believe in zero population growth. Rebecca is raised as no different from her white parents or brother and sister. She lives in rural, small-town New Hampshire, where she is the only Black child in her school and everywhere else.

The fact that she is clearly Black is seen as irrelevant by her family but not, unfortunately, by those with whom she interacts daily. It is not until she is 6 that she meets someone who looks like her, a Black ballet teacher who lives in a town 15 minutes away.

For five years, she has the joy and confusion of seeing and associating with someone whom she resembles but to whom she does not belong. Her parents are artists, kind and loving, but completely clueless and uninterested in Black life and culture and seemingly uncaring that their adopted daughter is "different" from everyone around her.

A good example of this lack of understanding and care is the condition of her hair, tangled, full of burrs, uncombed, unkempt. She has no idea what to do with it and neither do they but that only seems to upset her not them.

Yet Carroll grows up relatively happy within her family with friends made at school and the freedom to grow and develop into her own person, whoever that might be. Then, at the age of 11, she meets her biological mother, also a white woman. Carroll's father is Black but missing from her life until she is an adult. Her mother, who had her at 16 years of age, constantly denigrates him. He is an apparently weak and addicted person, barely able to care for himself.

Thirsting for a loving and fulfilling relationship with at least her mother, Carroll, instead, slowly begins to realize that her mother is, sadly, a racist, interested only in herself and how she can manipulate and control her. She attempts to regulate her life and, most importantly, her Blackness, leaving her hurt and confused repeatedly.

How do you navigate life when the images of Blackness you have are so few, or embittered, confused or nonexistent? Throughout her teen years, like other girls, she seeks to be loved by the white boys in her life only to discover that they may like her but not enough to go against their parent's disapproval of dating her. Tess, her biological mother, takes her out to adult clubs while still a child, offers her body to a friend and generally acts like anything but a mother. Her teachers are mostly tolerant while having low expectations of her and, as her fifth grade teacher states, she, to her surprise, is beautiful even though she is Black.

What does it mean to be Black, to be a Black woman?

This is the major question in Rebecca's life as she seeks to find herself and her racial identity while somehow maintaining the links and bonds she still has with her adoptive parents and her biological mother. How do you navigate a path that you have never been on? What does it mean to be a Black woman and what difference does/should it make?

Advertisement

The National Association of Black Social Workers in 1972 passed a resolution stating that Black children should never be adopted by white parents because of the trauma that would be inflicted upon the children. Others, I included, understand this but think that being adopted rather than left to linger in foster care or state institutions is also important, with the stipulation that the adopting parents must be willing to learn about and be able to help their child learn about and navigate what it means to be Black in the United States today.

This is becoming increasingly important in light of the increasing number of people who are marrying outside of their usual racial/ethnic boundaries and having biracial or transracial children.

This type of support and understanding Carroll never truly had as a child growing up. She was expected by her adoptive parents to adapt and survive as an obviously Black girl child in a world of whites. That she somehow managed to do so fairly well is reflective of her strength and abilities, not her parents.

As she grew up, searching and looking for who she was, she somehow managed to develop an understanding of herself as an intelligent, lovely, strong and assertive Black woman who worked out a life for herself respective of both parts of herself, Black and white.

She found a substitute Black family that helped her to grow and mature into a valuable professional as a writer, lecturer and podcaster while eventually marrying and having a Black child of her own, a son. Ironically, however, he too is biracial, as she married a white man, but he is being raised as she should have been, as a Black male with all of the challenges and joys of being Black and male in the United States today.

This book challenges the reader to listen to and, in some ways, experience the pain and sorrow but also the joy of this young woman's perilous but ultimately successful climb to self-awareness, love and belonging.

As I read it, I wondered at her experiences growing up in the bucolic setting of Pumpkin Hill, at her clashes with both whiteness and Blackness as she entered her teens and moved into adulthood and her journey to self-affirming Black womanhood. She speaks of the limitations of feminism, and I urge her to explore the possibilities of womanism, a liberating movement of women of African descent.

Her journey is far from over and she is still caught up in the webs that encompassed her for most of her life. But it is abundantly clear that she will succeed in making of her life what she, not others, will.

Surviving the White Gaze is a painful yet uplifting book to read as you observe Carroll's efforts to discover who and what she is. Her struggles with her birth mother who constantly seems to want to force her into self-denial and hatred of her own Black self; her adoptive parents who love her blackness, yet see it as exotic and feel no need to help her to explore and uncover what exactly it means to be Black in a white environment; and the many others, Black and white, that she encounters as she struggles and fights to win her own place in a world too caught up in race and racism.

Carroll provides insights for us on the pain and difficulty of being Black in an allegedly white nation. Yet, she perseveres and finally succeeds, and we thank God that she does.