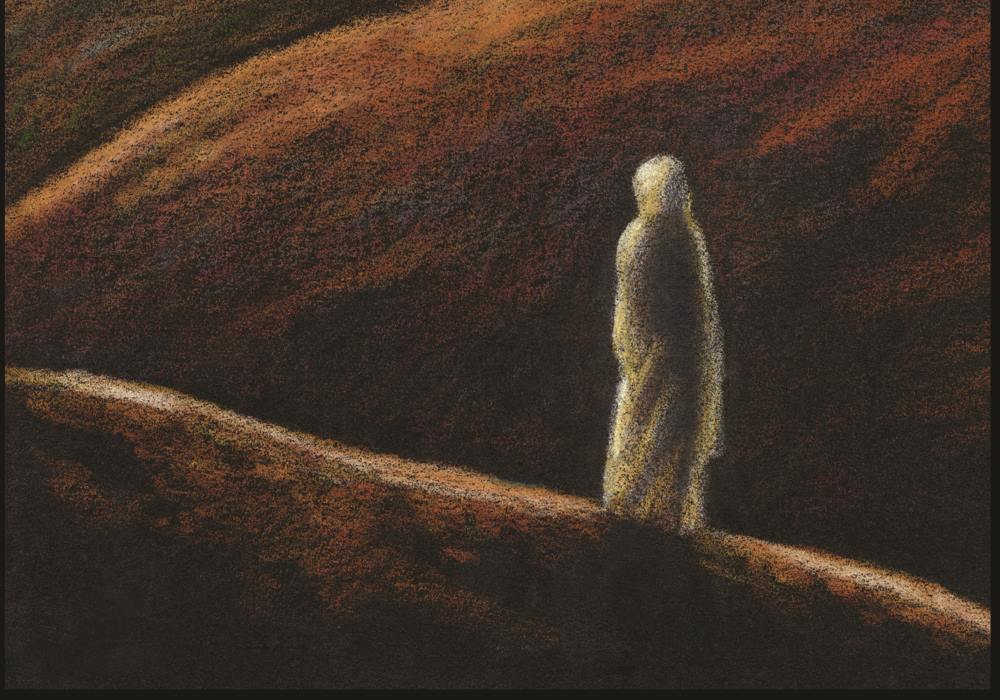

Art by Julie Lonneman

If you want to become whole,

let yourself be partial.

If you want to become straight,

let yourself be crooked.

If you want to become full,

let yourself be empty.

If you want to be reborn,

let yourself die.

If you want to be given everything,

give everything up.

—Lao Tsu, Tao Te Ching*

This meditation from the Tao Te Ching, like many others from Eastern religious traditions, invites spiritual seekers into profound reflection about life as paradox. Lao Tsu challenges prayerful people to consider the revelation that all life is contradictory, and asks us to place ourselves at the center of the mystery of life and death.

The individual soul must find God in what seem to be the great inconsistencies and absurdities of life: This is the invitation of all the great religious traditions. Is this not also where Lent invites us?

God speaks in paradox

A friend from India, a faithful, practicing Hindu, told me why in Eastern art Brahman (God) is always portrayed as a blank surface or a wall with two faces on opposite sides. Such artistic renderings of the divine are meant to show that whenever God speaks in the world, God must speak paradox: Krishna and Shiva.

In art, these Eastern believers attest to the basic truth of all human life — that one word can never capture all truth. Only paradox can capture the mystery of God. When God speaks light, God must also speak darkness; when God speaks creation, God must also speak destruction; when God speaks one, God must also speak many. When God speaks life, God must also speak death.

Lent, our Christian season of preparation for the holiest days of our liturgical year, is a time to enter more deeply into the mystery of the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. Lent is our invitation into the profound spiritual truth expressed by Lao Tsu, Hindu art and theology, and the life of the Messiah. It is our invitation into the heart of Christ, the heart of God, the heart of life and death.

Both-and thinking

In his five-volume study of the development of doctrine in the Christian tradition, the great Lutheran theologian Jaroslav Pelikan (d. 2006) makes a basic distinction between the Protestant and Catholic approaches to doctrinal development.

Pelikan says that Protestantism is intellectually rigorous. It tries rationally to understand and make sense of profound truths. So the Protestant intellectual tradition tends to use either-or language and thinking. For example, either Jesus is fully God or he is fully human. At its best, this rigorous intellectual analysis leads the Protestant theologian to clarity and insight. At its worst, it leads the Protestant theologian to a diminishment of mystery, to a loss of faith, to atheism.

Pelikan argues that Catholic theology, on the other hand, has traditionally preferred both-and thinking. Catholic theologians tend to make doctrinal statements about profound truth by holding the paradox together with the conjunction "and," as in: Jesus is fully God and fully human. When they are challenged with the intellectually rigorous question of how anything can be fully two things at the same time, Catholic theologians are very comfortable in stating that it is a mystery. At its best, this approach to doctrine holds in tension the great paradox that is life itself, and invites practitioners into the heart of truth, into profound silence. At its worst, this position leads to intellectual laziness, sloppy thinking, even idolatry.

‘Lifting up' in John's Gospel

Of the four Gospels, John's Gospel is the one that uses paradoxical language the most directly. John makes it clear that death and resurrection in Jesus are not two events but one: death/resurrection.

Can John be right? Could God really not speak life without speaking death? Did Jesus have to become human not only to save us from our sins, but to begin to break down our fear of death? Might death really be a door, rather than a wall between life and life? (We affirm this in the preface of the funeral Mass: "For the faithful Christian, life is changed, not ended.")

In the prologue to John's Gospel, we read: "Through him all things came into being, and apart from him nothing came to be. Whatever came to be in him found life, life for the light of all people. The light shines in darkness, a darkness that did not overcome it" (John 1:3-5).

Light is light, John seems to be saying, only when it shines in the darkness. How can we see and know the light if we do not see and know the darkness? Life needs its opposites in some strange and mysterious way that will be made clearer in the life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

In Chapter 12 of John's Gospel, we read: "The hour has come for the Son of Man to be glorified. I solemnly assure you, unless a grain of wheat falls to the earth and dies, it remains just a grain of wheat. … What should I say — ‘Father, save me from this hour'? But it was for this hour that I came to this hour. Father, glorify your name! Then a voice came from the sky: ‘I have glorified it, and will glorify it again' " (John 12:23-28).

Glory does not wait to come at the moment of resurrection, in John's understanding. Glory has already occurred and will occur in the fullness of Jesus' life, in his death and in his resurrection. The life and death of Jesus is not separated into two events; this Lent, we contemplate the mystery of its oneness.

In John 17, we read: "Father, the hour has come! Give glory to your Son that your Son may give glory to you. … Do you now, Father, give me glory at your side, a glory I had with you before the world began. … Father, all those you gave me I would have in my company where I am, to see this glory of mine which is your gift to me, because of the love you bore me before the world began" (John. 17:1-5, 24).

The Johannine Jesus tells us that he is being glorified now, in his movement toward suffering and death, even as he was glorified before the world began. How much Jesus wishes we could understand the great gift of the Father that is his glory always — as he slowly approaches the cross, and at his resurrection: one event.

Advertisement

We enter the mystery

John's Jesus knows that for us to be in Christ, to be in God, to know the immense truth that is God's love for us all — we too must enter that mysterious, contradictory and life-giving place that is death/resurrection. "Father, all those you gave me I would have in my company where I am, to see this glory of mine which is your gift to me" (John 17:24). John seems to be saying that this unity among the persons of the Trinity, and unity with Christ, will encompass all of us who believe when we enter into the hour of death/resurrection, our own and that of Christ.

This understanding allows Christians to see the life-giving Spirit of God in life and in death; in light and in darkness; in creation and in destruction; even in what seems absurd and contradictory. In other words, we enter into the fullness of life/death/resurrection with the sure and certain hope that the love of God surrounds us in every moment of our existence. We can see Christ, as Mother Teresa did so well, in the dying eyes of a starving child or in the joy of a laughing child. We can see Christ when we are empty in spirit and when we are full in spirit. We can see Christ in the fullness and abundance of the earth and in its tragic and destructive power. In all things we can see God glorified, not just after the cross but on the cross as well.

The invitation of Lent

This Lent our beloved church in the West is suffering the diminishment of its membership, a dwindling number of clergy and religious, a loss of prestige in the halls of power over the continued impact of the sexual abuse crisis, the disappearance of many young people from our communities. This Lent we struggle to find common ground in our political or ecclesiastical worlds. Many are waiting for a resurrection, a time when clarity and light destroy the confusion and the darkness of our current dying. Then we shall see and know the glory of God again.

The challenge of life, of its stubborn paradox and mystery, of the message of the Christ of John's Gospel, is to see Christ not only in resurrection but also in death on a cross, to see Christ in the dying as well as in the rising. Lent invites us to begin to see the glory of God not only after all the trials and difficulties, pain and suffering, but in them as well.

The moment of the glory of God is in all those moments of dark/light, creation/destruction, death/life that make up our lives and the lives of the people and institutions we cherish. All death/life is giving glory to God. Christ came to have life, and we are invited to have life in its fullness.

Lao Tsu wrote, "If you want to be reborn, let yourself die." Can we begin, this Lent, to see more clearly the glory of God in the contradictory nature of all the experiences of our lives? Might we begin to glimpse the gift that is Jesus' life/death/resurrection — that in the Paschal Mystery, our lives and the lives of all we cherish are being glorified by our heavenly Father?

This is the invitation of Lent. Dare we believe it?

* Lao Tsu, Tao Te Ching. Stephen Mitchell, translator. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1988.

Editor's note: This reflection was originally published in the March 2012 issue of Celebration. Sign up to receive daily Lenten reflections.