A woman and two girls look at their destroyed house during World War II in Russia in the Soviet Union, Sept. 1, 1943. (Wikimedia Commons/RIA Novosti archive, image #982/S. Alperin/CC-BY-SA 3.0)

I'm sometimes asked what I've learned from my years covering humanitarian issues. One is that men initiate wars, and women and children are left to deal with the consequences of the wars that men create. I have seen that again and again, be it in South Sudan, Colombia or Afghanistan.

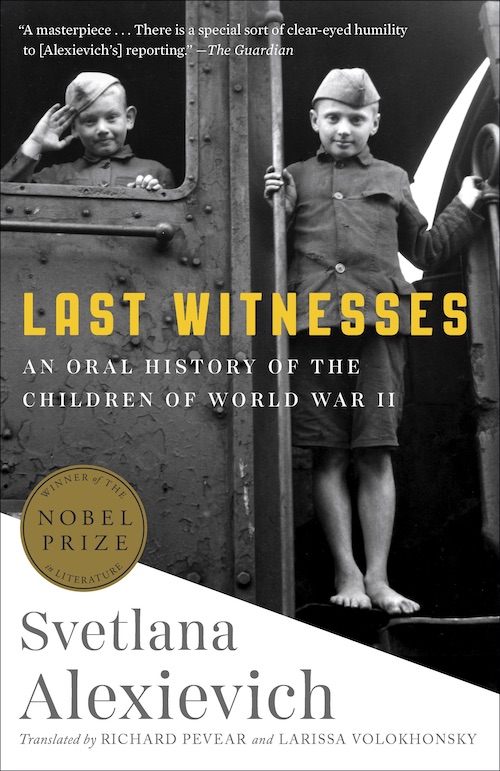

In that spirit, Last Witnesses: An Oral History of the Children of World War II by Nobel Prize winner Svetlana Alexievich comes at the right time: a reminder of the very real and lived consequences of state-driven violence perpetuated by men.

To be clear: The subtitle of Alexievich's book is a bit of a misnomer. This is not an all-encompassing oral history of World War II but one focused on the children who lived in the Soviet Union during the war and who as adults looked back on their experiences.

Svetlana Alexievich in 2013 (Wikimedia Commons/Elke Wetzig)

The focus on the Soviet Union is more than sufficient as a subject, of course, and it fits in perfectly with Alexievich's larger project of focusing on Russian and Soviet history — "polyphonic writings, a monument to suffering and courage in our time," as the Nobel committee in 2015 so aptly put it.

Last Witnesses was originally published in Russian in 1985 and only recently in English. Its U.S. appearance in paperback this past summer, after a hardback release last year, was perhaps intended to coincide with this year's commemorations of the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II in 1945.

Those commemorations have been muted, given the global health pandemic. But that development actually works to the book's advantage, drawing attention away from official history and sites of battle to the lesser-known locales of violence where civilians were vulnerable to horrific acts.

There are too many of those to recount, but they linger in the mind long after finishing the book.

"I saw a German train go off the rails and burn up during the night, and in the morning they laid all those who worked for the railroad on the tracks and drove a locomotive over them," one survivor recalled.

After a round of German-led executions, one child at the time remembered that a German soldier drove over the dead and smashed their heads. "I had never heard the sound of cracking human bones. ... I remember that they cracked like ripe pumpkins, when my father split them with an ax and I scraped out the seeds," the survivor recalled.

The specificity of such horrors is searing — though they are set against the memories of children recalling acts of courage and love, particularly by parents trying to protect their children.

Alexievich has artfully framed the recollections and affirmed the place of memory in her interviewees' lives: The first words, spoken by Zhenya Belkevich, encompass a whole world: "I remember it. I was very little, but I remember everything." Nearly 300 pages later, as a coda, another survivor, Valya Brinskaya says: "We are the last witnesses. Our time is ending. We must speak. ... Our words will be the last."

If they are the last, they also capture the innocence that war abruptly ended. Brinskaya describes the suddenness of war's appearance: a burning sky. "Papa, is that a thunderstorm?" she asked her father.

"Stay away from the window," he replied. "It's war."

In that context, children grow up quickly. "Were we really children?" one survivor mused. "By the age of ten or eleven, we were men and women."

Advertisement

One survivor whose family became Soviet partisans recalled using frozen German corpses as sleds even after the war ended. "They [the bodies] could be found outside town long after the war. … You could kick the dead man with your foot. We jumped on them. We went on hating them."

A reader suspects the war's lasting trauma was perhaps more pronounced than the survivors admit. But a few are forthright about the depth of those experiences. Survivor Vera Zhadan recalled that she and those in her village were forced at gunpoint by German soldiers to bury a group of partisans and were told that whoever cried would be shot.

"They forced us to smile," she said. "I bend down, he comes up to me and looks me in the face: am I smiling or crying? They stood there ... All young men, good looking ... smiling."

For Zhadan that resulted in a lifelong trauma of shunning young men. She told Alexievich that she never married or "knew love" as a result. "I was afraid: what if I give birth to a boy."

The interviews are presented "as is," without context of how the interviews were gathered, and it might have been helpful to know a bit about that context. All that is said is that the interviews were conducted from 1978 to 2004 — presumably Alexievich added to what was in the Russian-language edition that was published in the mid-1980s.

The reader is left to imagine the silences and things left unsaid. There are only hints of the war's widespread sexual violence against women. Thankfully, there is a growing body of literature on that tragic aspect of the war. (There is also an expanding field of academic study about women, gender and war, and a good place to begin exploring that important topic is a 2013 anthology titled Women & Wars, edited by Carol Cohn.)

The testimonies in Alexievich's book are sometimes difficult for a reader to take in for long sweeps of reading. Yet even so, Last Witnesses has a power that is touching, stirring and often deeply sad.

Tamara Parkhimovich, a secretary-typist, said her happiness is always clouded by memories of war. "I can never be completely happy. Totally happy. It somehow doesn't come out. I'm afraid of happiness. It always seems that it's just about to end. This 'just about' always lives in me. That childhood fear."

[Chris Herlinger is GSR international correspondent. His email address is cherlinger@ncronline.org.]

Editor's note: Love books? Sign up for NCR's Book Club list and we'll email you new book reviews every week.