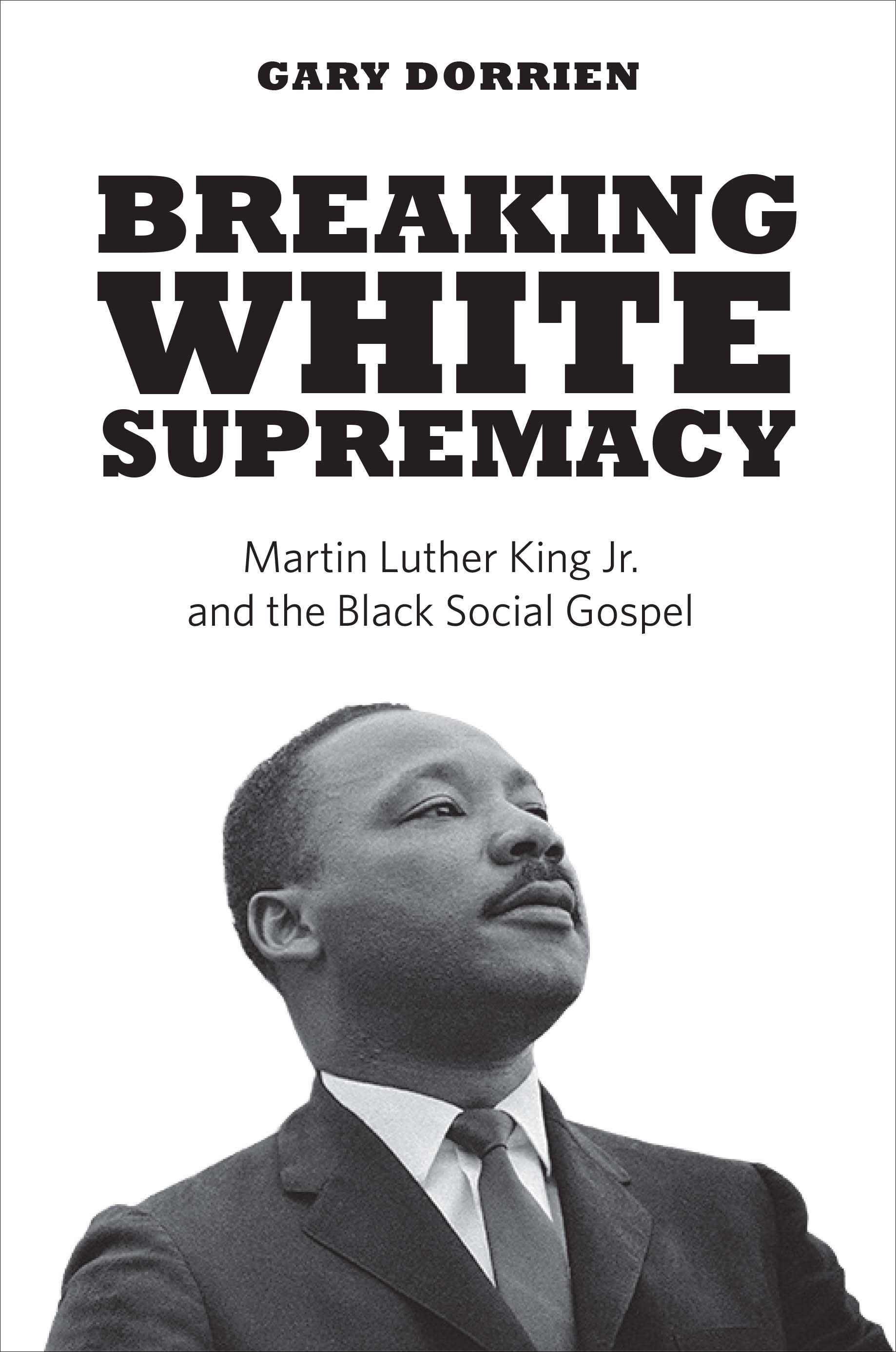

A woman holds a portrait of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. during the 2011 dedication of the King memorial at the National Mall in Washington. (CNS/Reuters/Yuri Gripas)

In 2018, we marked the 50th anniversary of the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. It is a fitting time to relook at the life and witness of this young black Baptist minister and the historic impact his life, brief as it was, had on the history of the United States and the world.

Gary Dorrien, in this massive, thoroughly researched work, expands on an assertion first made in an earlier work, The New Abolition: W.E.B. Du Bois and the Black Social Gospel. In that work, he looked the founders of the black social gospel movement, ministers like Reverdy C. Ransom, Henry McNeal Turner and Richard Wright (all three of the African Methodist Episcopal Church) and Alexander Crummell (Episcopal), as well as activist women such as Nannie Helen Burroughs and Ida B. Wells-Barnett.

As the author notes, and gives evidence for, the white social gospel movement, although it paved the way for the ecumenical church movement as well as the move by ecumenical churches to address issues of social justice in the society around them, it failed massively in addressing the needs and concerns of persons of African descent in the U.S. The original social gospel movement saw no need for and had no interest in racial justice issues.

Others in the black community did, however. In the aftermath of the failure of Reconstruction, they began to assess how the black church might address not just the religious needs of their black congregants but also their political, social and economic needs.

As Dorrien notes in his earlier work, they were not well-received, but rather were castigated by other black ministers for bringing the world into the church. Despite the black church's historically holistic perspective that did not separate the sacred and the secular, increasingly in the aftermath of the Civil War the black church seemed to be turning away from its roots in racial and social uplift and moving into a sacred space that pursued heaven rather than the improvement of black lives on Earth.

Dorrien writes, "Black social gospel leaders worked hard at building communities of resistance; they operated in the intertwined spheres of religious communities and movement politics, and they focused on racial justice." This work reveals how the black social gospel movement was kept alive and passed on, serving as a creative source and foundation for the ministry of King. As Dorrien further notes, "By 1995 I had a strong conviction that scholarship on the black freedom movements, progressive Christianity, and U.S. American history wrongly overlooked the very existence of the black social gospel tradition, let alone its immense importance."

Advertisement

In Breaking White Supremacy, Dorrien lays out this critically important history and tradition by delving into the lives and ministries of 20th-century men and women who followed in the footsteps of founders like Booker T. Washington and Du Bois. In seven detailed and insightful chapters, he explores the lives and careers of King's mentors, teachers and friends.

Mordecai Johnson, the first black president of Howard University, lectured on the black social gospel for decades but was never able to engage in civil rights activism because of the demands of his presidency. His speeches compelled King to rethink his own perspectives while a student and fledgling minister.

Benjamin Mays, a man of great intellect, became president of Morehouse College, where he took King, still in his teens, under his wing. Next is Howard Thurman, whom some see as the first black liberation theologian, but whose emphasis was on spirituality and ecumenism.

Each of these men was seen as a possible American Gandhi who would lead black Americans into freedom from the racism and prejudice that entrapped them. All of them espoused the end of Jim Crow through their lectures and writings, but none could take the next step of leading a civil rights movement that would impact the U.S.

An important perspective this book raises is the presence, or absence, of black women in this movement. Women were present and active, the author writes, but their actions and achievements went unnoticed, unacclaimed and unrewarded. This was due, sadly, to the predominance of patriarchal men, mostly Baptist ministers, who were not open to the ordination or even participation of women.

From left: Mordecai Johnson (Library of Congress/Harris & Ewing); Fannie Lou Hamer (Library of Congress); Rosa Parks (Library of Congress/P&P); Pauli Murray (AP photo)

Ella Baker, who helped found both the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, was "let go" from the conference when she sought a leadership position in the institution. Dorrien carefully weaves in her story as well as those of Burroughs and Wells-Barnett, Fannie Lou Hamer, Rosa Parks and others whose roles were, in actuality, critical to the tradition's development.

The concluding chapter on Pauli Murray, a lawyer and the first black female to be ordained an Episcopal priest, reveals how her story overlaps with the entire story of the black social gospel tradition and the civil rights movement; yet, because of a tradition that silenced women, she never gained entry.

King was raised in the black social gospel tradition of the black Baptist church community that maintained and sustained his life. Although he spoke more of his seminary and graduate training in personalist theology and democratic socialism, he was still a black Baptist minister who stepped into a role that had been waiting for him since slavery's end.

The perennial question of those who had been influenced by Mahatma Gandhi's actions in India as well as the situation of blacks in the U.S. was: "Where is the American Gandhi?" They found him in a little church in Montgomery, Alabama: Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. On the night of the first mass meeting, King rose to speak to the question of continuing the bus boycott in that city, and by the end of his galvanizing, inspirational sermon, America's Gandhi had entered history.

This book is a compelling work that provides insight into the radical King, rather than the domesticated version that most of the world became familiar with after his death. It is a King who stood against not just racism, but poverty and militarism. Dorrien peels back the layers of a complex, radical preacher who sought to change the world as Jesus did for all.

[Diana L. Hayes is professor emerita of systematic theology at Georgetown University.]