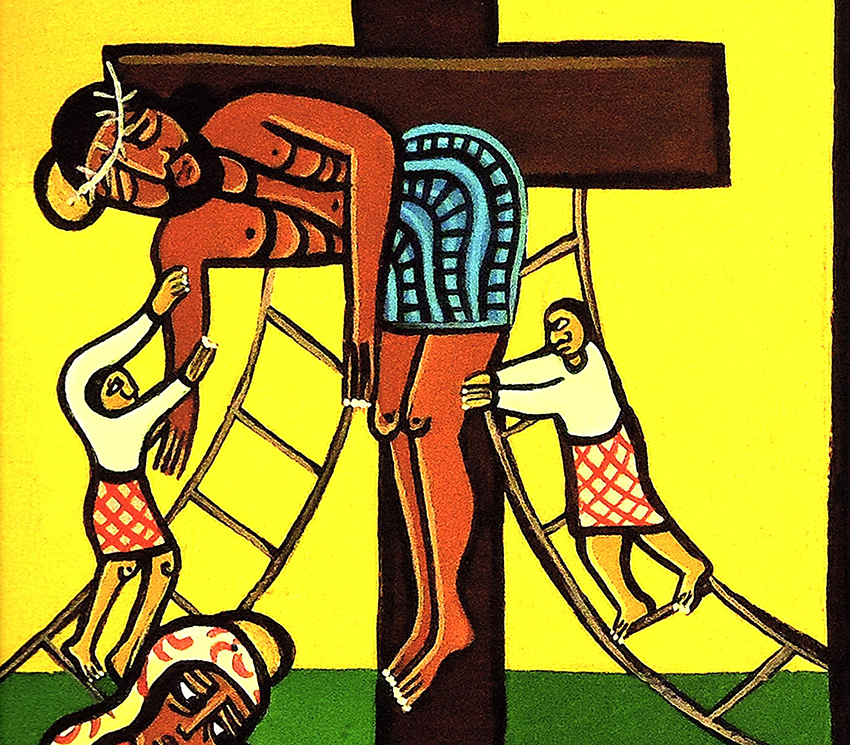

(Laura James)

In the 1950s in some Benedictine communities, a rousing song — locally composed lyrics and tune — welcomed Easter:

Bursting forth from Pharaoh's prison, Alleluia! Let us sing! Alleluia! Christ is risen. Alleluia to our king!

So, speaking of prisons — and our Scriptures often do speak of them by one name or another rather often in this season — I want to tell you about last November when our reading group gathered for several 90-minute discussions of Michelle Alexander's 2012 book, The New Jim Crow.

Jim's back and we never noticed.

The "new" Jim Crow is no longer new. It appeared in U.S. cities and courts more than 30 years ago. Our attention was elsewhere. Now, shamefully late, we must attend to what we missed. Michelle Alexander's book and our discussions bring me to write here for our Lent 2019. Midway through April we keep the Triduum and that is entrance to the 50 days of Easter. The Scriptures assigned to the liturgies of these weeks involve some of the same players and places as The New Jim Crow: police, witnesses, judges, arrests, trials of sorts, imprisonment, state execution, and bystanders like most of us.

Out of the civil rights movement with its hard but positive impact on the U.S. from the late 1950s to the 1970s, came something that might now be seen as a regression. This had many dimensions but was largely concerned with imprisoning vast numbers of black men — quietly, one at a time. It did not directly confront the achievements of the civil rights struggle. But even as more African American women and men gained prominence in government, academics, business and the arts and much else, the majority of the black population found themselves in a world where criminal charges, usually involving drugs, became a major tool of repression in amazing and unchallenged ways. This was the new Jim Crow, the quiet Jim Crow, the Jim Crow who is not in your face unless you were/are black, male and under 40.

We can't tell the whole story without numbers, but numbers only tell a part of it. Alexander writes: "In 1972, fewer than 350,000 people were being held in prisons and jails nationwide, compared with more than two million people today." The following is from The Growth of Incarceration in the United States by The National Research Council of the United States:

The U.S. penal population of 2.2 million adults is the largest in the world. In 2012, close to 25 percent of the world's prisoners were held in American prisons, although the United States accounts for about 5 percent of the world's population. The U.S. rate of incarceration, with nearly 1 of every 100 adults in prison or jail, is 5 to 10 times higher than rates in Western Europe and other democracies.

And from the Population Reference Bureau:

Since 2002, the United States has had the highest incarceration rate in the world. Although prison populations are increasing in some parts of the world, the natural rate of incarceration for countries comparable to the United States tends to stay around 100 prisoners per 100,000 population. The U.S. rate is 500 prisoners per 100,000 population.

But even those numbers don't tell the full story. They must be seen in light of parole and probation systems. When these are included, the numbers more than double the persons under the control of police and prison authorities.

When we know this, shouldn't we ask what has happened that in just three decades, we became a world leader by far in imprisoning our population. How did we do it? One must go to the breakdown by race of the prison, parole and probation populations.

In absolute numbers, however, federal and state prisons in 2011 held more non-Hispanic black (581,000) than non-Hispanic white (516,000) inmates. In 2012, 13 percent of U.S. residents were non-Hispanic blacks, and 63 percent were non-Hispanic whites.

Note that: Sixty-three percent of the U.S. prison population — black. Thirteen percent of the U.S. population — black. Charges related to drugs put most of these folks into prison and into the prison system. Drug use affects about the same proportion of white people as it does black people.

Maybe we thought it was about drugs?

Our reading group found ourselves discussing: How did this happen? Where were we white adults when prison populations, especially the number of African American prisoners, increased beyond anything known in this country before? As young adults, most of us had memories of efforts fixed on rehabilitation and education, on restoring to society those sent to prison. Where did all of that go? If you wonder the same, you might do some late-Lent reading of Michelle Alexander's book. You'll see how the so-called War on Drugs was designed to focus on the black population. Surprised?

For now, let me throw out a few words and phrases that you will likely recognize, phrases not heard 40 years ago and now known to most of us: three strikes sentencing laws, war on drugs, plea bargaining, traffic stops and searches, racial profiling, consent searches, drug forfeiture laws, paramilitary drug raids, mandatory minimum sentences, solitary confinement, stop and frisk, SWAT (Special Weapons and Tactics) teams.

Do you score well on knowing those terms? Do you remember hearing them before 1980? One by one these phrases entered the American vocabulary. Sound pretty harmless? Not so. They made the U.S. the world leader in incarceration and in severe penalties for what are barely misdemeanors elsewhere in the world. Thus we were to accept drug laws geared to the drugs used in black communities, to accept extreme power given to police, to accept pressure to plead guilty because of what might happen if you don't. Result: A new world inhabited by young black men. A new Jim Crow world, separate and unequal.

Other lists would be necessary to deal with penalties after prison time is served. These have to do with being denied employment and housing in ways that may vary from state to state. Thus society extends punishment and keeps this population in great uncertainty and poverty. Paying one's debt to society easily becomes life-long.

The white majority can live our lives without knowing a thing about such matters. And the right to vote? Only two states, Maine and Vermont, allow imprisoned citizens to vote. Felons in other states, even when released, are excluded from voting for various lengths of time, some forever. In the fall 2018 U.S. elections, Florida voters by a large majority restored voting rights to those who had served their sentences. How many would that be? This alone is said to have made over a million citizens in Florida eligible to vote again.

Other ramifications of the never-necessary war on drugs would include how we have, little by little, accepted the militarization of the neighborhood police, the SWAT teams, the equipment that the U.S. Defense Department wants to pass on so they can spend their ever-swelling share of our tax monies on yet more sophisticated equipment.

In these decades, to accommodate the ever-growing prison population, some prisons were turned over to private companies. Prisons now may be run on government contracts with "for profit" companies. And of course profits don't come from humanizing prisons and providing job training and opportunities to study and to learn skills.

Advertisement

I was in jail and you ... weren't!

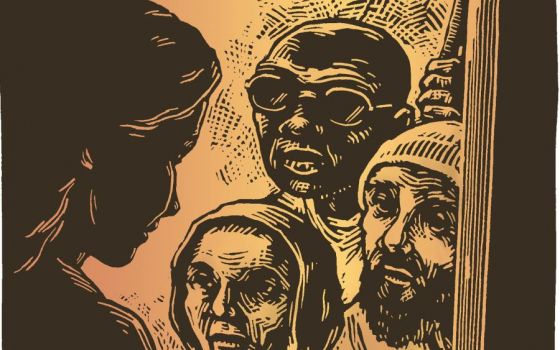

These and other challenges arise from taking time with one book that confronts the reader with a reality many of us have avoided for almost four decades. For those who teach or preach, reflect that in the last days of Lent and the Triduum, this person Jesus who is in trouble with the law isn't "Jesus" to the authorities, the bystanders, his family, even to himself. He's somebody in trouble with the "authorities," in trouble with occupiers, in trouble with the religious authorities. And none of them make this up, he really is challenging authority and siding with the those who have no power.

Part way through one of our discussions of this book, we found ourselves (we're a group of seniors) asking: How did this happen in our adult lives? Where were we as prison populations grew and huge numbers of young black males came under the control of the prison system both in prison and after? We mostly remember efforts a few decades earlier where we wanted a different approach to prisons. Could they educate and restore to society those sent to prison? Where is that now? And when did paying one's "debt to society" become life-long? Should we now be seeking ways for "society" to face the truth?

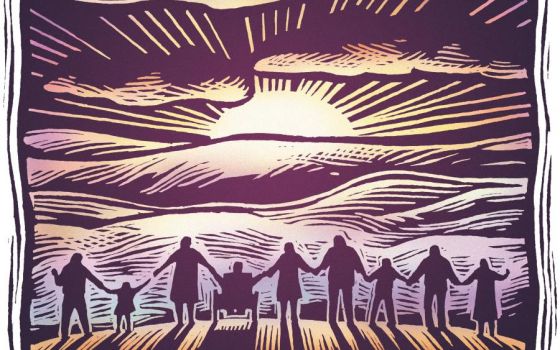

You may have noticed the past few years that something called "restorative justice" is being discussed and sometimes practiced. It may mean a non-prison approach to those accused. It may also mean facing our responsibility for unjust treatment of individuals and families, primarily in the black community, during the last four decades.

What opportunities do most of us have to talk about these matters? How hard it is to face our responsibility given the present complex troubles in our society, troubles that do and will affect us all day by day? How important is it that we make time to read, to study and to converse about them? Can we encourage our churches to ponder the dangers, racist and otherwise, of our legal and penal systems?

In three-plus decades, a vast racist practice has been funded and pushed forward. While we took pride in having a black president, the new Jim Crow kept on making our lives more separate and unequal. So the challenge here, to you and to me, is to ponder, to read, to discuss. Realize how the Scriptures and rites of Lent and Triduum can speak to us about such matters.

What do the deeds of Triduum — the three days between Lent's end and the Easter season — what do they sing and say and do to confront our responsibility in these times? What does down-on-our-knees washing each other's feet mean? What does it mean to ponder, maybe together, the arrest and execution of Jesus and of those two others, then to embrace and kiss the cross which is, after all, a tool of execution? What then does it mean to listen to the long stories and poems of Saturday-turning-to-Sunday? Where in this is the strength to realize this year that we are blessed when we see and take on what is poisoning our times? Maybe that is to be our confrontation with the racism so deep in our time and culture.

What is it to say "Alleluia!" this year? That is exactly what we have to create.

Editor's note: This reflection was originally published in the April 2019 issue of Celebration. Sign up to receive daily Easter reflections.