An explosion caused by a police munition is seen while supporters of then-President Donald Trump gather in front of the U.S. Capitol Building in Washington on Jan. 6, 2021. (CNS/Reuters/Leah Millis)

Yesterday was the first anniversary of the attack on the U.S. Capitol. That day, Archbishop José Gomez issued a statement condemning the violence, and promising prayers for members of Congress, congressional staff and the police. He added:

The peaceful transition of power is one of the hallmarks of this great nation. In this troubling moment, we must recommit ourselves to the values and principles of our democracy and come together as one nation under God. I entrust all of us to the heart of the Blessed Virgin Mary. May she guide us in the ways of peace, and obtain for us wisdom and the grace of a true patriotism and love of country.

Like most Americans, Gomez recognized how appalling the day's events were and, given the fact that even many Republicans finally broke with the would-be despot still living in the White House at the time, you could almost hear the collective sigh of relief that the chapter of American history marked "Trump" was being closed.

Except it wasn't.

Donald Trump has made the entire Republican Party dance to his ongoing tune of downplaying the attack on the Capitol, denying the legitimacy of President Joe Biden's election and taking steps to put Trump loyalists in key election oversight posts.

Why, then, have the U.S. bishops failed to sound the sense of concern and alarm for the "values and principles of our democracy" that continue to be threatened? Surely the sanctity of the vote is above partisan politics of a kind the bishops are right to shun.

For most of American history, the story of U.S. Catholics was one of trying to prove that we were loyal citizens, confronting the charge that our religion and its precepts made it impossible for us to adhere to the norms of a democratic polity.

Advertisement

From colonial laws that deprived Catholics of basic rights to vote or hold office, through the 19th century's relentless nativism, up until the 1960 election when prominent Protestant pastors like Norman Vincent Peale and liberal organs like The Nation still doubted a Catholic could be trusted with the powers of the presidency, Catholicism was understood to be a threat to democracy.

The charge was not based in mere cotton candy. Official church teaching held that in countries where Catholics were in the majority, Catholicism should become the established religion, with other religions merely tolerated and only insofar as the Catholic majority permitted. On the other hand, if Catholics were in the minority, official church teaching held that Catholics should enjoy full liberty to practice their religion without interference from the government. This double standard was defended by the proposition that error has no rights.

The charge of Catholic anti-democratic prejudices was defeated by two events, one domestic and political, and the other in Rome and ecclesial.

First, Catholic Americans proved themselves to be good citizens, serving in local and federal government in a variety of posts, serving in the military when the country went to war, paying taxes, forming Boy Scout and Girl Scout troops, attending a different church on Sunday morning and disproportionately sending our children to parochial schools, but in most respects behaving in ways little different from our Protestant and Jewish fellow citizens.

In looking back at John F. Kennedy's election, we tend to focus on his speech to the Houston Ministerial Association as the key to his overcoming Protestant prejudices. We do so in large part because the issues entailed in figuring out how a faithful Catholic relates to politics in a pluralistic society are still with us.

President-elect John F. Kennedy shakes hands with Fr. Richard Casey, pastor of Holy Trinity Church, after attending Mass at the church prior to inauguration ceremonies in Washington Jan. 20, 1961. (CNS/Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington)

Just as important as that speech to Kennedy's electoral success was his prior heroism during World War II. The story of PT-109, crushed in two by a Japanese destroyer, and Kennedy's heroic effort to save his crewmates, made headlines around the world in 1943.

Kennedy, the child of privilege with numerous severe physical ailments, used his father's influence to get into the Navy. Compare that with the behavior of Bill Clinton and George W. Bush, who used their connections to get out of serving. John Kennedy's older brother, Joe Jr., had been killed in action during the war when the explosives in a plane he was flying detonated prematurely. He had already flown 25 missions at the time of his last flight, and had the option of returning home. Instead, Joe Jr. volunteered for the top-secret mission that took his life.

In that same Houston speech, Kennedy said:

This is the kind of America I believe in — and this is the kind I fought for in the South Pacific, and the kind my brother died for in Europe. No one suggested then that we may have a "divided loyalty," that we did "not believe in liberty," or that we belonged to a disloyal group that threatened the "freedoms for which our forefathers died."

He dared people to gainsay his patriotism, and Kennedy could point to millions of fellow Catholics who, like him, had served the country in war.

Sixty years later, when the next Catholic became president, no one asked if he could be a good American, even while many asked if he was a good Catholic!

The second nail in the coffin of the anti-Catholic canard that Catholics could not make good Americans came at the Second Vatican Council (1962-65). There the 19th-century hostility to modern liberal democracy was abandoned, and the church officially recognized the value of religious liberty for all people, and voiced support for human rights and democratic norms for all societies. I recently recapitulated some of that history in my column following Biden's summit on democracy last month.

Given this history of patriotic Catholics and the development of doctrine at Vatican II, why have the bishops not been more outspoken in defending democracy?

I understand that they may not wish to go to the mat to champion more hours for early voting. But as Yuval Levin — who is no liberal — recently wrote in The New York Times, there is room for bipartisan consensus about how votes are counted and certified, how "requiring accountability and transparency and setting some boundaries on what can happen after an election" could forestall future electoral shenanigans of the kind Trump tried, and failed, to get election officials to perpetrate last time.

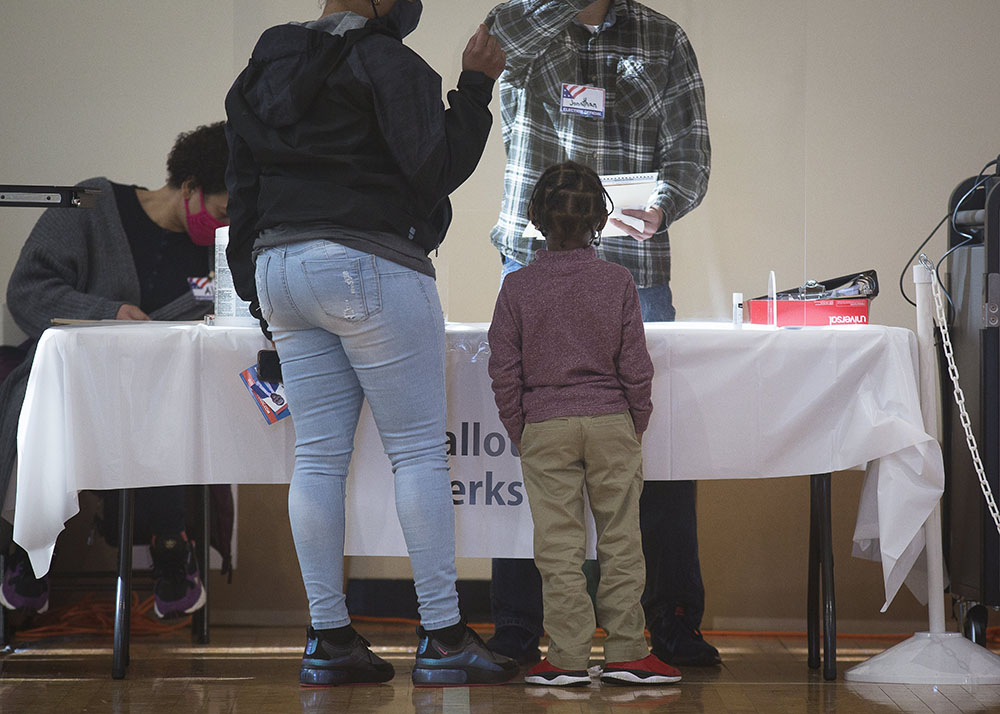

A boy listens to his mom receive instructions on how to vote at Ida B. Wells Middle School in Washington during the presidential election Nov. 3, 2020. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

Additionally, the U.S. bishops have long recognized the importance of the rule of law, even when the law contradicts the teachings of the church. For example, after the U.S. Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage nationwide in 2015, Washington Cardinal Donald Wuerl, one of the best theologians among the bishops, issued a statement that began and ended by recognizing that the ruling was now the law of the land and should be respected as such, even while the law of the church made same-sex sacramental marriages impossible.

The bishops in many states are not viewed as possessing the moral authority their predecessors did, but you would be surprised how influential their voice can be in some state legislatures. In several red and purple states, it was the intervention of Catholic bishops and other religious leaders that frustrated efforts to enact misnamed right-to-work laws that make it harder to organize unions.

Some bishops, and some conservative donors and academics, have demonstrated a hostility to Vatican II. That may explain why some bishops are reluctant to restrict the celebration of the Tridentine rite, or why they staff their seminaries with theologians convinced that the 1950s were a golden age in the life of the church, or why they are quick to quote previous popes and so allergic to citing the incumbent pontiff.

Could it also explain their indifference to the future of democracy? Is reactionary ecclesiology a church a kissin' cousin of reactionary politics? It shouldn't be.

I hope the bishops find their voice and find it before it is too late. History is littered with people who thought they could be bystanders, only to discover they, too, were swept up in the evil they failed to denounce when there was still time.

The bishops of the United States have only to look to the theology of the Second Vatican Council and to the proud traditions of American Catholics to find the inspiration needed to confront these threats to democracy. Those who aspire to moral leadership must do all they can to ensure the tragic assault on democracy of Jan. 6, 2021, will never be allowed to repeat itself.