Polly Seitz, left, and Karen Murphy exchange blessings at the river in Philippi where St. Lydia first met St. Paul. (FutureChurch)

For the past several days, I have been boning up on St. Paul's ministry in Greece as I prepare to lead a FutureChurch pilgrimage to early Christian sites where women had founding leadership roles.

Most Christians are completely unaware that women helped establish many of the earliest churches in Greece, Turkey and Rome. This is because church tradition always credits their founding to Paul.

Early Christ-followers circulated and preserved Paul's undisputed letters (circa 51-62 A.D.) and later, Luke's Acts of the Apostles (circa 80-90 A.D.), both of which chronicle Paul's missionary journeys in considerable — if sometimes differing — detail.

So it is understandable that later Christ followers thought Paul did it all. But he did not. In fact, Paul himself credits Prisca as his "coworker in Christ Jesus" (Romans 16: 3-5) and describes Euodia and Syntyche of Philippi as coworkers who "struggled beside me in the work of the gospel" (Philippians 4:3).

Paradoxically, no one would know about these early women leaders except for the patient piecing together of disparate facts by meticulous biblical scholars working with the very texts that chronicle (and sometimes lionize) Paul and other male leaders in the early church.

Acts identifies Lydia of Philippi as beginning the first house church in that city (Acts 16:6-40), and Paul's letter to the Philippians suggests that a disagreement between two women — Euodia and Syntyche — is threatening the unity of the church there (Philippians 4:2-3). According to well-known New Testament scholar, Sacred Heart Sr. Carolyn Osiek, Euodia and Syntyche were very likely among the episkopoi and diakonoi to whom Paul addresses his letter. (A reference, by the way, that Paul uses in no other greeting.)

In Thessaloniki and Berea, the Greek "leading women" supported Paul's mission even as the male synagogue members ran him out of town (see Acts 17:1-15).

Christianity seems to have held a special attraction for Gentile women. Women of status — whether from business (Lydia was a wealthy purple dye trader) or of societal prominence (Greek "leading women") — were especially drawn to the message of Jesus.

But why?

Recent research into ancient engravings at Philippi may shed light on this interesting question. In Ritual, Women and Philippi (Cascade Books, 2013), Jason T. Lamoreaux analyzed 140 etchings on the acropolis at Philippi. Ninety were dedicated to the Greek goddess Artemis (Roman goddess Diana). Lamoreaux suggests that since few other goddesses were in evidence at Philippi, the Artemis cult was a primary focus of women's religious lives in that city. He hypothesized that female worship of Artemis would therefore influence how women received Paul's letter to the Philippian church.

Advertisement

Known in Hellenist culture as the goddess of the hunt, Artemis was the daughter of Zeus and Leto, and the twin of Apollo. She remained a virgin, and women invoked her protection in pregnancy, childbirth and other female rites of passage such as puberty and marriage.

In the 90 archaeological reliefs at Philippi, Artemis was depicted 51 times as a huntress with a bow and arrow. In the androcentric imagination of ancient Greek medicine, the womb was viewed as a wandering animal. Artemis' arrow signified anchoring it and making it fertile. (Freud would have a hey-day with this. Seriously.) Seven times in the Philippi reliefs, the goddess is depicted with a sword slaying a deer, indicating the darker side of Artemis — namely her power to bring death.

Astronomically high maternal-infant death rates meant that ancient women had an intimate relationship with the prospect of dying. Religious ritual helped them deal with that. The acropolis reliefs contain images of gifts offered to Artemis in thanksgiving for a safe and successful childbirth: sandals, a mirror, a comb, a wool basket and spinning distaff.

If an infant or a woman died during childbirth, it was thought to be punishment from Artemis. Reliefs depicting her killing a stag may be commemorations of the death of a mother or her newborn. Artemis was feared until a woman survived childbirth.

Lamoureaux suggests that Philippian women heard the Christian message differently than men because Paul paints death as a positive and not as a punishment: "It is my eager expectation and hope that I will not be put to shame in any way, but that by my speaking with all boldness, Christ will be exalted now as always in my body, whether by life or by death. For to me, living is Christ and dying is gain" (Philippians 1:19-22).

One wonders what Lydia, a "God worshipper," and her female companions were about when Paul finds them at the "place of prayer" by the river. God-fearers were non-Jewish people who were interested in Judaism and hung around the local synagogue. But there was no synagogue at Philippi, or Paul, Timothy and Silas would have gone there for Sabbath worship as was their wont. Some scholars believe the Lukan author of Acts portrays Lydia as a "God worshipper" to clean up the disciples' religious gaffe.

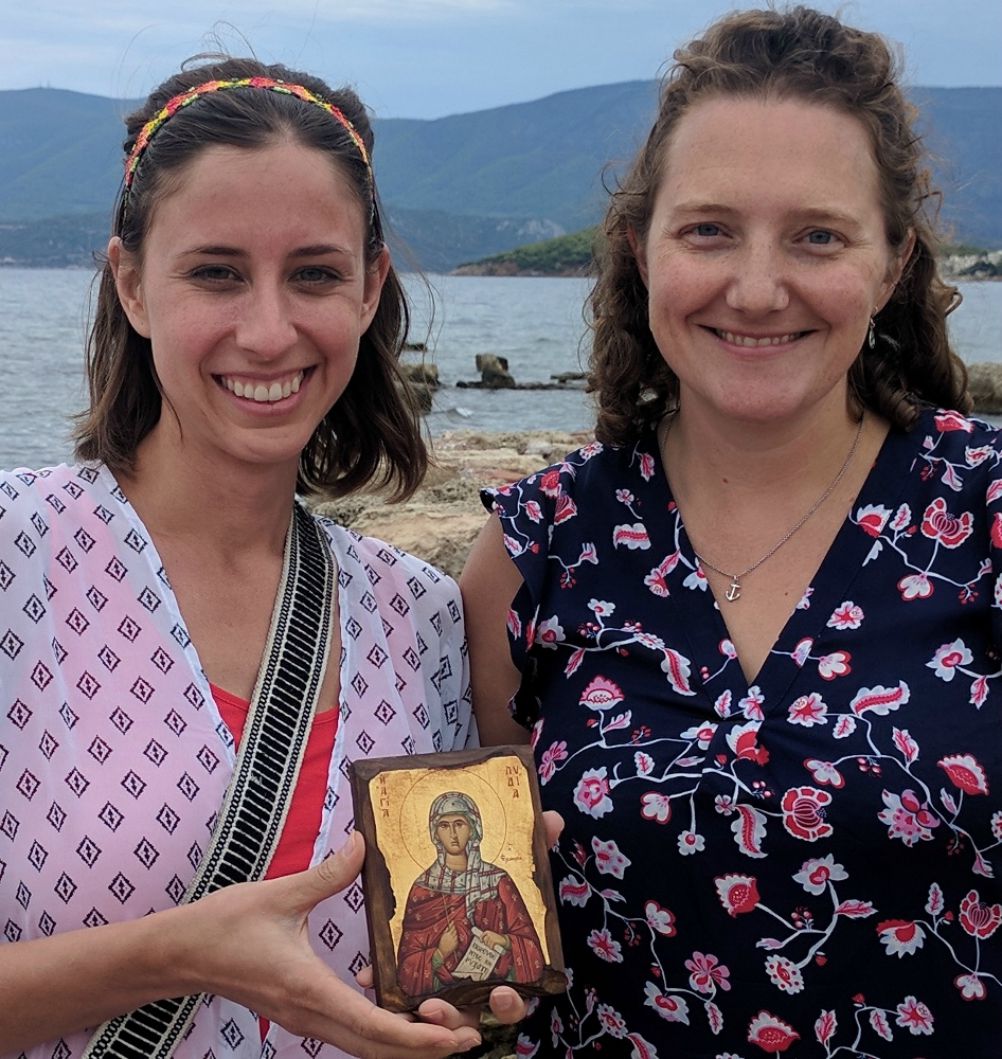

NCR Young Voices contributor Jenny Mertens, left, and FutureChurch board chair Jocelyn Collen hold an icon of Lydia of Philippi at the port of Cenchreae, hometown of Phoebe the "diakonos" in Romans 16:1-2. (FutureChurch)

After all, what was Paul doing crashing a woman's worship service?

What we do know is that Lydia "opened her heart" to the Gospel, was baptized herself, had her whole household baptized, and then invited Paul and his companions to stay at her home. Several weeks later before leaving town, Paul "encouraged the brothers and sisters" who are now meeting at her house (Acts 16:40).

Lydia started a church of Jesus-followers who believe death is not a negative.

Now that's a hopeful — if challenging — concept for all of us.

[St. Joseph Sr. Christine Schenk served urban families for 18 years as a nurse midwife before co-founding FutureChurch, where she served for 23 years. She holds master's degrees in nursing and theology.]

Editor's note: We can send you an email alert every time Christine Schenk's column, Simply Spirit, is posted. Go to this page and follow directions: Email alert sign-up.