A worshipper prays a rosary at the metropolitan cathedral in Curitiba, Brazil, in this 2014 file photo. (CNS/Amr Abdallah Dalsh, Reuters)

Pope Francis' response to a letter about racism in the Catholic Church, sent to him by a group of Brazilian priests and bishops, has been received with hope by Black Catholic activists across the South American country.

The letter had been sent to the pope on June 19 by the group Padres e Bispos da Caminhada (roughly, Walking Priests and Bishops), which includes many progressive Brazilian clergy.

It was signed by 83 priests and five bishops and addressed themes such as alleged harassment of Black seminarians and the barriers for Black priests who wish to become bishops.

The group's missive began with the citation of a few verses from a long poem written by the Brazilian abolitionist author Castro Alves, called "The Slave Ship." Published in 1870, it describes the horrors of the transatlantic crossing of captured Africans who were taken to the Americas.

The priests introduced themselves as "descendants of Mother Africa" and mentioned the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, connecting it to their own experiences.

"Getting straight to the point, we, black priests, in order to answer to the call of Jesus Christ, our Lord, as laborers of His Harvest, feel during our formation our educators' knees pressing our necks," the letter said. "We know what the outcry 'I can't breathe' means."

The priests said they had been "mocked" and "undervalued" during their formative years, always remaining "silent" and "choked up," fearing they might not be approved to receive holy orders.

Advertisement

The group also questioned the process for choosing bishops in the country, claiming that the Vatican embassy, known formally as an apostolic nunciature, "operates without duly consulting the local churches, not even the bishop that will be replaced due to his age."

"In a country of black [populational] majority, may we have more black bishops," the priests asked.

"Why can't a black priest can't be a bishop? Is the choice connected to white supremacy?" the clergymen continued, also saying they are tired of "vain and careerist diplomats."

The pope opened his response, which was written by hand and dated Sept. 9, with praise for Alves' verses, which was widely seen in Brazil as a sign of his commitment to the struggle against racism.

Francis said he will take into consideration what the Brazilian priests told him and said he feels "close" to them.

"I will talk about it with Cardinal Marc Ouellet, Prefect of the Congregation for Bishops," said the pontiff. "I understand what you say about the Nunciature and the way of choosing the candidates to the Episcopate. Now a new nuncio is arriving and I will also talk to him."

The new nuncio, or Vatican ambassador, is Archbishop Giambattista Diquattro. Francis transferred him away from India at the end of August to replace Archbishop Giovanni D'Aniello, who has been moved to Russia.

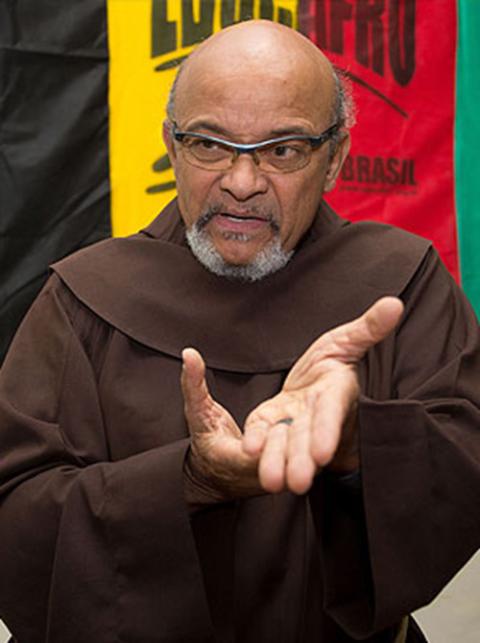

Fr. David Santos (Courtesy of Universidade Federal de Pelotas)

Francis' message has been celebrated by many Catholic Black activists, who consider it historic.

"He avoided the bureaucratic channels and answered to the black priests by hand," said Franciscan Fr. David Santos, a longtime activist of Black liberation in Brazil who leads the nongovernmental organization Educafro.

Fr. David Santos (Courtesy of Marcos Santos/USP Imagens)

Santos said one of the motivations of the group to write the letter to the pope was a public statement released by the Black priest Fr. Geraldo Natalino in June. In a social media outburst, Natalino described the Brazilian church as "structurally racist."

Natalino said that throughout his education as a priest, he only had white professors. He also said that he spent 10 years at a parish but had to ask the local bishop to be confirmed as the new vicar. More recently, he claimed another bishop had obstructed his way to become a professor at a Catholic university, despite his qualifications (he holds a doctorate).

"Natalino and I had the idea to report the several elements of racism in our daily reality to the National Conference of Bishops of Brazil and to the pope," said Santos. "We're happy that the Walking Priests and Bishops already opened the way with this document."

Indeed, Natalino's complaints aren't uncommon at all among Black priests and nuns.

"In my experience, I can say that racism is the rule for most Blacks in the church," said Fr. Ivanil Pereira da Silva, one of the letter's signatories. "I've been through it. It happens, but we usually try to ignore it and move on."

Nevertheless, the denunciation of acts of racism perpetrated inside the church is not usual. "The love that we have for the institution leads us to deal with it internally," da Silva said.

Sr. Telma Barbosa (Provided photo)

Sr. Telma Barbosa, a Black artist and activist, said racism has been traditionally hushed up in the church due to the powerlessness experiences by victims in the church's hierarchical structure.

"Commonly the victim doesn't have courage to tell other people about the problem," Barbosa, a member of the Franciscan Sisters of Ingolstadt, told NCR. "At times, we want to avoid the idea that we're 'agitators.' We usually have to forgive the person and keep silent."

However, Barbosa said she has always adopted an outspoken attitude when she has experienced discrimination.

She cited many cases in her ecclesiastical life: from a colleague who used a derogatory word in regard to her hair, to the case of an outside visitor who felt insulted when she, a Black woman, asked him to stop damaging the decorative plants of the sisters' house.

"He insulted me and threatened me. After that, he and a friend physically attacked me on the street," said Barbosa. A fighter of karate and capoeira (an Afro Brazilian cultural manifestation that combines dance and martial arts), Barbosa reacted and hit one of the attackers with her foot.

Joana Raphael (Provided photo)

Joana Raphael, a Black woman living in Rio de Janeiro, said she was a sister for seven years in the 1980s. Her childhood dream was to work as a communicator in a religious congregation and that was what she was finally doing in 1987, when she was suddenly expelled.

"At that point, I was deeply involved with Black activism and my superiors were always censuring me about it," she told NCR.

Raphael had already published two books involving Afro Brazilian themes, was a well-known organizer of Black social movements and frequently gave interviews to the press.

"My superior once told me: 'You can come down as fast as you went up,' " said Raphael, commenting: "A successful Black person is annoying."

After leaving the congregation, Raphael rebuilt her life and got married. A few years later, she left the Catholic Church and became a Baptist missionary. "I somehow wanted to answer that call," she said.

Fr. Lázaro Lourenço, who also signed the letter to the pope and leads the Instituto Mariama, the national association of Black bishops, priests and deacons, said racism in the Brazilian church is a direct fruit of the country's history of slavery, which has touched every sphere of society.

Fr. Lázaro Lourenço (Provided photo)

"Racism determines every social relation, including in the Catholic Church," said Lourenço. "But exclusion is not always so explicit."

In many parishes, Lourenço said, there's a "certain look and a certain mentality of disrespect in regard to Black priests like us."

"One of the results of such a situation is that there's a disproportionally low number of Black bishops in the country," he added.

But this is changing, said Feira de Santana Archbishop Zanoni Demettino Castro, who is also in charge of the Afro-Brazilian Pastoral Commission in Brazil.

"We now have about 40 black bishops in the country and they lead several episcopal commissions with a high consciousness of their ancestry," he told NCR. There are about 480 bishops in Brazil. More than 56% of Brazil's population of some 210 million identify as Afro descendant.

One of the Afro-Brazilian Pastoral Commission's main challenges is to promote the inclusion of Black culture as an integral aspect of evangelization, considering the gigantic presence of African elements in Brazil's social dynamics.

"It's not something separate from the church," Castro argued. "We have to be based on our concrete reality."

Archbishop Zanoni Demettino Castro (Courtesy of the Brazilian bishops' conference)

The Walking Bishops and Priests' letter was also signed by dozens of white clergymen, some of them European-born missionaries in Brazil. Such an attitude of empathy should be a model for society as a whole, said da Silva.

"First of all, they were humble enough to acknowledge that they're racists too," said the priest. "That's a fundamental step: to understand the other's pain and show solidarity."

"I'm very hopeful about change," said da Silva. "The pope's attitude of answering by hand was a true landmark."

[Eduardo Campos Lima holds a degree in journalism and a doctorate in literature from the University of São Paulo, Brazil. Between 2016 and 2017, he was a Fulbright visiting research student at Columbia University. His work appears in Reuters and the Brazilian newspaper Folha de S. Paulo.]