The grave of Dorothy Day at Cemetery of the Resurrection in the Staten Island borough of New York, pictured Dec. 9, 2012 (CNS /Gregory A. Shemitz)

The Catholic Worker, the story goes, once hosted an extremely difficult perennial guest. No matter how much she received from the Worker's hospitality, it was never enough, and she let them know it. What could win over such a grasping hostility? Diamonds, of course. Upon receiving a valuable engagement ring from a donor, Dorothy promptly gave it to this guest. Scolded by coworkers who pleaded, not unreasonably, that the ring's value could have been put to better use, Dorothy defended her decision. The ring was the guest's to keep or sell, she told them. Did they think the poor had no need of beautiful things?

The story is characteristic of Dorothy Day and the movement she founded. There's the prodigal generosity that confounds common sense; there's the merciful irony in meeting voracity with abundance; there are the attempted reproaches and the neat rebuttal with echoes of a parable.

And it is characteristic of Kate Hennessy, Dorothy Day's granddaughter and the author of The World Will Be Saved by Beauty, to simultaneously appreciate the story as a sketch of her grandmother and to note that it is probably apocryphal.

"An Intimate Portrait of My Grandmother" is the subtitle of Hennessey's measured, warm-hearted account of Day's life, but its suggestion of a straightforward biography is not quite accurate. Hennessy's grandmother, the complicated, visionary, unstoppable Dorothy Day, is obviously the fulcrum on which the story turns. But the story itself is something much more meditative and complex: not the portrait of a single person but of a family tree. It's a portrait of the relationship between a mother, a daughter and a granddaughter, tangled and crisscrossed over time, never looking quite the same to any two of its participants.

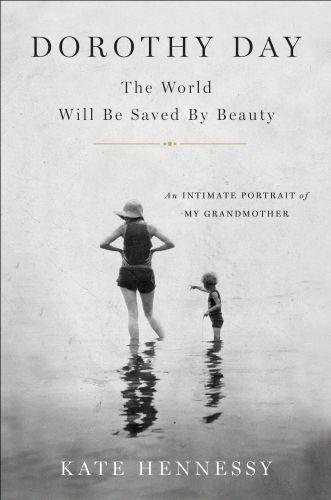

Cover of "Dorothy Day: The World Will Be Saved by Beauty: An Intimate Portrait of My Grandmother" by Kate Hennessy. (CNS)

Dorothy Day famously said that she didn't want to be called a saint. Despite this distaste for elevation, and by no machinations of her own, she very quickly leapfrogged over hagiography into something more like folklore. She was by all accounts a woman of an almost magical personal ability to burrow deep into life — a woman who walked the streets all night with Eugene O'Neill, and held a dying man in her arms when all her radical friends fled, a woman who lectured and bullied a would-be assailant cab driver until he meekly took her home.

But the folk hero treatment reduces her as surely as does the plaster statue approach. Too often, the picture we get of Dorothy is of a picturesque bohemian who, having outgrown the free-spirited life, made a clean and graceful transition into foundress, advocate and matriarch.

It's precisely this kind of enviable narrative that family memory is best equipped to puncture. And the image that emerges from Hennessey's book is of a much more particular and, in some ways, misfit personality. Dorothy comes across as impulsive to the point of recklessness. She boards a train to participate in a suffragette demonstration (her first imprisonment) more for lack of something else to do than long personal conviction. On the rebound from an unhappy love affair, she marries a recent acquaintance mostly, it seems, because he happened to ask. Shortly thereafter, she leaves him, early in the morning and without a word. She seems a natural drifter, and for most of her life that's how she lives: leaving school, leaving friends, never holding a job for more than a few months at a time.

But if Dorothy doesn't fit well into the romantic narratives of her life, neither do the recollections of her daughter Tamar fit into the more conservative criticisms. Until I read the book, I had assumed that the tension between Dorothy and her daughter Tamar lay in Dorothy's inevitable unavailability. But, in fact, what Tamar seems to have resented is not the Catholic Worker, but that Dorothy sent her away from it. Guilt stricken and heeding advice that the Worker was no place for a child, Dorothy frequently sent her daughter to convent boarding schools. Tamar could never seem to make Dorothy hear that she was not pining for a more conventional home but the home she actually knew and loved. Later, when Dorothy came under the influence of a dourly pious priest who believed that strict penitence, sobriety and self-denial were the only legitimate ways to serve God, Tamar felt she was losing her mother all over again.

Advertisement

These parental mistakes and childhood griefs do not fit into any neat narrative. They stem from the habits, quirks, virtues and sins particular to one stubborn, charismatic mother and one shy, tender-hearted daughter trying to find a place of her own. The story of the Catholic Worker is also a story of Dorothy's mistakes and failures, like domineering attempts to impose her own pieties on others and ill-judged farming communes that left little more than rotted fruit and bitter memories behind them.

And yet the Catholic Worker persists. It persists in nearly 250 communities around the world, clothing the naked, feeding the hungry, succoring the weary and lost, advocating for the least and lowest. Its successes are as much a product of Dorothy's difficult, misfit personality as are its failures.

None of this is to say that only a person like Dorothy can do God's work in the world. Quite the opposite: Seemingly unsuited for any kind of stable life, Dorothy offered herself as she was to God. She offered her specific gifts, and her sometimes abject failures, and continued offering them again and again, often without visible success or direction.

If Dorothy Day is ever canonized, it should be as the patroness of failures: of bums and burnouts and washed-ups and drifters and misfits and cranks. She provided service to them throughout her life and after her death. She was one of them herself. She offers a vision of what God can do in them and only them, if he is given space and trust to do his work.

[Clare Coffey lives in the Philadelphia area. She teaches kindergarten at a small Catholic school.]

Editor's note: We can send you an email alert every time a Young Voices column is posted to NCRonline.org. Go to this page and follow directions: Email alert sign-up.