Mosaic portrait of St. Thomas More (Wikimedia Commons/Pablo Sanchez)

In a time when the Catholic Church in the United States is flirting with Communion bans and populist nationalism, it's good to consider anew why Thomas More, the patron saint of politicians, is not a culture war hero.

More's feast day on the calendar of saints is June 22 (accordingly, the day when the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops launches its annual Religious Freedom Week). He was martyred in 1535 after he refused to accept the Act of Supremacy by which Parliament made King Henry VIII the head of the Church of England.

Beneath that great political battle lay a more personal one: Henry wanted Pope Clement VII to grant him an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon so that he could marry Anne Boleyn. And the king wanted More's approval of the annulment. More refused that as well. He was made a saint in 1935 and named the patron of politicians by John Paul II in 2000.

More was indeed a remarkable man and a great saint. A brilliant humanist and lawyer, he wrote the classic Utopia at the height of the Renaissance; played a major role in the development of English common law; and served as lord chancellor of England under Henry VIII until his resignation in 1532.

In the last decades, More was made famous anew by the power and popularity of Robert Bolt's play "A Man for All Seasons" (which became a movie as well). For a vivid sense of the courage, humanity and holiness of the man, I suggest Peter Ackroyd's magnificent biography, The Life of Thomas More.

Advertisement

Here are four principles by which to interpret this luminous figure who hovers over our times as inspiration and challenge.

It wasn't only about the marriage

At first glance, More is the perfect saint for the conservative Catholic inclined to think that the great political issues of our time have to do with the intersection of law and church teaching on sex and marriage. Indeed, after he was convicted at his trial, More told the court: "It is not for this Supremacy so much that you seek my blood, as for that I would not condescend to the marriage."

But it is important to consider More's final struggle in light of the longer arc of his opposition to tyranny. Decades before his own death at the hands of Henry, More lamented the tyrannical actions of the Tudor king manifest in the execution of political opponents, the instigation of foreign wars and the encroachment on the liberties of the church. Moreover, he dissected the vices of tyranny in Utopia and in his work called History of Richard III.

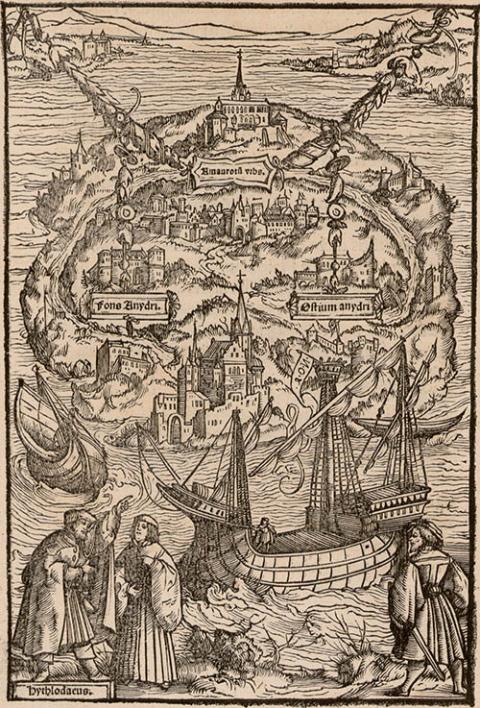

An illustration from the March 1518 edition of St. Thomas More's book "Utopia" (Wikimedia Commons/Universitätsbibliothek Basel)

We reduce More to a culture war figure if we link him only to disputes over law and sexual ethics. We see him in his proper light when we consider the breadth and depth of his opposition to the tyrannical impulses of a leader whose appetite for power became the measure of right and truth (a phenomenon belonging to kings and presidents).

Freedom of the church: yes and no

More was not a type of the lonely modern hero. Rather, he was a man of the church. He understood his conscience to be in communion with the mystical body of Christ. He saw in the primacy of the pope a guarantor of the freedom of the Catholic Church in England and thus a guarantor of the protection of conscience from the aggressive encroachment of the king.

As the Vatican Proclamation of More as Patron of Statesmen put it: "St. Thomas More gave his life to defend the Church's freedom from the State. But in this way, he also defended the freedom and the primacy of the citizen's conscience before the power of the state."

To be sure, the freedom of the church is an inalienable Catholic theological claim before the power of the state. Dignitatis Humanae, the 1965 Declaration on Religious Freedom from the Second Vatican Council, explained: "This is a sacred freedom, because the only-begotten Son endowed with it the Church which he purchased with His blood."

But it is important to note the problematic ways the concept can be deployed in the struggles over religious freedom in the present day.

First, the notion of the freedom of the church can become the de facto justification for religious freedom at all. That way of putting things not only diminishes the significance of the argument from the Declaration on Religious Freedom that the right to religious freedom is based on the dignity of the human person, but it also tends to make religious freedom the right of a collective more than the right of the individuals who constitute the collective.

Furthermore, an emphasis on the freedom of the church can also signal the view that the freedom of conscience in civil society depends on the freedom of the church from the encroachment of the government. But this is too one-sided a way of putting the relationship between the freedom of the church and the freedom of conscience (as the next interpretive principle makes clear).

More was a hero of conscience who persecuted heretics

As Lord Chancellor, More presided over the execution of heretics. Of Richard Bayfield, a former Benedictine monk who was found with banned books, More said: "The monk and apostate [was] well and worthily burned at Smithfield."

Biographer Ackroyd notes: "His opponents were genuinely following their consciences, while More considered them the harbinger of the devil's reign on earth."

The tomb of St. Thomas More is seen in the crypt of the St. Peter ad Vincula chapel in the Tower of London. (CNS/Marcin Mazur)

More's involvement in such practices is inhumane to us. And while we can't simply judge him by our standards, we also can't forget that for him the freedom of the church may have been a guarantor of the freedom of conscience of Catholics, but it wasn't a guarantor of the freedom of conscience of others, like the alleged apostate monk burned at Smithfield.

Indeed, it took centuries after More for the church to affirm a right to religious freedom based on human dignity that applied to everyone, Catholic and heretic alike. To remember More's persecutorial faith is to recall the intolerance lurking at the door of the freedom of the church.

For the sake of religious freedom, it's time to pair Thomas More with Bartolomé de las Casas

More represents the high-water mark of the medieval Catholic Church in England. But it's illuminating to pair him with a 16th-century contemporary who risked life and limb on the other side of the world to stem the rapacious tide unleashed on Indigenous peoples in the lands known as the Americas.

The Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas for decades called out the genocide of native persons driven by the mix of cross and sword, church and crown in Spain. Indeed, we forget that at the heart of the entire colonial effort were assumptions about the diminished religious freedom of Indigenous persons that made them fit objects of violence.

We need to spend far more time not only reflecting on what may impair the freedom of the church but also on how the freedom of the church may impair others.