Michael Gandolfini, left, as Tony Soprano and Alessandro Nivola as Dickie Moltisanti in "The Many Saints of Newark" (HBO Max)

A long, tough summer is finally about to end for Bob Cascella and many other parishioners at St. Lucy's Church on Seventh Avenue in Newark, New Jersey. The parish's annual feast of St. Gerard — now in its 122nd year — will be held Oct. 15-17 and is expected to draw thousands to this historic Italian-American church. The celebration comes after 18 months of COVID-19 challenges, as well as a Memorial Day fire that destroyed St. Lucy's rectory.

"Everybody's been talking about [the feast]," said Cascella, a longtime parishioner, who is also the founder and president of the Newark First Ward Heritage and Cultural Society.

But St. Gerard Majella — an 18th-century Italian Redemptorist, and the patron saint to expectant mothers — is not the only Garden State saint people are talking about these days.

The highly anticipated movie "The Many Saints of Newark," which premiered Oct. 1, tells fictional mobster Tony Soprano's coming-of-age story amid the backdrop of the 1967 Newark riots.

David Chase, creator of "The Sopranos" and the writer and director of "Many Saints," has a particularly unique perspective on the religious background of the Italian American characters in both the series and film.

"Their Catholicism was always interesting to me... [and] as a storyteller I'm certainly interested in spirituality," Chase told NCR during a recent interview.

A scene from the movie "The Many Saints of Newark" (HBO Max)

Chase, who is Italian and was raised in a Baptist family, didn't have a great experience at the Baptist school his parents sent him to.

"I never got to go to confession, or go to church where they were swinging incense around. ... My mother made a big façade of being religiously concerned. And father considered himself an atheist. But they made me go to Sunday school, where I learned, among other things ... that God doesn't like Catholics because they drink during their church services."

His parents did once give him a very meaningful gift.

"[They] got me a World Book Encyclopedia. ... And one day I looked up art. A-R-T. And I saw a picture of Caravaggio, and all these other great works ... and I began to realize I like art. I like music and movies. ... It was never my goal to be a storyteller."

And though Chase has had a long career in TV, most of his influences were in other areas.

"The Beatles happened, and then Bob Dylan happened, and the Rolling Stones. I wanted to be in a rock-n-roll band."

But Chase adds: "One great thing about [those musicians] is they do tell stories."

David Chase (Wikimedia Commons/U.S. Embassy Dublin)

In a scene early in the new film, Tony's uncle, Dickie Moltisanti (Alessandro Nivola), calls him over, saying, "There's something you gotta see," before he and his pals gaze at the flames and smoke rising above Belmont Avenue. Young Tony himself, played by the late James Gandolfini's son, Michael, stares out his bedroom window. Like many Americans that year, he is somewhere between transfixed and oblivious.

And for all the blood and bullets flying in "Many Saints," at its center is Uncle Dickie's struggle to do what he calls "something good." He even seeks penitential guidance from an imprisoned, Buddhist-quoting, Miles-Davis-loving uncle.

"There is something confessional about those scenes," Chase says before wondering aloud: "Is Dickie really that interested in doing good deeds ... when he's there moping and whining? I don't know. Maybe. Psychopaths are able to convince themselves of all sorts of things."

These days, as Catholic activists and a deeply divided nation continue to confront a wide range of moral and social justice questions, "The Many Saints of Newark" highlights the role 20th-century Catholic leaders played fighting poverty and supporting immigrant communities while also capturing the unintended consequences of ambitious federal building programs that were designed to improve cities like Newark.

Additionally, the film calls attention to the ways the Italian diaspora and African American Great Migration collided.

The Italians gangsters may finally be able to drive flashy cars, but they park them in tight driveways next to humble homes, while the Old World rests heavily on their language and customs. As more ambitious African Americans make their way to Jersey from the south, there are only so many slices of underworld pie to fight over.

For all the violence and hate that ensues, it's worth noting that the film's main conflict takes place between the Moltisanti clan (hence the title) and a former member of a crew called "The Black Saints."

These days, strolling between Sixth and Seventh avenues in Newark, the lush greenery of Branch Brook Park gives way to the imposing twin spires of the Cathedral Basilica of the Sacred Heart — the seat of the Newark Archdiocese and the fifth largest cathedral in North America.

Sharp-eyed viewers of the opening credits of "The Sopranos" catch a glimpse of the Newark basilica between the Pulaski Skyway and Satriale's Pork Store.

Two blocks over, at Ruggiero Plaza, is St. Lucy's, designated by the U.S. National Conference of Catholic Bishops in 1977 as the national shrine to St. Gerard.

"He really is a miracle worker. There are so many stories," St. Lucy's pastor Fr. Paul Donohue told NCR during a recent visit. Father Paul adds that people seeking St. Gerard's intercession contact St. Lucy's from all around the world, including North America, Asia and Europe.

A native of Lorain, Ohio, west of Cleveland, Father Paul has served with the Comboni missionaries in Ireland, Rome and elsewhere, before moving to St. Lucy's over a decade ago.

St. Lucy's Church in Newark, New Jersey (Wikimedia Commons/Jim.henderson)

"The history of a place is always important to me ... wherever I've gone," adds Donohue.

The original St. Lucy's church, he notes, was built in 1891, months before Ellis Island opened in the harbor just 10 miles to the east, signaling a new phase in U.S. immigration.

St. Lucy's "was the First Ward's spiritual axis and remains its most enduring institution," Michael Immerso writes in Newark's Little Italy: The Vanished First Ward. In 1890, after 11 Italian immigrants were lynched in New Orleans amid a murder investigation, The New York Times labeled the victims "descendants of bandits and assassins, who have transported to this country the lawless passions, the cut-throat practices, and the oath-bound societies of their native country."

The current St. Lucy's building was completed in 1925, the same year 30,000 anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic KKK members marched on Washington.

Amid all of this adversity, especially once the Great Depression struck, St. Lucy's was a sanctuary.

The interior of St. Lucy's Church in Newark, New Jersey (Wikimedia Commons/Bestbudbrian)

Upon the 1933 death of revered pastor Msgr. Joseph Perotti, his assistant, Sicilian-born Gaetano Ruggiero, became "the preeminent figure in the community for more than three decades," according to Immerso.

A "kind, gregarious leader," Ruggiero "always seemed to be visiting a sick widow, chatting with schoolchildren, [or] giving the blessing at a social-club dinner," Brad R. Tuttle writes in How Newark Became Newark: The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of an American City.

Such memories make it easy to forget that life in the First Ward could be hard, and the surrounding area was in constant flux. Many children and grandchildren of immigrants moved to shiny new suburban homes.

Those who stayed found jobs in the school system, police or fire departments, and even City Hall — symbols of advancement in the New World.

Meanwhile, there was another wave of new arrivals, not from Sicily or Palermo, but Selma and Macon. African Americans were fleeing the violence and terror of Jim Crow and the KKK and seeking work in Northern cities like Chicago, Detroit, Pittsburgh — and Newark.

Many were "nervous about missing their [New York] stop, some got off prematurely, and, it is said, that is how Newark gained a good portion of its black population," Isabel Wilkerson writes in her best-selling book The Warmth of Other Suns.

Advertisement

After World War II, "slum clearance" became a catchall term to, at least theoretically, provide more and better living conditions to working-class migrants.

Ruggiero, as one of the community's most vocal cheerleaders, initially supported proposals for new public housing in the First Ward. But in Newark, and other U.S. cities, these ambitious plans failed to take into account many complex factors, including decades of systemic racism. After a new First Ward housing project was unveiled in October 1956, Ruggiero and other civic leaders became vocal opponents. "By the time he fully understood the enormity of the project, it was too late," Ruggiero's successor, Msgr. Joseph Granato, once said.

Meanwhile, African Americans kept arriving from the South, including John Smith, who came to Jersey from Warthen, Georgia, with his parents, only to be arrested during the 1967 riot. The wants and needs of the African American community were similar to those arriving from Italy a few decades earlier. But there was now a raging housing debate in heavily segregated Newark and an emboldened civil rights movement across the U.S., both of which are depicted vividly in "The Many Saints of Newark."

Amid all of this, in 1966, Ruggiero died.

A few months later, after Smith's arrest — following an ill-fated illegal right turn, as "Many Saints" depicts it — rumors swirled that police officers had killed yet another African American.

The Newark Rebellion was about to begin.

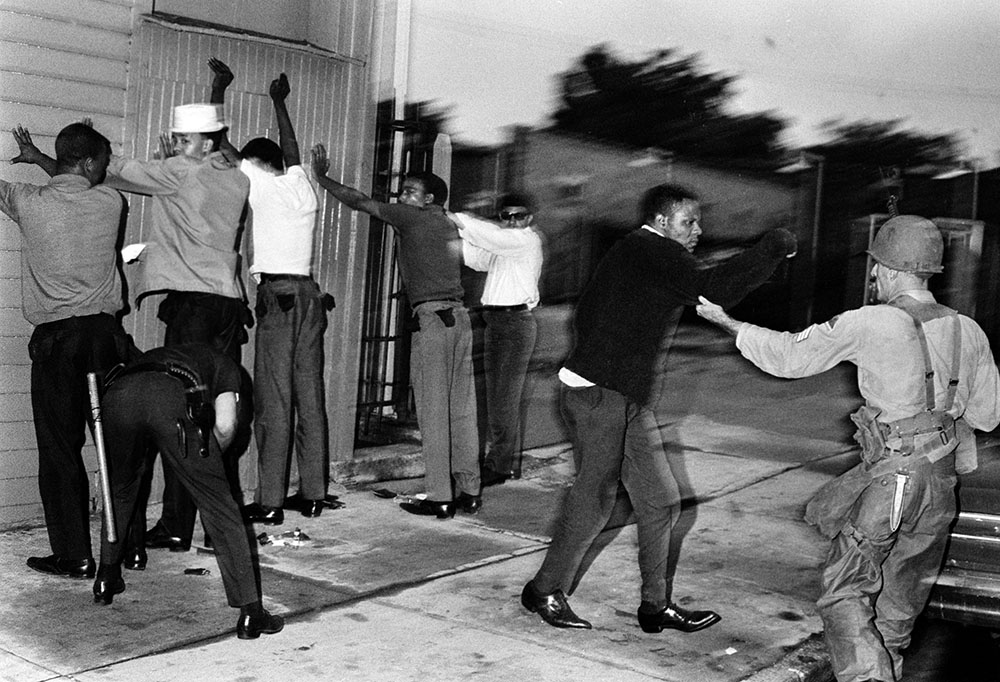

In this historical photo, a National Guardsman moves a Black man toward a wall as police search others in Newark, New Jersey, on July 15, 1967, during the Newark Rebellion. (AP Photo)

"For me and ['Many Saints' co-writer] Lawrence Konner, we were coming of age in the 1960s," Chase notes. "And so many of the issues of the 1960s never went away. And that's why we wrote [about the riots]. What we didn't know is that when [filming] shut down for COVID that the whole thing would come back again full force," Chase says, referring to the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020.

In other words, what already had plenty of resonance and relevance before the George Floyd murder, and the global uprisings that followed, has become even more timely now that "Many Saints" is finally hitting the big screen.

These days, St. Lucy's offers Mass in Spanish for new arrivals from Central America, who are now among the parishioners helping to raise funds to repair the fire-damaged rectory. The much-anticipated St. Gerard Feast in October will also help out with that. Novenas and venerations of the St. Gerard relic will also be held Oct. 5-13.

To see other aspects of Italian Catholic life that "The Many Saints of Newark" does not touch upon, people can schedule a visit to the captivating Museum of the Old First Ward, curated by Cascella.

Or, for an even more intimate glimpse into First Ward history, Father Paul celebrates Mass every Sunday at 8 a.m. — in Italian.