New York Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Massachusetts Sen. Ed Markey lead a press conference to unveil the Green New Deal in Washington, D.C., Feb. 7. (Flickr/Senate Democrats)

"Everything is connected."

With those words, Pope Francis began Paragraph 91 of his landmark encyclical "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home." He continued:

"Concern for the environment thus needs to be joined to a sincere love for our fellow human beings and an unwavering commitment to resolving the problems of society."

If you didn't know better, you would think the pope was referring to the much-dissected and intensely debated Green New Deal.

The Green New Deal is a 14-page nonbinding congressional resolution that outlines an ambitious, major mobilization to transition the United States away from fossil fuels in an effort to curb climate change below dangerous warming levels, and with it address inequality and "systemic injustices" in labor, race, gender, housing and health.

Sponsored in the House by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-New York, and in the Senate by Sen. Ed Markey, D-Massachusetts, it sets a goal for the country to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 by generating 100% of electricity from clean, renewable, zero-emission energy sources and investing in infrastructure, smart grids and high-speed rail.

In addition, the Green New Deal promises to create millions of high-wage jobs and ensure for everyone both economic security, including a family-sustaining wage, and access to clean air, clean water and a sustainable environment. It pledges to "work collaboratively" with farmers and prioritize investment, training and job creation in marginalized communities and those transitioning away from fossil fuel industries. The resolution adds it would "promote justice and equity by stopping current, preventing future, and repairing historic oppression of ... frontline and vulnerable communities."

On March 26, the Senate voted down advancing the Green New Deal resolution, though many Democrats, the majority of whom voted present, viewed it as a "political ploy" by Majority Leader Sen. Mitch McConnell. That has not stopped the great debate on the Green New Deal.

Republicans have levied their share of criticisms, but they have not been alone. Some Democrats, including one presidential hopeful, have declined to endorse the Green New Deal, as have labor unions. Ernest Moniz, former energy secretary under President Barack Obama, said it was "impractical" to achieve zero-carbon in a decade, and has joined others in issuing their own proposal.

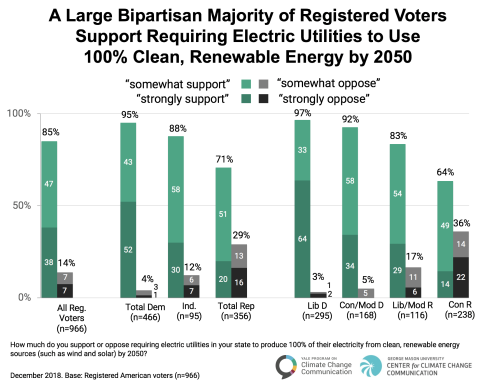

Polling conducted late last year by Yale University and George Mason University shows wide support across political lines for rapidly shifting the U.S. energy grid to clean renewable energy.

But the broad scope of at-first-glance unrelated issues all wrapped into one proposal quickly turned the Green New Deal into a target for attacks as socialist, radical, unrealistic, "a Trojan Horse of liberal goodies," and (inaccurately) spelling the end of planes, the military, hamburgers and milkshakes.

In a way, just like Laudato Si'.

When Francis' encyclical on the environment and human ecology was released publicly in June 2015 — and in some cases, even before — the document was cast by some as "anti-modern," "Marxist," "socialist" and "communism," and Francis labeled a "Red Pope." And then there was the whole blowback to the pope's views on air conditioning.

That the Green New Deal is championed by Ocasio-Cortez, the freshman congresswoman and self-described democratic socialist, has only ramped up the criticism. When confronted with descriptions of the plan, or herself, as "radical," she has embraced the label, telling "60 Minutes" in January, "I think that it only has ever been radicals that have changed this country," before pointing to presidents Abraham Lincoln and Franklin Roosevelt.

Nor has Francis or the Vatican shied away from the "radical" word when it comes to addressing climate change, or as the pope put it at one point in his encyclical "the radical change which present circumstances require."

"The same mindset which stands in the way of making radical decisions to reverse the trend of global warming also stands in the way of achieving the goal of eliminating poverty. A more responsible overall approach is needed to deal with both problems: the reduction of pollution and the development of poorer countries and regions," Francis wrote in Paragraph 175.

'It reflects what Francis is up to'

Similarities between the two documents go beyond reception.

A starting point is Francis' reflections on integral ecology, the idea that humanity is not separate from but a part of nature, and that solutions to environmental and social issues require consideration of all factors and perspectives. In Laudato Si', Francis devotes all of Chapter 4 to the topic.

"I say, 'No, it is not a green encyclical, it is a social encyclical,' because we cannot separate care for the environment from the social context."

—Pope Francis

"The cry of the poor and the cry of the earth are inextricably linked," Creighton University theologian Richard Miller said, referencing a much-cited line in Laudato Si'.

Miller, author of God, Creation, and Climate Change: A Catholic Response to the Environmental Crisis, pointed to the Green New Deal's treatment of not just climate change but issues of wages, labor and power as consonant with Francis' understanding of integral ecology. Add to that its consideration for the common good and inclusion of all parties — particularly frontline and vulnerable communities, which often experience the impacts of climate change most acutely — and the Green New Deal, he said, sets up principles that are in line with what Francis says are necessary to address both environmental and social problems.

"It reflects what Francis is up to," Miller said.

At various points in Laudato Si', Francis discusses environmental degradation in terms of water and land use, urban development and housing, abortion and family, technology and transportation. All that in addition to the overarching religious dimension.

Just a month after the encyclical's release, Francis was quick to dispel descriptions of Laudato Si' as solely an environmental document: "I say, 'No, it is not a green encyclical, it is a social encyclical,' because we cannot separate care for the environment from the social context, the social life of mankind. Furthermore, care for the environment is a social attitude."

Pope Francis addresses mayors from around the world at a workshop on climate change and human trafficking in the synod hall at the Vatican July 21, 2015. Local government leaders were invited by the pontifical academies of sciences and social sciences to sign a declaration recognizing that climate change and extreme poverty are influenced by human activity. (CNS/Paul Haring)

That sentiment is reflected in one of its most-quoted sections, where Francis stressed, "We are faced not with two separate crises, one environmental and the other social, but rather with one complex crisis which is both social and environmental. Strategies for a solution demand an integrated approach to combating poverty, restoring dignity to the excluded, and at the same time protecting nature."

"In some senses, I think the [Green New Deal] resolution tries to address that," Dan Misleh, executive director of Catholic Climate Covenant, told NCR. "You know, we have enormous poverty in this country and enormous wealth and there's a huge gap. So can we find ways to use the new green economy to help close that gap, so we're taking care of the planet, we're taking care of people?"

Everything is connected

The interconnected theme runs throughout Laudato Si', with Francis repeating a version of the phrase "everything is connected" a half dozen times. "It cannot be emphasized enough how everything is interconnected," he concluded Paragraph 138, as if to fully drive the point home.

Earlier in that same graph, Francis explained ecology as the study of "the relationship between living organisms and the environment in which they develop. This necessarily entails reflection and debate about the conditions required for the life and survival of society, and the honesty needed to question certain models of development, production and consumption."

A man walks through a flooded street Oct. 10, 2018, after Hurricane Michael swept through Panama City Beach, Florida. (CNS/EPA/Michael Anderson)

In Paragraph 92, he quoted a 1987 pastoral letter from bishops of the Dominican Republic: "Peace, justice and the preservation of creation are three absolutely interconnected themes, which cannot be separated and treated individually without once again falling into reductionism."

In Paragraph 93, Francis wrote: "Whether believers or not, we are agreed today that the earth is essentially a shared inheritance, whose fruits are meant to benefit everyone. ... Hence every ecological approach needs to incorporate a social perspective which takes into account the fundamental rights of the poor and the underprivileged."

And in Paragraph 111, he stated: "Ecological culture cannot be reduced to a series of urgent and partial responses to the immediate problems of pollution, environmental decay and the depletion of natural resources. ... To seek only a technical remedy to each environmental problem which comes up is to separate what is in reality interconnected and to mask the true and deepest problems of the global system."

Such passages reflect the connectedness of all things that has been a constant in Catholic teaching since the church's beginning, said Jame Schaefer, an associate theology professor at Marquette University who specializes in ecological ethics.

From St. Paul's letter to the Corinthians about the body of Christ, to the writing of St. Thomas Aquinas, to present-day papacies, she said the church has long invited reflection on how the parts relate to the whole, that they are "all part of the whole scene, and one cannot be denigrated or avoided."

Pope Francis meets March 8 at the Vatican with representatives of the world's religious traditions and experts in the fields of development, the environment and health care. The group was meeting at the Vatican March 7-9 to discuss the contributions religions can make to achieving the U.N. sustainable development goals in a way that responds to the needs of the poor and respects the environment. (CNS/Vatican Media)

She likened the Green New Deal's aspirations to the United Nations' sustainable development goals, themselves the focus of a Vatican conference in March that Schaefer attended.

"In the Green New Deal, we have to see connectedness, all of these components that are being proposed. And all need to be dialogued about," Schaefer said.

Indeed, Francis began Laudato Si' with an appeal "for a new dialogue about how we are shaping the future of our planet. We need a conversation which includes everyone."

The attention to the Green New Deal has elevated discussion on climate change to a degree not seen in Congress in nearly a decade with the failed 2010 cap-and-trade bill. All at a time when scientific reports indicate as few as 12 years to take action to avoid the most dangerous consequences of climate change.

As for inclusivity, the Green New Deal resolutions state it would invite all into the conversation: Dialogue with poor and marginalized communities. Dialogue with farmers. Dialogue with deindustrialized communities to ensure a just transition as coal mines close and power plants shutter.

"In the Green New Deal, we have to see connectedness, all of these components that are being proposed. And all need to be dialogued about."

—Jame Schaefer

That type of engagement with different levels of society, and not necessarily from the top down, reflects the Catholic principle of subsidiarity, Miller said.

He noted the resolution mentions several times the "duty" of the government to address climate change, consistent with what scientific reports have indicated. In October, the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issued a report stating global carbon emissions would need to drop 45 percent from 2010 levels by 2030 and reach net-zero by 2050 to hold temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

"This would require massive government engagement to shift society. There's no way out of that," he said.

Ambitious goals for the common good

So far, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has not staked out a position on the Green New Deal, instead focusing attention on a House bill that would place a fee on carbon emissions. At least two faith groups, Franciscan Action Network and the interreligious GreenFaith, have lent support to the resolution.

Misleh of Catholic Climate Covenant called the Green New Deal "totally politically untenable." Still, he was happy that the resolution raises "this notion of the common good," something he said rarely penetrates policy discussions.

"Embodying those [principles of the common good] into public policy solutions is always tricky, but there has to be some attempt to do that," he said.

Advertisement

Despite any parallels, there's no indication that the Green New Deal resolution drafters drew from Laudato Si' in the process. The offices for Markey and Ocasio-Cortez did not respond to requests for comment.

Still, the Massachusetts senator has been a vocal supporter in the past of the pope's messages on climate change and the environment.

"Pope Francis and the encyclical give us the opportunity to examine our own policies, the impact they have on our country and our planet," Markey said at a September 2015 conference at Boston College on climate change. Cardinal Peter Turkson, one of the primary drafters of the encyclical, also attended the event.

On the Senate floor Feb. 27, Markey said, "The Green New Deal resolution is bold, it's aspirational in its principles, but it's not prescriptive in its policies."

Schaefer, the Marquette theologian, told NCR that it is good that both the Green New Deal and sustainable development goals have set ambitious targets. "We need lofty goals," both nationally and internationally.

She added they provide "a vision for the future, and some direction of how to get there."

An electrician takes a lift up to 30 feet before sunrise to start string-wiring 2,700 panels on a new solar energy grid in Phoenix in November 2016. (Flickr/U.S. Department of Energy/Michael Nothum)

In that way, the Green New Deal and sustainable development goals help instigate dialogue, Schaefer said, and hopefully, "some serious discussion" that prompt ideas for action at all levels of governance.

That said, she still held reservations about the resolution in terms of subsidiarity, that it may place too much focus on solutions from the federal level.

"We can't always push this off to a higher level without doing something ourselves to the utmost of what we're able to do," she said, pointing to steps taken on climate change in Milwaukee where she lives.

Misleh said that the Green New Deal may provide a starting point for discussion, but that ultimately technical solutions alone won't work.

"There has to be a change in the heart and in the spirit," he said, "and again, that's really the role of religion. And it's a vital role."

[Brian Roewe is an NCR staff writer. His email address is broewe@ncronline.org. Follow him on Twitter: @BrianRoewe.]

Editor's note: To keep up with Catholic environmental news, sign up here for the weekly Eco Catholic email newsletter.