(Unsplash/Guilherme Stencnella)

In the name of the Bee-

And the Butterfly-

And the Breeze-Amen!

Is this riff on the "sign of the cross" by Emily Dickinson blasphemy or does it lead the reader to some fresh understanding of nature as the source of mystical inspiration? It was Augustine who first claimed that God wrote two books — the book of creation and the book of Scripture — both of which revealed God. Using this as his premise, Msgr. Charles M. Murphy calls his little book a poetic "example" of Dickinson's poetry as mystical prayer borne from her acute awareness of the natural world.

Do not expect to find here a thorough or critical treatment of Dickinson's life or work. That literature is extensive. Neither is the topic of mystical prayer explored in any depth. Rather the charm of this long essay is as a personal reflection on Dickinson's poetry. Murphy is author of multiple volumes, one of which is an exploration of Wallace Stevens, whom he defined as a spiritual poet in a secular age. In Dickinson, who lived in a more religious time, Murphy faces other challenges.

Murphy sets the "recluse" of Amherst within her prominent family, her historical time — the mid-19th century — and her cultural/religious context of a sin-haunted Calvinism, a tradition against which she rebelled. Although her exterior life was quotidian, her inner life was rich, and it was there that she "wrestled with God" and contested the constraints of her too-small world. Murphy calls her a "believing unbeliever." It was from her conflicted and imaginatively vivid inner life that she produced her poems.

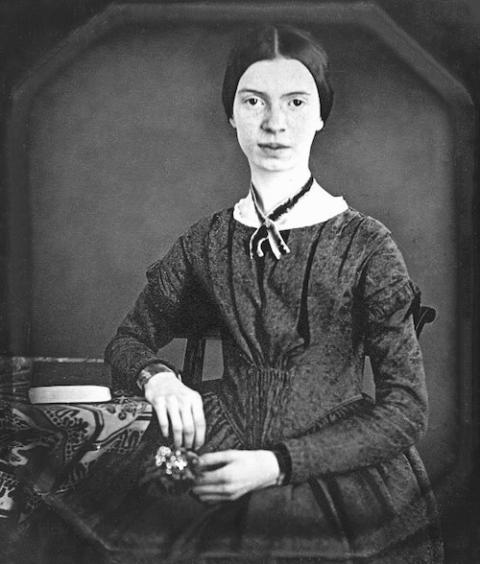

Dickinson's life was relatively short — she died at 56 — and uneventful as she passed her days self-restricted in her movements and contacts. Like the verses of Gerard Manley Hopkins and Thomas Traherne, her poetry was largely unknown to her contemporaries. It was only after her death that her 1,800 poems became available and only later that voluminous scholarship on her life and work began.

Finding in Dickinson's poetry an awareness of "God's presence everywhere and always," a characteristic of mystical writing, Murphy in this accessible essay puts her in conversation with the Christian mystical tradition. His principal interlocutor is Teresa of Avila. He defines three aspects of the mystical tradition — solitude, asceticism and place — and considers parallels in Dickinson's life. Her cloister was her room, and it was there she lived the silent, creative life which liberated her and allowed her to reject the false identities given her by family, culture and religion. Dickinson's tenacious attachment to this place brought her to focus attentively and relentlessly on the natural world around her. As a gardener she was entranced with trees and flowers. In nature she found God, and it was from that experience she could proclaim with the psalmist that: "The heavens declare the glory of God, and the firmament proclaims his handiwork."

Advertisement

Daguerreotype of Emily Dickinson, taken circa 1848 (Wikimedia Commons/Todd-Bingham Picture Collection and Family Papers, Yale University Manuscripts and Archives)

Murphy sees Dickinson's rejection of her Puritan heritage and her unwillingness to darken the door of a church as defying her inherited notion of God. This brought her to turn to nature as both a revelation of God and the place of encounter with God's real and true presence. As such nature took on a "sacramental" aspect, opening her to ultimate reality. In her wrestling she claims to discover that "the supernatural is only the natural disclosed." In so doing she discards the usual separation between the natural and the supernatural is discarded. Her "sign of the cross" is no blasphemy; the "bee," the creator, the "butterfly," the liberator, the "breeze," the sustainer, are primary metaphors for God found in nature.

If Murphy prompts the reader to consider nature as Dickinson's source of inspiration, he does less well confirming that in finding God she found herself. While this insight from the Christian mystical tradition may be true, more serious consideration is needed to show how that is true for her. Nonetheless, readers will be stimulated by Murphy's exploration of Dickinson's poetry as a small but provocative contribution to the understanding of one of America's most important and well-loved poets.

[Dana Greene is author of biographies on Evelyn Underhill, Maisie Ward, Denise Levertov and Elizabeth Jennings.]

Editor's note: Love books? Sign up for NCR's Book Club list and we'll email you new book reviews every week.