Atlanta Braves legend Hank Aaron throws the ceremonial first pitch to former manager Bobby Cox April 14, 2017, prior to the first game at SunTrust Park. The longtime home run leader died Jan. 22, 2021. He was 86. (CNS/USA TODAY Sports via Reuters/Brett Davis)

Hank Aaron, who was baseball's home run king for 33 years, overcame racism to make his mark in the game he loved. Aaron died Jan. 22 at age 86.

Aaron, who became a Catholic while playing for the Milwaukee Braves, joined the Baptist faith later in life.

He never hit 50 home runs in a season, much less 60 or even 70 as other sluggers did; in his best season, he knocked 47 homers out of the park in 1971, when he was 37 years old. But it was his consistency that allowed him to amass 755 round-trippers over 23 seasons playing for the Milwaukee and Atlanta Braves, and — after he had set the record — back to Milwaukee to play for the Brewers.

Aaron was not flashy or a self-promoter, either. But he was durable. After his rookie season in 1954, he played at least 150 games a season every year through 1968; this included seven years when the season was just 154 games. When he dipped to 147 games played in 1969, Aaron still socked 44 homers.

He had eight seasons of at least 40 home runs, 15 seasons in which he hit at least 30 — one of only two players to do so in the major leagues' 152-year history, and 19 straight seasons in which "The Hammer" clouted at least 24.

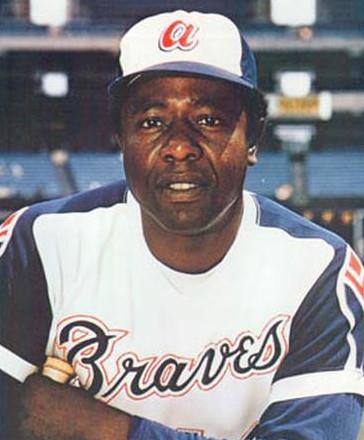

Hank Aaron with the Atlanta Braves in 1974. (Wikimedia Commons)

Aaron and his first wife, Barbara, were received into the Catholic faith in 1959.

According to a Catholic News Service article from that May, they were baptized at St. Benedict the Moor Church in Milwaukee, along with their children, 3-year-old Gayle and 2-year-old Henry Jr. A third child, Larry, was baptized at birth.

"Mrs. Aaron said the Aarons first became interested in joining the church when their twins were born at St. Anthony's Hospital in Milwaukee," the article said. Both Larry and his twin were baptized, but the unnamed twin died.

The Aarons began their "instructions" in Catholicism shortly before Christmas 1958, and completed them when the Braves returned to Milwaukee from spring training, according to the story. "Mrs. Aaron said there are no other Catholics among family relatives," it added.

In a 1991 interview, Aaron credited Fr. Michael Sablica, a priest of the Milwaukee Archdiocese, for helping him grow as a person in the 1950s, when baseball often reflected the prejudice and racism of society, especially that of the South.

"Fr. Sablica and I have been good friends for a very long time," Aaron said. "He taught me what life was all about. But he was more than just a religious friend of mine, he was a friend because he talked as if he was not a priest sometimes. ... He was just good people." The priest was active in the civil rights movement, and encouraged Aaron to be more vocal about the things that he believed in but had yet to speak about publicly.

Aaron was known to frequently read Thomas a Kempis' "The Imitation of Christ," which he kept in his locker. He and Barbara divorced in 1971, and Aaron remarried in 1973.

Born in Mobile, Alabama, Aaron had to confront racism anew when the Braves moved to Atlanta in 1966. The on-field verbal abuse, hate mail and death threats fueled his desire to break Ruth's 714-homer record — he ended the 1973 season with 713, which set up a torrent of abuse in the offseason — but also made him vow not to let home runs be his only business.

"I feel like it's my responsibility to speak out on social issues, because after all, if I had not been a baseball player, I would probably be in the same position as a lot of my Black brothers, and so I feel like it's my obligation to do these things," Aaron said.

Aaron continued to speak out about racism and equity after his playing days ended in 1976.

A right-handed hitter, Aaron played briefly in the Negro Leagues before being signed by the Milwaukee Braves. In his early pro days, he hit cross-handed, meaning he put his left hand above his right when he was holding the bat, before a coach corrected Aaron's swing.

Aaron was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982, the first year he was eligible. In addition to his career home run totals, he led the National League in home runs, runs batted in and doubles four times each, slugging average and runs scored three times each, and batting average and hits twice each.

Advertisement