Trinity Catholic High School in Spanish Lake township, north of St. Louis, pictured in May 2020 (Wikimedia Commons/DiamondRemley39)

On the evening of Feb. 25, Kimora Williams, 17, and Elijah Brooks, 16, two juniors at Trinity Catholic High School north of St. Louis, both saw emails flash onto their computer screens.

They were from the St. Louis Archdiocese. Trinity Catholic would close at the end of the academic year. The two were stunned.

"I was angry. I was confused. I was overwhelmed," Williams told NCR.

A letter attached to the email said that enrollment at the school, located in a predominantly African American area just a 15-minute drive from Ferguson, Missouri, had slipped too low and the building was too old to maintain.

Williams and Brooks came to Trinity for the reasons many other Black students do: The academics were better than at the nearby public schools, but Trinity also felt like a family.

Now, they feel betrayed.

"I do feel that the archdiocese has abandoned the community, especially a community that is predominantly Black," Williams said. "I feel that it is racially motivated for them to close us, because I feel like if it was in a predominantly white neighborhood that would never be a choice."

Coincidentally, the announcement came just hours after the pair, who head the school's diversity club, had put on the school's Black History Month assembly.

"I was starting to feel like I was actually making a change within my community and in my school," Brooks told NCR. "I feel like it's all gone to waste."

Kimora Williams, left, and Elijah Brooks stand outside Trinity Catholic High School in Spanish Lake township, Missouri. The St. Louis Archdiocese will close the school at the end of the 2020-21 school year. (Courtesy of Beth Lappe)

Trinity is just one of the hundreds of Catholic schools to be shuttered since the pandemic began, but the school, which teachers say is more than 80% African American, highlights another trend: Schools serving Black students are more likely to close.

Statistics compiled by the National Catholic Educational Association show that in 2020 Black students represented just 7% of Catholic school students nationally, but they made up 18% of students in schools that closed.

Of the 147 closed schools for which the NCEA has data, the association said 34 were majority-minority.

Many African American students and parents believe Catholic schools provide better opportunities for their children at an affordable price. However, the closures have them asking if the church is withdrawing from Black communities and retreating from the values it claims to espouse.

It has also left many wondering if the same decisions would have been made if their students were white.

But archdiocesan officials insist the closings are not racially motivated.

"It's a very small group that feel this was racially motivated," Peter Frangie, a spokesman for the archdiocese, said. "That is absolutely not the case. The archdiocese has been very present in our African American communities and supporting them in the best way possible."

Advertisement

The story of Trinity Catholic is closely linked to the broader shifts taking place in north St. Louis County.

Beth Lappe, a special education teacher and the school's union steward, told NCR that since the civil unrest that shook the neighborhoods around Trinity following Michael Brown's death in 2015, many white families have moved away.

In just a few years, Trinity's student body went from majority white to now being over 80% Black.

Students, teachers and parents at Trinity interviewed by NCR expressed frustration that the archdiocese would be closing the high school after already closing two predominantly Black elementary schools that fed into Trinity at the end of the last school year.

"I would say we broke a covenant with our students and our families," Lappe said. "I thought we had the political will to keep the school open."

Frangie told NCR that Trinity was not treated differently than any other school; the decision to close came down to numbers, not race.

According to an online local school tracker, Trinity's enrollment for the 2017-18 academic year was 326 students. Frangie said the enrollment number is currently 284 students.

The class of 2021 will graduate 77 students, but the current freshman class counts 44 students, and 37 students were signed up to matriculate next year, said the spokesman.

"These are not easy decisions," he said. "It wasn't feasible to keep Trinity open long term."

The spokesman added that in 2017, the archdiocese shuttered John F. Kennedy Catholic High School, an overwhelmingly white school, after its enrollment fell to 280 students.

Many Catholic schools that now serve Black students share a similar history.

As Catholic immigrants left the inner cities for the suburbs after World War II, Black students began to replace them in the Catholic schools they left behind, according to Nicole Stelle Garnett, a law professor at the University of Notre Dame, who has extensively researched urban Catholic schools.

Black parents were attracted by Catholic schools' academic rigor, and Catholic leaders saw it as their mission to educate students in need.

Garnett told NCR that years of research have shown that Black students in Catholic schools perform better academically and attend college at higher rates than their public-school peers. The benefits are the greatest for the economically poorest students.

However, those urban schools have struggled the most with enrollment in the past several decades NCEA data shows.

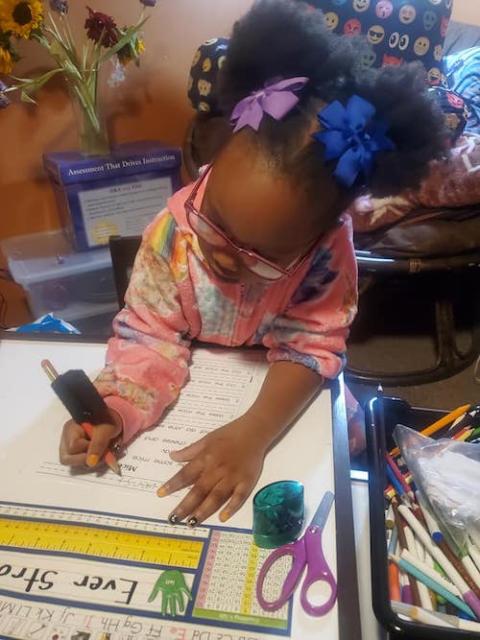

Ever Strong, Carolyn Strong's daughter in first grade at Christ Our Savior Catholic School, which the Chicago Archdiocese is closing, practices her penmanship. (Courtesy of Carolyn Strong)

Even the Trinity's most ardent supporters admit the school was in a precarious financial position.

The archdiocese had to subsidize Trinity more heavily than any other school in the system, and only nine families were paying full tuition, according to Lappe, the union steward.

Mary Pat Donoghue, the executive director of the Secretariat of Catholic Education at the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, said that schools serving Black students have not been able to find new students as easily as their whiter suburban counterparts, and that the disproportionate closures are not intentional.

"The church has been long committed to the education of Black students," she told NCR. "It's a heartbreaking situation, and we certainly hear and understand that sense of abandonment."

Carolyn Strong, a nationally recognized expert on Black girls' experience in the classroom, argues that the church should back up its commitment to Black communities with funding.

"I understand that things come down to dollars and cents," she told NCR. "But at the same time, if you are a religious organization with an arm that is solely dedicated to outreach and ministry and all of these things, on what planet is it a good idea to close schools within a community that is being hit hardest by this virus?"

Strong is currently trying to find a new elementary school for her own daughter after the Chicago Archdiocese announced majority-Black Christ Our Savior Catholic School in South Holland, Illinois, will close at the end of this year.

In a statement to NCR, Jim Rigg, the superintendent of Chicago Catholic schools, said that the archdiocese had poured more than $1 million into Christ Our Savior over the last four years to support a school with only 129 students, an arrangement that was no longer tenable.

Research by Garnett, the Notre Dame professor, suggests that Catholic school closures in inner cities do not just hurt the families they serve but can hasten an entire neighborhood's decline.

Garnett and a colleague studied neighborhoods in Chicago and Philadelphia and found that crime fell more slowly, and other indicators of social disorder rose, in areas where Catholic schools had closed than citywide averages.

"In some neighborhoods the school was the last remaining really vibrant social institution," she said. "To have a school run by a private institution, the Catholic Church, that is not just surviving but thriving sends the signal that all isn't lost here."

Aaron Brady, Latoya Brady's son, is part of the last senior class at Trinity Catholic High School in Spanish Lake township, Missouri, which will close at the end of the year. (Courtesy of Latoya Brady)

Back in north St. Louis County, Latoya Brady, 37, is a proud Black Catholic. She told NCR that even after losing her job, she found the money to send her son to Catholic elementary school.

This summer, he will be part of the last graduating class of Trinity Catholic, the last Catholic high school in north St. Louis County.

Brady feels her church is abandoning her community.

But what makes Brady the most upset is that the archdiocese is now urging parents to send their children to Catholic schools in other communities, often majority white schools.

"They're always taking away from our community and expecting us to go and pay our money to other communities to build them up and make them better while ours is suffering," she said.

[Alexander Thompson is a freelance journalist covering K-12 Catholic education from Boston.]