Cardinal George Pell is pictured during an interview that aired April 14 on Sky News Australia. (CNS screenshot)

Throughout the unprecedented three-year saga of the arrest, conviction and ultimate acquittal of Australian Cardinal George Pell, there was no dearth of commentary on the case. Almost every single word of it was grossly uninformed.

Due to the judge's strict suppression order — put in place by agreement of both prosecution and defense to protect the cardinal's chances of being judged fairly — only the small group of people actually in the courtroom for the original 2018 proceedings really knew the full range of the facts.

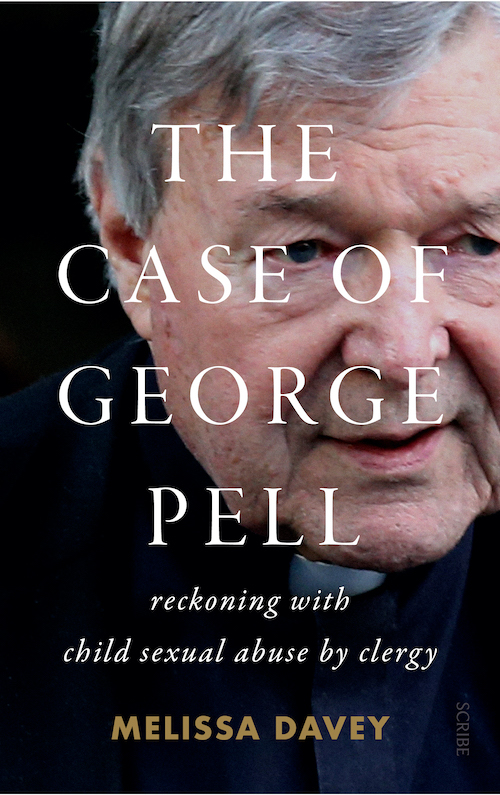

Cover art for "The Case of George Pell" (Scribe Publications)

And although some of the major details of the case came to light with the lifting of the order in February 2019, most of the drama has remained buried in undigested reams of court transcripts.

Now, for the first time, one of the only about eight journalists who was present to follow the blow-by-blow of the August-September 2018 mistrial and November-December 2018 retrial (and initial conviction) of Pell has published an exhaustive account of her experience.

Melissa Davey, Guardian Australia's Melbourne bureau chief, spent hour after hour and day after day in the back of courtroom 4.3 of the southeastern state of Victoria's County Court. Her resulting volume, The Case of George Pell: Reckoning with Child Sexual Abuse by Clergy, is an invaluable resource.

Part transcript, part diary of interviews with many of the trials' major players, part wider analysis of the devastating price victims pay in reporting abuse, Davey's volume pulls back the curtain on the once-secretive process — allowing readers a unique opportunity to evaluate the case against Pell, and his defense, for themselves.

Helpful in that endeavor is the way Davey draws the characters in intriguing and sympathetic ways, especially Judge Peter Kidd, who oversaw the initial trials as chief judge of the County Court of Victoria; chief prosecutor Mark Gibson; and Robert Richter, Pell's original high-profile defense lawyer.

Largely absent from the portraiture, of course, is Pell's alleged victim, whose identity was protected throughout the proceedings. The man claimed that as a choirboy in the late 1990s he and another boy had been sexually abused by Pell in the sacristy of Melbourne's St. Patrick's Cathedral.

Pell, who served as the archbishop of Melbourne from 1996 to 2001, strenuously denies the charges. The High Court of Australia, the country's final court of appeal, dismissed Pell's convictions on the charges in April, saying the jury in the 2018 retrial "ought to have entertained a doubt" as to the cardinal's guilt.

Advertisement

The journalists who attended the 2018 court proceedings were not allowed to be present in the courtroom for the alleged victim's testimony and cross-examination. Davey, however, sharply rebuts commentators, such as Jesuit Fr. Frank Brennan, who claimed the man presented "confused" testimony.

"In the conversations that occurred between journalists and lawyers in the corridors of the courthouse, I never heard anyone who’d been present during the complainant’s testimony say that he had performed badly," states Davey. "Instead, the complainant was described as 'compelling' and 'honest.' "

At points, Davey's book is somewhat laborious reading — especially as she repeats bits of testimony through Pell's mistrial, retrial and appeal.

But it is also something of a send-up of the old-school journalistic craft: hunching over a laptop in the back of a room, typing as best you can — and returning later to review physical copies of the transcripts, under the watchful eye of a clerk instructed never to leave the documents unattended.

Understandably, Davey reserves some of her strongest language for journalists and media outlets that did not attend the 2018 proceedings but yet decided to publish information about Pell's conviction in violation of the strict suppression order.

Kidd had originally imposed the order because Pell was meant to be the subject of a second trial, later scuttled, about his alleged conduct with boys at a swimming pool in the late 1970s. The judge feared that if the first trial attracted a media circus, selecting an impartial jury for the second trial would be nearly impossible.

Davey makes clear that at the time of the order's imposition, "no media organizations opposed the move." The journalists in the room, Davey says, "respected the parties — including the judge, the prosecution, the defense, and the complainant."

'We were there to report on the facts, but only when doing so would no longer jeopardize the administration of justice. Other reporters, in their fight to be first, did not care about this.'

—Melissa Davey

Coming under particularly fiery condemnation is Sky News Australia host Andrew Bolt, who in a February 2019 column said he had seen "overwhelming evidence" of Pell's innocence. Pell would later grant Bolt an extended video interview, the cardinal's first upon release from prison.

"Bolt had not been present to hear any of the evidence," writes Davey, before adding: "There is no evidence that Andrew Bolt is more capable than a jury of determining the guilt or innocence of a person charged with serious criminal offences."

As for the jury's original verdict, Davey leaves the reader with a very uncomfortable question in her chapter on Pell's ultimate acquittal. She quotes lawyer and La Trobe University law professor Gideon Boas:

"I've heard it said a lot in this case, 'How could the jury get it so wrong when the High Court decided unanimously it was an unreasonable verdict?' My response is: 'what's to say the High Court had it right?' "

[Joshua J. McElwee is NCR Vatican correspondent and international news editor. His email address is jmcelwee@ncronline.org. Follow him on Twitter: @joshjmac.]