A service member of the Ukrainian armed forces walks at fighting positions on the line of separation near the rebel-controlled city of Donetsk April 26. (CNS/Reuters/Anastasia Vlasova)

When Russians celebrated their traditional World War II Victory Day on May 9, there were fears of a new upsurge in fighting on Ukraine's eastern border, where more than 100,000 Russian troops are currently deployed.

Although clashes have been only sporadic, people are still dying across the embattled region and anxieties remain high — not least among its scattered Catholic communities.

"People are trying to leave, fearing whole areas could fall under Moscow's control — this conflict has already lasted years, and they simply can't cope with such conditions," Auxiliary Bishop Jan Sobilo of Ukraine's Kharkiv-Zaporizhia Diocese told NCR.

"Even when things seem quieter, there's still great tension, and people no longer have faith that the yearned-for peace will return," said the prelate. "This makes it hard for Catholics to stay — especially if they have some chance of finding work and housing in the west."

Russia began deploying land and airborne divisions in late March in its Rostov, Bryansk and Voronezh border regions, triggering warnings from Western governments and causing Ukraine to take countermoves.

The security alarm is the worst since Crimea's forced April 2014 annexation by Russia sparked a war against Russian-backed separatists in Ukraine's Luhansk and Donetsk regions, which has since left more than 14,000 fighters and civilians dead.

In mid-April, the Ukrainian Council of Churches and Religious Organizations (a grouping of 16 Catholic, Orthodox and Protestant denominations) as well as Jewish and Muslim unions, urged a return to cease-fire agreements, warning that recent shelling and skirmishing had caused "deep grief and human suffering," at a time when Ukrainians had looked to the Orthodox Easter celebration on May 2 as "an opportunity for inner renewal and a source of spiritual consolation."

Although Russia's defense minister, Sergei Shoigu, promised a week later that some forces would be pulled back, sources on the ground told NCR this has made little difference.

"People still fear, and even expect, a direct Russian intervention at some stage," said Archpriest Oleg Panchynyak, information director for Ukraine's Greek Catholic Church, an Eastern rite tradition in communion with Rome that was savagely persecuted under Soviet rule.

"Although our army is slowly and gradually restoring control where it can, instability and unease have been constant themes across our eastern regions for the last 30 years," said Panchynyak. "Those with power on the ground seem determined not to allow us any grounds for hope."

Visiting the Ukrainian capital, Kyiv, on May 6, U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken assured President Volodymyr Zelensky that the American government was giving "very active consideration" to boosting military and security aid.

Members of Ukraine's Roman and Greek Catholic churches fear cities such as Kharkiv and Odessa would lie in the immediate path of a Russian invasion.

The situation of those churches has also worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has harmed economic conditions and made the once rapidly expanding denominations again heavily dependent on help from Western church aid groups.

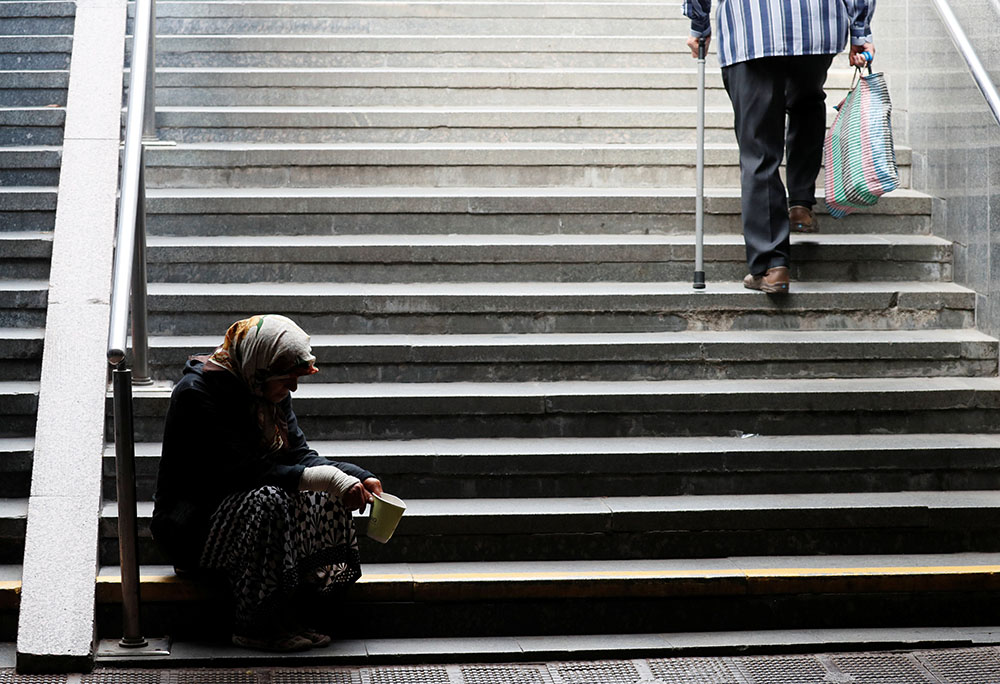

An elderly woman in Kyiv, Ukraine, begs for money in an underpass Sept. 11, 2020, amid the coronavirus pandemic. (CNS/Reuters/Gleb Garanich)

In separatist-occupied Luhansk and Donetsk, meanwhile, church practices have all but ceased, other than for followers of Ukraine's Moscow-linked Orthodox Church.

"The situation is especially complicated for Greek Catholics, since our very existence as a lively church ... has always posed a problem for those loyal to Moscow," said Panchynyak.

"Those wishing to use religion for their own purposes, as a fifth column and route to power, will never accept us," he said. "So Greek Catholics have been warned not to raise voices or seek any kind of help. Those still in these areas are simply praying quietly in hopes of avoiding worse trouble."

With Catholic Masses allowed only sporadically, and even online services blocked by internet disruptions, Sobilo fears the whole Catholic church could begin to die out in eastern Ukraine as more and more young families flee.

"We've urged parishioners to stay, since this is their country and they're needed here — and we're praying for an end to the conflict, so people could still build a future here and save the church," said 58-year-old bishop.

"But it's hard to see them doing so, when Ukraine seems to have so little to offer them," he said.

Ukraine has faced severe problems since its parliament, the Verkhovna Rada, declared independence from the Soviet Union in August 1991.

In February 2014, its pro-Russian president, Viktor Yanukovych, was ousted by mass protests that called for the country to be brought closer to NATO and the European Union under the pro-Western Petro Poroshenko. The protests left more than 100 dead.

Russia responded by annexing Crimea and stoking separatist violence, while Ukraine's capacity to resist was reduced by internal problems, including rampant corruption.

Deep religious tensions are also at work in Ukraine.

Orthodox Christians traditionally make up 70% of the population, currently 43.46 million, and are divided between a Ukrainian church under the jurisdiction of Russia's Moscow Patriarchate, and a new independent Orthodox Church of Ukraine, which broke away two years ago.

Advertisement

Russia's Orthodox Church angrily severed relations with Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I, the Orthodox world's honorary primate, for decreeing an end to its 332-year ecclesiastical jurisdiction over Ukraine and granting the new church self-governing status in January 2019.

The Russian Orthodox Church has since also cut ties with the churches of Greece, Cyprus and Alexandria for recognizing the new Ukrainian denomination.

Meanwhile, lawsuits have multiplied in Ukraine as parishes once loyal to the Moscow Patriarchate have opted to join the new church, which expects to host a visit by Bartholomew later this year for Ukraine's 30th anniversary of independence.

The new church's 42-year-old leader, Metropolitan Epiphanius, has been bullish about the Russian threat, blaming Patriarch Kirill of Russia for fueling President Vladimir Putin's territorial ambitions, and accusing Ukraine's Moscow-linked church of acting as a fifth column.

"Do not participate in the crimes of your superiors, but pay attention to the words of Scripture — this also applies to those in Ukraine who await the arrival of Putin on a path of betrayal and servitude," the church's governing Holy Synod told Russian service personnel in April.

The Moscow Patriarchate has accused Ukraine of persecuting the Russian Orthodox Church, seizing its places of worship and pressuring its communities to desert to the new church.

The acerbic inter-Orthodox dispute has posed problems for Ukraine's Catholics.

"If we have contact with one, the other takes offense — if we pray with a bishop from the new Kyiv church, this angers bishops from the Moscow church," explained Sobilo.

"Meanwhile, if we show any sympathy for the new church in separatist areas, where it's seen as illegal, this can turn out badly for us, when they've already delegalized our parishes and expelled our clergy," said the prelate.

Auxiliary Bishop Jan Sobilo of Ukraine's Kharkiv-Zaporizhia Diocese (Courtesy of Jan Sobilo)

This has not prevented the Ukrainian government from seeking Catholic help.

On April 28, the Religious Information Service reported that Ukraine's deputy foreign minister, Vasyl Bodnar, had discussed the humanitarian situation with Msgr. Miroslav Wachowski, the Vatican's deputy foreign minister.

In an interview the same day with Italy's La Repubblica daily, Zelensky said he believed the Vatican might even be "an ideal place" for peace talks with Putin.

At present, a Vatican summit seems improbable.

Putin has previously told Zelensky he must come to Moscow, and that peace can only be discussed if the Ukrainian president first initiates talks with separatist leaders. For all the pope's moral authority, the Russian president and his Orthodox allies are unlikely to agree to papal involvement.

"The emergence of a new Orthodox Church has completely changed the situation, giving Orthodox Ukrainians a real choice over where to place their loyalties — so any engagement by the Vatican in this tense situation is certain to encounter resistance," said Panchynyak.

"As Ukraine looks for friends, it also has many painful problems to resolve, particularly when people have gained power here with no proper upbringing or regard for the common good," he said. "We need a wider cultural change, and this is something the Catholic church of both rites is best positioned to promote and argue for."

For now, at least, the dangerous "frozen conflict" in eastern Ukraine looks set to drag on, impeding the country's hopes of drawing closer to NATO, the European Union and the United States as a secure and stable country.

While Russia's intimidatory tactics continue to fuel fears of a mass civilian exodus, the death toll of Ukrainian soldiers for 2021 currently stands at 36.

Cease-fire appeals for the Orthodox Easter celebrations passed unheeded, with drone movements and machine-gun fire reported at several points on the 270-mile "line of control."

Meanwhile, on May 9, Russia's Victory Day was marked with a massive military display in Moscow's Red Square, and stern pledges by Putin to defend his country's interests.

Sobilo thinks Ukraine's best hopes lie in eventual accession to NATO and a close alliance with the U.S., which has promised a $125 million military aid package, as well as help in building up Ukraine's democratic institutions.

"Ukraine needs to be certain it can be defended, in the fullness of time, with help from key Western friends and advocates," the Kharkiv-Zaporizhia auxiliary told NCR.

"This is vital for those who wish Ukraine to be independent and free forever," he said. "If the U.S. doesn't help, and if NATO doesn't accept us, we'll be condemned to live in fear under constant threat from the east."