Two girls perform in the variety show at the Sept. 17-19 Sugar Creek Catholic Worker gathering. Since the late 1970s, the annual event in Iowa's Jackson County has brought together members of the dozens of Catholic Worker communities throughout the Midwest. (Photo courtesy Mary Farrell)

"You forgot Football Mary!" shouted a white-bearded man at the back of the crowd.

"Huh?" I breathed confusedly into the microphone. I'd just finished emceeing the two-hour outdoor variety show that is a centerpiece of the Sugar Creek gathering of Catholic Workers at a rural church and retreat center at the edge of Iowa's Jackson County.

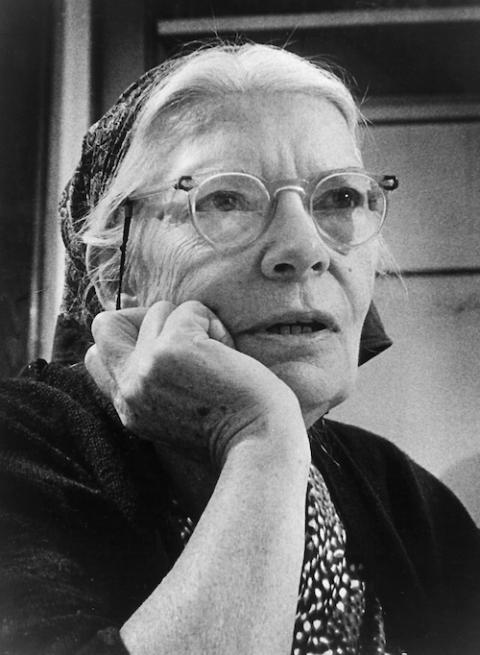

Held annually since the late 1970s, the gathering brings together members of the dozens of Catholic Worker communities throughout the Midwest for shared meals, roundtable discussions and fun. Inspired by the vision of Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin, who founded the first community in New York in 1933, Workers typically spend their days serving their local community or witnessing against inequality or injustice.

Due to the coronavirus pandemic, the Sugar Creek gathering did not take place in 2020. But Sept. 17-19, a group of some 80 Catholic Workers from Detroit to Kansas were finally able to gather. Wanting to make myself useful as a first-time attendee, I'd offered to host the variety show.

"The best act gets to take Football Mary home for a year," the bearded man explained, gesturing to a stuffed toy Virgin Mary with a football attached. I then learned that this joke was an answer to the University of Notre Dame's "Touchdown Jesus," the famed Word of Life Mural overlooking the university's football field. "We vote by applause."

Advertisement

"Who's the judge?" I asked.

"You are!" several spectators called in unison. "And you'll be wrong!" the bearded man added. After reading off all the acts that had just graced the stage — skits, music, poetry, storytelling and acrobatics accompanied by pianica (a miniature keyboard powered by breath) — I gauged the crowd's enthusiasm and relied on my own biases to offer the prize to Alice and Tressa, two preteen dancers from the Bloomington, Indiana, Christian Radicals Catholic Worker.

Music and dancing ensued. While the pandemic cast a shadow of caution over the gathering — most events were outdoors and masks required inside — Catholic Workers were eager to connect.

"Something was lost when we couldn't hold this event last year," said Eric Anglada of St. Isidore Catholic Worker Farm in Cuba City, Wisconsin. Anglada has attended Sugar Creek since 2003 and has helped organize the event since 2015. "So many of us come needing to recharge because we are in isolated communities. Sugar Creek provides a chance to talk among people who know what we are experiencing. To some people it feels like a family reunion because so many of us know each other from previous gatherings, but we are also welcoming to new people."

He added: "Catholic Workers can get burned out because they feel like their justice work is not fully understood by the wider community where they live, so they thrive in a setting where they can come together and have an unspoken understanding."

For some, the normal challenges of living in community and working the land in rural areas or serving those living in poverty in urban houses of hospitality have intensified during the pandemic.

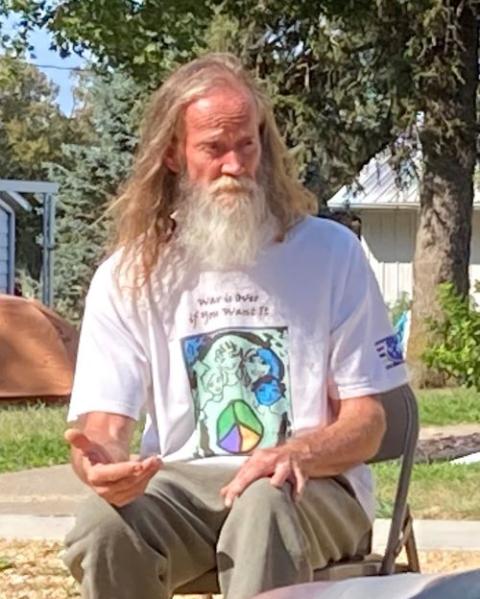

Mike Miles of Anathoth Catholic Worker Farm in Wisconsin leads a roundtable discussion during the Sept. 17-19 Sugar Creek Catholic Worker gathering. (Photo courtesy Mary Farrell)

Steve Jacobs, who has served at St. Francis Catholic Worker in Columbia, Missouri, for 31 years, has been frustrated by vaccine hesitancy among those experiencing homelessness in his community. "Right now we have six live-in Catholic workers and only have two guests because of COVID. We've had to turn a lot of people away due to health protocols," he said, mentioning that while they did manage to host a vaccine drive for 20 people experiencing homelessness, many more have refused.

"Most of the people we are seeing are heavily into addictions," Jacobs added. "I see drug transactions in the city park from my bedroom window. I can't say the pandemic has made rates of drug use higher, but when people hit bottom and want help, it's difficult — the pandemic has made that worse."

Despite these obstacles, several new Catholic Worker communities have started or been resurrected in such places as Detroit and Ames, Iowa.

Kimberly Hunter is a leader at the Eliza B. Conley House in Kansas City, Kansas, which opened in January with a specific mission of providing housing and support for women and children of color.

"We have eleven people now, but we've had six others since the beginning of the year, including a family of five who'd recently moved to the U.S. and been wrongfully evicted by their landlord," Hunter explained. "We're committed to providing safe, stable, affordable housing for people of color, especially activists, if they need to rest or pursue their own goals."

Hunter, who is in her 30s and has a Mennonite background, first encountered the Catholic Worker Movement in 2008 and came to Sugar Creek eager to learn from experienced Workers.

"My father is a pastor, and I grew up in a house where hypocrisy was not an option. Whatever you say you believe, your life has to match that," Hunger said. "When I learned how white-led U.S. Christianity was a part of military and oppression, it was shocking to me because I hadn't realized it. At first I thought maybe there wasn't a place for me in Christianity, but progressive Mennonites and Catholic Workers modeled a different way of life for me."

Anti-racism and decolonization, along with environmental justice, were major themes running through Saturday's round-table discussions, especially in the wake of ongoing public discussions about racism within the Catholic Worker Movement and Catholic Workers' involvement in anti-pipeline activism. One discussion revolved around Worker involvement in movements supporting police abolition.

"White guilt has animated decisions and been unhelpful. People have good intentions but can do more harm when not doing the work of building relationship," Abby Rampone of Chicago's Su Casa Catholic Worker said during one discussion. "The role we let guilt play in our decision-making can become toxic. We need to be prayerful, intentional and relational."

Dorothy Day, co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement, pictured in an undated photo (CNS/Courtesy of the Milwaukee Journal)

One major activity of the Sugar Creek gathering is planning a spring resistance retreat, when people travel to a local Catholic Worker community to support them in a struggle, often involving a direct-action protest or witness. While the action for Spring 2022 is still undecided, Workers plan to support an urban struggle either against gentrification or for police abolition.

My involvement with the Catholic Worker Movement has been peripheral, but ongoing. I volunteered with a Catholic Worker community in Dubuque, Iowa, from 2016 through 2018 and have provided temporary free housing to three young people living in poverty since 2018.

While I hesitate to call myself a Catholic Worker because I do not espouse the voluntary poverty characteristic of the movement, I am driven by many aspects of the founders' ethos, particularly personalism, hospitality and the idea that direct charity and justice advocacy are deeply interwoven.

Sugar Creek left me with a deepened awareness of the intersections between different justice issues and joy in community. After I served as an emcee for the variety show, Anglada said that my leadership role at the event despite being a newcomer was "anarchism in action."

We need to be prayerful, intentional and relational."

— Abby Rampone

On Sunday morning Sept. 19, the groups from Chicago led a liturgy in which we shared griefs and celebrated joys through prayer and song. As communities packed up their tents and said their goodbyes, a few paused to reflect on the significance of the gathering.

"We had a much better turnout than expected," Anglada said at breakfast, adding that he is heartened by the direction of the movement. "Catholic Workers are reflecting an ongoing emphasis on stewardship of the land, decolonization and anti-racism work. Those focal points are not new, but they are deepening."

"After Dorothy Day died in the 1980s, some people thought the movement would die with her, but instead it has tripled in size," added Mike Miles, who with his wife Barb Kass practices regenerative agriculture at Anathoth Catholic Worker Farm near Luck, Wisconsin. "It is delightful to see how the message of the Catholic Worker Movement continues to attract new people."