William Kelly, left, and artist Ricardo Abaunza, with artwork "Dialogue with Guernica" in Guernica, Spain, in 2007 (Courtesy of William Kelly)

During a meeting with William Kelly decades ago in his studio at a small college in Pennsylvania, he held up a large canvas, fully the size from top to bottom of an adult and nearly as wide, upon which was painted a nude figure. It seemed a large piece at the time, but spare in context, a discrete moment, a single anonymous figure in an awkward and confined space.

William Kelly at the State Library of Victoria, in front of his project "Peace or War/The Big Picture," in Melbourne, Australia (Courtesy of William Kelly)

It was, for its part, one step toward the artist’s latest project, a print 42 feet long and more than 5 feet wide, titled “Peace or War/The Big Picture.” It is a monumental work not only in size but as a rich narrative of images, raw figurative work and words. It was suspended from October to December 2016 in the La Trobe Reading Room at the State Library of Victoria in Melbourne, Australia.

More than square footage and distance separate the piece he displayed in his studio in the early 1970s and the one completed in Australia. Along the way, he and his art underwent a significant change, an evolution from untitled pieces solving aesthetic and formal questions to less ambiguous and certainly grander efforts at pushing the conversation around nonviolence and peacemaking.

Trained at the Philadelphia College of Art (now the University of the Arts) and the National Gallery School in Melbourne, Kelly was also a Fulbright scholar (he first visited Australia in 1968 under that designation) and dean of the Victorian College of the Arts in Melbourne from 1975-1982. He is internationally known and exhibited as a humanist and human-rights advocate in a discipline that can be ill at ease with such close identification with a cause or point of view.

Kelly has exhibited in 20 countries and been a lecturer or visiting artist at places as diverse as Oxford, Cambridge and Yale, as well as the Pennsylvania Prison System and schools in India, Italy and the Republic of Georgia.

His work is represented in more than 40 public and corporate collections. He is founder of the Archive of Humanist Art, a collection of work from around the world that addresses human rights and social justice concerns. His social aims also have been publicly labeled by at least one art critic as “naive,” a label to which he responded with gratitude.

That meeting back in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, was the beginning of a friendship and correspondence that has lasted more than 40 years. Most of the time it has been a friendship at a great distance, since he and his family (there are four grown children) moved to Australia shortly after we met. The artist, now 74, has returned to the United States at times to lecture and work on peace projects. We often met on those occasions and discussed whatever ventures were underway. I visited him in Australia in 2014 and conducted interviews there about the progression of his work and again earlier this spring during a stopover he made in New York.

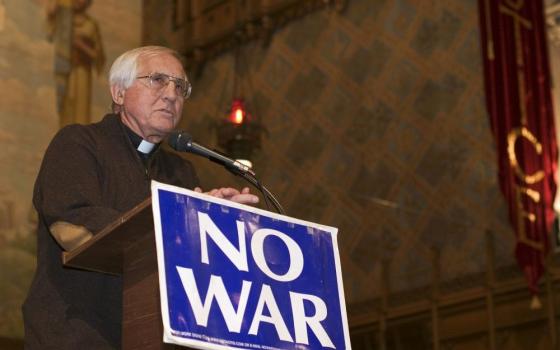

William Kelly (NCR photo/Tom Roberts)

Kelly is endlessly patient with the questions of a non-artist intrigued with his turn of life. He and his wife, Veronica, a mosaic artist and lifelong activist in local matters of the environment and issues involving children, have lived for the past 17 years in rural Australia. There is something mildly Franciscan about him (he would demur but the saint from Assisi is long a favorite historic figure) in his strong aversion to violence and unambiguous concern for the earth. Maybe, too, it is the unchanging khaki, a kind of habit he wears — work shirt with pockets and the same color pants, someone heading for the factory — that has been the only outfit I’ve seen him in over the decades. He did, in fact, once labor in factories as a steelworker and welder.

He skates along a thin edge bordering religious experience (heavily influenced in his peace work by people like Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan and Mahatma Gandhi) without ever falling in. One can detect the same attitude toward a kind of utopianism to which he never gives full assent. In each case appropriating symbols and ideas and, as he has put it, making marks here and there or painting things that he cares deeply about.

Painted on that canvas years ago was a figure lying on a floor, a bit of baseboard and an electric outlet, as I recall, the only points of reference holding her in place in a well-defined space. Without warning, Kelly turned the canvas 90 degrees. I nearly went sideways with it. She would stay in place; there was no top or bottom to the scene, no up or down.

If his art at one point conveyed a sense of unease and confinement, another hard edge of reality, random violence, later demanded his attention and turned his focus to peacemaking.

Those earlier paintings and prints, some of humans, some of blocks and children’s toys, one set of large prints executed dramatically on black against the outline of the Cologne Cathedral spires, "were trying to get at how uncomfortable these spaces are that we build. And how awkward, even though the figure might be beautiful, even though the context is incredibly simple. Why is it that we can get lost in our world by doing simple, straightforward things, but they get more complicated and give us unease?" Kelly said in the most recent conversation.

"Veronica," by William Kelly, 1983 (Courtesy of William Kelly)

"The philosophical issue with all of those figures … humans, children’s blocks and balls and things like that, the deal for me was that we build these spaces — the city, the room, the house, whatever — in ways that we find that they are hard to live in. They have boundaries; they have edges. They are spaces that confine us."

If his art at one point conveyed a sense of unease and confinement, another hard edge of reality, random violence, later demanded his attention and turned his focus to peacemaking. On Aug. 9, 1987, a 19-year-old disgruntled former cadet in the Australian army began firing an automatic weapon at civilians in a quiet suburb of Melbourne, killing seven and wounding 19. What became known as the Hoddle Street Massacre was a defining moment for Kelly, a professed pacifist.

From the streets to the studio

A life of art and pacifism would have been an unlikely prediction for the kid who hung out on street corners from the age of 7 around South Park Avenue in Lackawanna, New York. The city in the 1950s, a quickly expanding center of steel making, attracted large immigrant populations to what appeared to be endless job opportunities. He recalls that his neighbors included a displaced family that had escaped Hungary, Italians, Lebanese, a Swede, other Eastern Europeans, "and us, Shanty Irish."

It was a poor neighborhood where hanging out on the streets meant taking up with youth gangs and the fighting that went with them. He has some knife-wound scars to show for it. But there was another side of life for Kelly that he didn't share with his street buddies.

"I read incessantly. I virtually read my way through the Lackawanna Public Library, starting with kids' books and through to U.S. literature when I was around 12-14 years old," he said. "All of this was a journey of discovery."

Before he began high school, Kelly's family moved to an apartment two miles away in south Buffalo, a more conventional, working class environment. The distance from his old neighborhood, he said, "gave me some room to explore." No longer on the street corner, he began to work after school and weekends at a local drug store. He kept some of the money, the rest went to his family.

Reading continued to be his "escape hatch," a passageway into "other worlds out there. I knew at 17 or 18 that I would somehow try to go exploring in those other worlds."

He began drawing on his own and writing poetry, took night classes in writing and theater and art, the latter a disappointment because it turned out to be a course in "sign writing."

Then came the serendipitous moment that produced one of life's big road signs. He went one day to the north side of Buffalo but couldn't figure out how to get back to the south side.

"I didn't know which bus to take to get back downtown. I ended up in front of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, where I had never been before," he said. "I went in to ask the guy at the desk for directions. On the wall was the de Chirico. I immediately was drawn to the idea that pictures could carry mystery, meaning, poetry. Literally my first time in any gallery, my first experience of a painter's painting. It was a pivotal point."

The painting he saw was Giorgio de Chirico's "The Anguish of Departure," a somewhat enigmatic piece, described as metaphysical art, that evocatively uses ordinary items in a sparse landscape.

Soon after, organizing his Saturday mornings so he could be off work, Kelly began taking art classes at the museum, and decided to apply to art school.

William Kelly, with prints from "The Peace Project," in 1994 at Boston (Courtesy of William Kelly)

Art as advocacy

If, in the instance of Kelly, art imitates life, one way is the manner in which the advocate is perceived, particularly the pacifist and activist working on behalf of nonviolence. In ordinary life, who looks askance at the general, chest full of medals and ribbons, state-bestowed honors, and asks, "Is he for real?"

It is not asked by the wider culture in the same way or as frequently as it might be asked of the pacifist, with no ribbons, no state honors and far fewer resources than those available the general. There remains something unreal, or at least impractical, about the pacifist.

The questions I pressed, certainly not original, were: When does art that has turned to advocacy, or a cause, cease to be art? When does the real thing become something else? At what point does the look from others become skeptical?

The answers telescope outward from simple to complex.

"I just paint pictures," he begins. "I just make pictures about things that are important to me. Sometimes I make pictures about kids and grandkids. The deal is that you do these things you believe in and then someone is interested in them as art and as content."

Of course, it is not all that simple. He thinks, for instance, that the division is, in a sense, a false dualism, and that writers have an easier time navigating around such polarities.

William Kelly (NCR photo/Tom Roberts)

He raises Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse Five as an example. "Good literature, right? Good content, overall an antiwar statement. But I don't think that he wrote that to be a polemic about war. It was a story that he had in him that had to get out. And it was following his view of the world and his ideas and attitudes."

Does he really believe Vonnegut wrote the book with a kind of neutral view of war? That somehow the antiwar element just happened? "No, no. He was passionately against war, as am I. But what he is, is a writer, and he's writing a book, and he's got this story, and the story reflects his view that he is passionately against war."

In an earlier conversation, he described it another way.

"There have been artists who have said that their art is separate from their life, that their art is one thing and their political, social and other views are entirely different and they don't interact — they don't have an interface. And there are artists for whom that relationship between art and life is much closer, and that's where I sit.

"When I think to do anything, I can only do things that reflect subject matter or topics or things that I'm interested in and passionate about. So, do they have an ethical concern? Yes. How are they expressed? They're expressed through art. Is there then this for me — an axiomatic relationship between art and ethics? Yes, absolutely."

He wants that relationship to be unambiguous in his work.

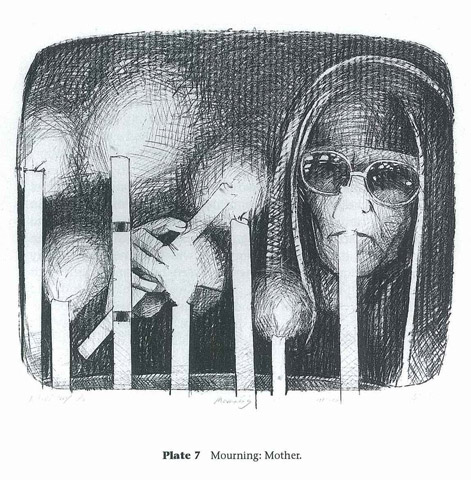

"Kelly became more obviously committed to social issues, to a wider audience at least (those involved with him in any capacity know how unique an individual he is, and that social commitment is central to his work) when he responded to a massacre in Melbourne — the tragic killing of seven people and the wounding of 19 people in Hoddle Street — with a suite of prints and a book dedicated to the peace process," wrote Janet McKenzie in a 2008 article in the publication Studio International, under the title "Artist as Peacemaker."

Wrote art historian Jenny Zimmer for the catalogue of a Kelly exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in Melbourne: "His processes are interrogative, non-judgmental, juxtaposed, discontinuous. He offers a vast and complex narrative capable of many useful readings: a lively interaction between timeless moral philosophy and contemporary thought."

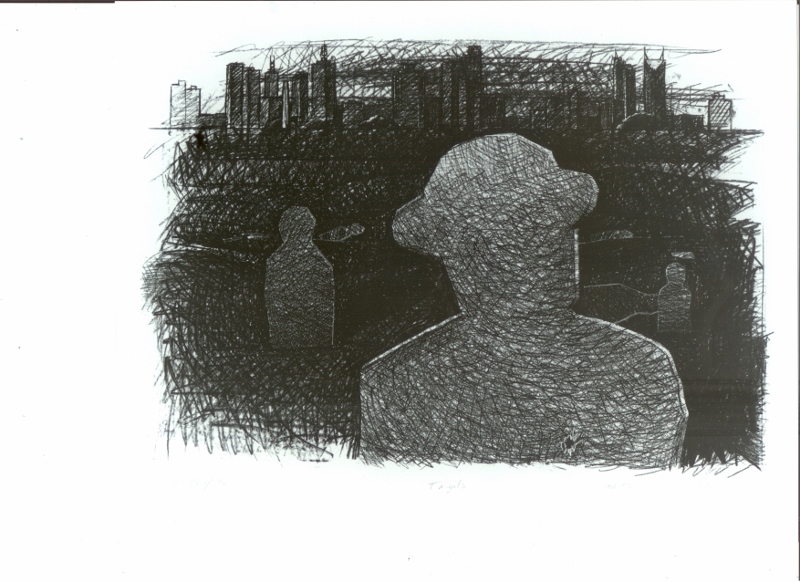

"Targets" print from "The Peace Project," by William Kelly (Courtesy of William Kelly)

The interrogative (or dialogic) characteristic of his art is quite apparent in the 80 works making up "The Peace Project," his reaction to the Hoddle Street Massacre. The art resulted from five years of interviews and discussions with people involved in all phases of the tragedy — from witnesses to forensic specialists.

Nothing screams a cause in this collection — it is a subdued narrative of everyday figures and objects that, in one way or another, were altered or rearranged by a burst of violence on a quiet street. The pieces, standing on their own as they do, nonetheless comprise in concert a narrative, employing the not uncommon storytelling device of exploiting a particular incident for its universal application.

"Mother Mourning," a print by Kelly from "The Peace Project" (Courtesy of William Kelly)

Some reviewers and commentators have placed him in line with such notable public moralists as Leo Tolstoy, Hermann Hesse, and Gandhi, representing in various ways no small struggles with religion. In current parlance, Kelly might be considered an artist for the "nones," those who have slipped the constraints of old denominational and institutional ties. Asked if he ever thought of himself as dealing with religious content, he said, "No. When I deal with something that might have a reference to religious content, or what's seen as religious content, it doesn't feel religious to me."

"St. Peter," screenprint by William Kelly (Courtesy of William Kelly)

For instance, he said, if he were to do a depiction of Christ's crucifixion, "the way I approach it is that I'm not thinking so much of this religious story, but of capital punishment." He said he's asked the question in class, "What's the most prominent image to do with capital punishment that you know of?" And Andy Warhol's "Electric Chair," is often the answer.

"And I say, 'Well what about the crucifixion of Christ?' People tend not to think of that as capital punishment because it's a religious image. … And with the sculpture that I showed you of a fairly poor image of Veronica wiping the face of Jesus — for me that's an image of compassion. It's a woman who saw somebody suffering and said, 'What can I do? This is the small act that I can do. I will do this.' Was it a religious act? I don't know."

Kelly was also strongly affected by Picasso's "Guernica," a massive and striking antiwar mural done in 1937, depicting the effects earlier the same year of a saturation bombing by the Nazis of the city of Guernica, Spain, during the Spanish Civil War.

Since the late 1990s, Kelly has collaborated with two Basque artists, Ricardo Abaunza and Alex Carrascosa, as well as three local institutions in Guernica on an initiative to show the relationship between art and peace. In 2001, he designed a stirring installation, "Plaza of Fire and Light: Place of Peacemakers," for Guernica's civic plaza, in commemoration of the bombing. He also has work permanently displayed in the city. The installation there was one of several major public installations he has designed, several of them permanent, including "The Tower: A Monument to Migration and Aspirations," that gives a wide view of wetlands in southern Australia.

"Plaza of Fire and Light: Place of Peacemakers," an installation for the civic plaza of Guernica, Spain (Courtesy of William Kelly)

In an essay accompanying the print "Peace or War/The Big Picture," Vincent Alessi of La Trobe University in Melbourne, writes that Kelly "does not stand in the corner with a loudspeaker shouting and directing his world view. He is more intelligent and poetic than that." He said the artist "asks us to stop, look, think consider and act not via direction but rather by dialogue."

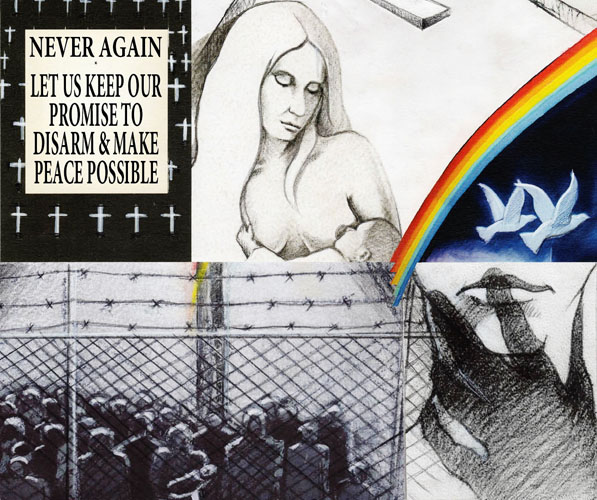

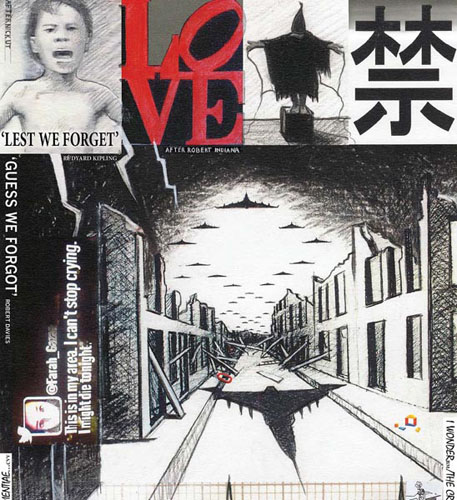

Section from "Peace or War/The Big Picture," by William Kelly (Courtesy of William Kelly)

There is a great deal to talk about in the depictions of the four-story work — a collection of images and words beginning at top with the most ordinary scene of everyday life, a flock of birds overhead, and cascading down to scenes of destruction, as the birds mutate into bomber squadrons. Bits of hope are expressed in color breaking through the gray tones of war, and it ends in a construction that gives hope. There is no mistaking the up or down of this work, which rests solidly on a foundation comprising names of peacemakers and advocates of social justice from every corner of human activity.

Section from "Peace or War/The Big Picture," by William Kelly, including a drawing of the photo of Phan Thi Kim Phuc by Nick Ut (Courtesy of William Kelly)

Tourists at the civic plaza of Guernica, Spain (Courtesy of William Kelly)

Quiet as his advocacy may be — marked by a detachment that at times approaches journalistic, as well as the humor and humanity of children's toys — he wants to be understood. Toward that end, he has been organizing an exhibition for the city of Melbourne to open Nov. 9 titled "Peace Not War/Art that Takes a Stand," with works by Australian and international artists. He is also the subject of a documentary underway titled "Kelly's Big Picture: Can Art Stop a Bullet?" His answer to that, by the way, is, "No, but maybe it can stop a bullet from being fired."

"I don't want it reinterpreted in 50 years, 100 years or 500 years, if the world lasts that long, or the art does," he said during a conversation in a small beach apartment outside of Melbourne. He doesn't want one observer to say it's an antiwar statement, while another construes it as pro-war.

"I want them to know that it's made by somebody who believes that we have the capacity to change things for the better. I want that to be known, and that's the framework in which all the work exists."

[Tom Roberts is NCR editor-at-large. His email address is troberts@ncronline.org.]

Advertisement