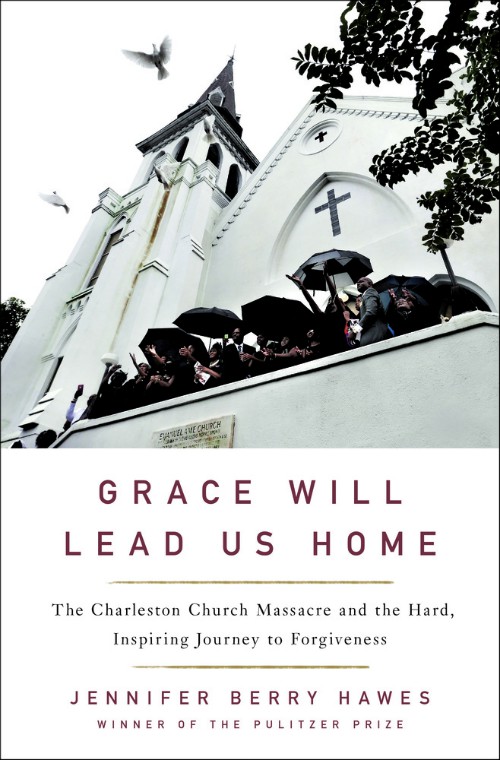

A man pays his respects outside Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, June 21, 2015. Nine African-Americans were shot to death by Dylann Roof at an evening Bible study inside the church June 17, 2015. (CNS/Brian Snyder)

Jennifer Berry Hawes' Grace Will Lead Us Home is both beautiful and horrific, somehow at the same time. In crisp, evolving sentences, it opens up the horror of the massacre that took place at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church on the evening of June 17, 2015. But more importantly, the author goes beyond it so that, despite the horrific act that took place there that night, we are shown, through Hawes' balanced and in-depth writing, a different or, perhaps better said, a larger story than we had known.

Hawes is an investigative journalist who, in the process of getting back behind the story of the massacre itself reveals a bitter yet at the same time encouraging truth. She has carefully unpeeled the layers of pain and anger, sorrow and forgiveness, hatred and love to show us what lies beneath. What sustains ordinary people in a time like this? What helps them to continue with their lives?

As we see in this elegant book, it is not easy. Life must go on, but how and why is not easy to get to.

Hawes begins with the day itself, an ordinary summer evening. Emanuel AME had a busy schedule of meetings that evening, including a Bible study class, which was delayed for some time. There were thoughts of canceling but the faithful had gathered and were waiting patiently for it to start whenever it started.

It has to be asked: What if it had been canceled? What if when Dylann Roof, the killer, had arrived, there was no meeting taking place? Would he have gone home? Would he have shot whomever he saw there? Would he have wandered off and shot people in the streets or elsewhere?

The answer to these questions will never be known because, of course, the meeting was held and Roof, armed with 88 rounds of ammunition, appeared and shot nine people. Why? Because he had to do it. Why? Because blacks were taking over and raping their (white) women. Why? Why? Why? Truly there is no real answer.

Roof was a loner, alienated, confused, desperately seeking something to make sense of his life. And he does. Hawes shows how, over time, he discovered online the voices of others who saw themselves as alienated. He found comfort and a home of sorts in white supremacy and the Aryan Nations, reading the online newspaper the Daily Stormer and other resources. And so, he planned a massacre.

But why? Why the Bible study group at Emanuel? Why Pastor Clementa Pinckney? Why the old and the young, the infirm and the healthy?

These are questions we ask ourselves as we continue to read. Hawes details the lives and stories of each victim and the survivors, the husbands and wives who sought understanding and guidance from their church but strangely were ignored. She looks at those brought in to lead them in Pinckney's place and how they became caught up in a battle over money and prestige.

Why were those who suffered ignored? Why did no one reach out to them? They were left to find their own way as a result, and several, like Felicia Sanders, left and joined, ironically, a white church.

Others, like Ethel Lance, saw divisions that had already begun in their families grow even larger, leaving them unsure of who they were and what they were doing. The fissure in the family resulted in their mother's grave having two headstones rather than one.

Advertisement

Steve Hurd, a merchant marine, became a recluse, condemning himself for not being there when his wife so badly needed him. Pinckney's wife, Jennifer, found herself pulled out of anonymity into the blinding light of press conferences, interviews and other assaults on the tenacious hold she had on herself, her sanity and her daughters.

Yet somehow, in the midst of the grief and the pain and the horror, some found it within themselves to forgive Roof. They forgave him despite his stoic demeanor and impassivity. They forgave him because they wanted to see God in heaven, to see their loved ones in heaven, because it was the right thing to do. They forgave while others raged, screamed and called Roof evil.

How is that possible? The author does an admirable job of bringing out all of the "mess" thrown up by this horrific act of hatred. She shows the South Carolina legislature caught up in its own battles over the Confederate flag, over forgiveness, over what to do next.

She ably shows the pain and anguish of the victims and survivors and those around them. She provides the reader with so many details that it is at times necessary to simply put the book down and walk away because you can't read yet another page; it gets under your skin and in your mind and burrows deep.

Roof had wanted to plead guilty and have no trial, but the prosecutors and many family members of victims wanted the death penalty, so they had a trial. Roof served as his own lawyer and did little to help himself. He did so because he didn't want his attorneys to try to present him as unable to stand trial or serve a sentence because of his mental state and the possibility that he was autistic.

His parents came the first day but never again. His grandparents came several days. He paid no attention to them or anyone else. He was found guilty of all charges.

After the sentencing, it was pretty much all over. What to do now?

Where to go, how to live, with a hole torn in your life? Somehow life goes on. Funerals take place. People begin to forget.

But as the author clearly shows, a hole was torn in the lives of countless blacks still seeking to understand why, why, why. The lives of others were affected as well, as some fought alongside the survivors for stronger gun laws and others sought to help those who, for whatever reason, could not seem to help themselves. Life goes on but it will never be the same.

[Diana L. Hayes is professor emerita of systematic theology at Georgetown University.]