Narivaldo Dos Santos paddles a boat on the Ituqui River near his home in the Quilombo Bom Jardim, outside Santarem, Brazil, March 10, 2019. (CNS/Paul Jeffrey)

In reading your exhortation and the responses to your words, my thoughts returned to one of our own U.S. authors who bears within himself the blood and stories of generations of indigenous, diasporic, Latin@́ and Asian peoples. Alfredo Véa Jr. is a Mexican-Yaqui-Filipino-American who wrote almost a quarter century ago:

You must seek out remembrance, for ours is a land of amnesiacs who pretend that there is no past; that America is a multi-cultural land when, in truth, it is an anticultural place that has ever been blessed with persistent and enduring cultures that have survived never-ending efforts to drag them out of sight; push them out of mind; to imprison them in the past (The Silver Cloud Café, 198).

Forgive me for Latinosplaining you, but we are in an age that believes it only takes an hour to read your text carefully and reply, preferably, in a series of 280-character tweets. You dared to respond to los gritos of our sisters y nuestros hermanos whose cries literally arise from la tierra, in a lyrical manner that is both message and method, through a frame of dreams — a medium of communication understood among many indigenous people. You signaled to us how dear this place and people are to you through the title the exhortation bears across translations — in Spanish, not Latin, Querida Amazonia. You have told us before that español "es el idioma de mi corazón" and when you speak from the heart you turn to your mother tongue.

What happens when we interact with the totality of your exhortation as you do, as a reflection on Amazonia as a locus theologicus, a space where God reveals the divine self and summons the children of God (#57)? How might we understand your call if we engage each dream from a hermeneutic of intimate exchange? Your use of "querida" establishes a context of intimacy, a term of endearment, a salutation to loved ones, an adjective indicating belovedness. It offers a lens for interpretation as well as for the invitation to engage.

The interweaving of dreams is familiar to you, a favored way of sharing across generations. In the synod's final document dreams appear but once — in reference to the young (#30, #32). In your 2019 exhortation following the synod on youth, you tied the dreams of elders to the visions of the young, a necessary exercise in expanding horizons (Christus Vivit, #192-193). Rooted in what you called the "very first dream of all," the "creative dream of God" ever present in our lives, you encouraged us to hold on to the memory of that blessing that extends from generation to generation (#194). You urged that we let our elders tell their stories no matter how fanciful because "they are the dreams of old people — yet are often full of rich experiences, of eloquent symbols, of hidden messages. These stories take time to tell, and we should be prepared to listen patiently and let them sink in, even though they are much longer than what we are used to in social media" (#195).

Mi querido abuelo en la fé, I suspect these, your earlier words, provide a helpful key to situate the four interlocking sueños in your most recent exhortation, informed in part by the dreams of the elders and ancestors of Amazonia. Some of our poets too had dreams and cautioned us mightily of what would occur should we let them fester and then explode. Langston Hughes thought a lot about dreams and observed "A certain amount of impotence in a dream deferred" ("Same in Blues").

Advertisement

Your first sueño is a social dream predicated upon making a preferential option for those who are made poor, marginalized and excluded (#26). You underscore that such an option is not one of "doing for" or "deciding for" others relegated to the margins of societies; rather, it a radical affirmation of the agency of those made invisible and deemed incapable of speaking for themselves. You caution that those among us who feel compelled to "do for" must understand dialogue as a table to which we are called to participate "as 'guests' and to seek out with great respect paths of encounter that can enrich the Amazon" as determined by what constitutes "good living" by Amazonians themselves and "for those who will come after them" (#26). Proposals from the privileged must secure permission, authority rests with the locals, peoples who are indigenous, Afrodescendants, mixed, migrants, poor — and whose ways, rooted in ancient wisdom passed down, or in need of retrieval, may provide paths forward for the region and for the care of our common home (#27). The gifts of indigenous peoples include their values and wisdom regarding right relationship with the environment and you affirm that this is their contribution to the common good — something we can all stand to learn.

You connect the destruction of the environment to the destruction of peoples and cultures, a way of emphasizing that the relationship with creation is a social one, too! This leads to your second dream, a cultural sueño. At a time when too many pundits in the U.S. disparage talk of identity as polarizing, reducing our careful connections between roots and oppressions to shallow charges of identity politics, it is refreshing to see you declare that "identity and dialogue are not enemies" (#37). Furthermore, you insist that our roots, in all of their complexity and differences, are starting points not obstructions to shared hopes. One of our U.S.-México bilingual, binational Chicano poets, Francisco Alarcón, captures this engrained relationship "mis raíces las cargo siempre conmigo enrolladas me sirven de almohada / I carry my roots with me all the time rolled up I use them as my pillow" (Laughing Tomatoes/Jitomates Risueños, 5).

Edimilson Ferreira Nascimento, 37, leader of the God and Life Association, an organization of small farmers, prays over the food being prepared in his rural home near Anapu, in Brazil's northern Para State. Beside him is Sr. Jane Dwyer, a Sister of Notre Dame de Namur from the United States. (CNS/Paul Jeffrey)

Shanenawa people dance Sept. 1, 2019, during a festival to celebrate nature and ask for an end to the burning of the Amazon, in the indigenous village of Morada Nova near Feijo, Brazil. (CNS/Reuters/Ueslei Marcelino)

At the same time, talk of raíces inevitably necessitates contending with the ongoing legacies of colonization and violence that seek erasure and, over the centuries, have driven original peoples deeper into the forests and now out of their refuge and into the streets of cities — further damaging memory and impeding its transmission. Such a care for roots cannot escape the impact of slavery and forced migrations, a ravaging of human dignity based on identity and raíces.

Throughout this second dream you make what we Latin@́ theologians call a preferential option for culture. Such an option intentionally embraces cultural dimensions of our lives and faiths, a nuanced contextualization that sees en lo popular possibilities of encounter with the divine, expressions of solidarity, epistemologies of struggle. These explosions of creativity articulate — through word, art, music, craft, dance, story, play — the hopes, dreams, anxieties, suffering, dysfunctions, joys, relationships inherent in our human navigations of our intersecting worlds. You find, in Amazonia, identities forged in multiple and even disparate cultures, because, as you acknowledge, "Human groupings, their lifestyles and their worldviews, are as varied as the land itself, since they have had to adapt themselves to geography and its possibilities" (#32). The topography and the people, in the richness of their diversity, reflect their creation in the divine diversity, because in that "God manifests himself and reflects something of his inexhaustible beauty" (#32). In this regional richness, creative inspiration is dawn from "its water, its forests, its seething life, as well as its cultural diversity and its ecological and social challenges" (#35).

It is these distinctive natural features that drive your third sueño, an ecological dream. Again you turn to "poets, contemplatives and prophets" to convey the urgency of the cries arising from the intrinsically connected and endangered people and ecosystem. Your option for poetry here is particularly intriguing because this dream would appear, at first, to be better suited for the sobering and technical verses of the scientists. Hints of Brazilian liberationist Rubem Alves peek through, a caution to theologians as well "Theology wants to be science, a discourse without interstices… ⁄ It wants to have birds in cages… ⁄ Theopoetics instead, empty cages…" (The Poet, the Warrior, the Prophet, 99).

Your call to the conversion of hearts requires language that opens the imagination. This dream, more so than the others, leads us back to "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home" where the sciences informed your reflections. There is no need for redundancy because this exhortation should be understood, read and interpreted within the greater context of your body of teachings. Your interlocutors, whose good will is presumed, must be invited to "feel with" Amazonia because our collective survival is at stake. Solidarity in this case requires a dis-comforting, a sacrifice of consumerism and waste, a relinquishment of profit in a move that is both altruistic and self-preservationist.

Yet, as I look within my own country of origin, our political leaders push back years of environmental protections, detach our nation from global obligations, utilize a human abetted climate catastrophe to exploit a colonized island and its people whose citizenship is treated as second class at best. I wonder, what does it take to stir conversion of the colonizers, the complicit and the indifferent? How many scientists and poets and prophets and popes? The nonbinary and bilingual Puerto Rican author Raquel Salas Rivera pushes those edges with their poetry in the aftermath of Hurricane María:

the weeks after the hurricane, the months, what i dreaded most was this newfound awareness that we existed. i knew that no matter how loud i screamed, the knowledge i had acquired through love and death meant nothing to these ex-colonized colonizers. they would only hear echoes of their own good deeds, like so many missionaries kneeling before a familial god (while they sleep (under the bed is another country) ).

Your final sueño, an ecclesial dream, has garnered a disproportionate amount of attention, in part because others beyond the region have pinned some of their dreams too on what would arise from re-envisioning ministries. Your four dreams are certainly Amazonia specific because they are in conversation with the fullness of the synod and its final document. You affirm the local experiential wisdom, knowledge and authority of those who prepared it and are clear that your presentation is official and you are not quoting it because you "encourage everyone to read it in full" (#3). Consistent with your apostolic constitution Episcopalis Communio on bishops' synods, it "participates in the ordinary Magisterium of the Successor of Peter" (Article 18, #1). Now as for the reception and implementation of the final document — that responsibility rests in the hands of the bishops.

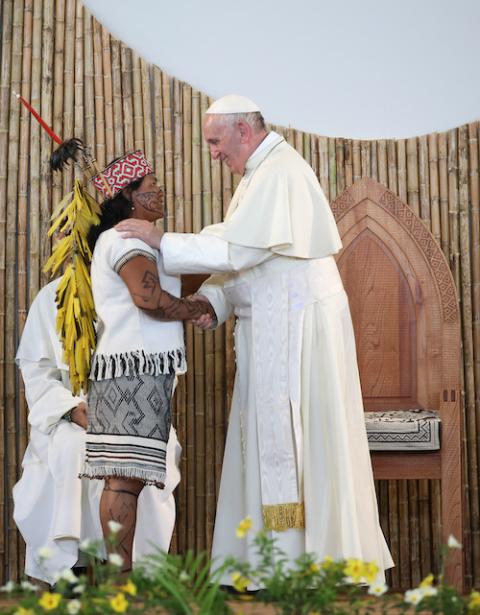

Pope Francis is greeted by a member of an indigenous group from the Amazon region during a meeting at the Coliseo Regional Madre de Dios in Puerto Maldonado, Peru, Jan. 19, 2018. (CNS/Reuters/Alessandro Bianchi)

This sueño is more provocative than it seems. With respect to women deacons and married priests, you leave the window open, though your concern for avoiding new patterns of clericalism should be heeded. In part, I suggest this power malformation feeds off of a privileging of personal or individual calls to ordained vocations. The focus in Amazonia shifts the source of ministerial calls to the needs of particular communities, communities who have raised up leaders 60% of whom are women. You do not qualify your urging for prayers for priestly vocations with the words celibate or male, an interesting omission, though you still struggle with the temptation to frame ministry within in terms that essentialize gender. You have gifted us with rich new metaphors for the doing of ministry and theology, images like "field hospital," "the smell of the sheep," "the smell of the street." Reliance on dated metaphors like the church as bride of Christ takes on a literalism that can prove counterproductive, limiting our openness to the Spirit who will blow as she will.

You sense new directions in Amazonia that present opportunities for "the Church to be open to the Spirit's boldness, to trust in, and concretely to permit, the growth of a specific ecclesial culture that is distinctively lay" (#94). On the ground you see base communities, again often lay lead, as "experiences of synodality" (#96). The synod's final document calls for a diaconate formation process that includes the participation of the candidate's spouse and children (#105). How does such an expectation expand notions of collaborative ministry by proposing what is in effect a function of diakonia en conjunto?

When it comes to ministry, you invite the rest of our local churches to do the hard work accomplished by all who spoke out, listened, prepared and participated in the synod process arising from the particularity of Amazonia. Develop an interactive process, identify the pastoral needs of our places, and, with our bishops, recommend courses of action that do not tax the ministries of communities whose own needs eclipse our own. Tucked into a footnote, you call out a practice illustrating that even in Eucharist the privileged are fed at the expense of those who struggle to set their own tables: "It is noteworthy that, in some countries of the Amazon Basin, more missionaries go to Europe or the United States than remain to assist their own Vicariates in the Amazon region" (Note #132).

Altar servers process following Mass April 6, 2019, in St. Ignatius, Guyana. (CNS/Paul Jeffrey)

There was a time once, in my own youth, when some of our U.S. bishops wrote passionately and lyrically about the cries and connections of their people to la tierra. In 1975, bishops who called the Appalachian region home, moved by the same Spirit you invoke, sang of "the dream of the mountains' struggle, the dream of simplicity and of justice." Your words brought back from memory the pastoral poetry that had touched the heart and imagination of this city kid, verse that called us to care about places that others called home yet impacted us all, a precursor to your understanding of an integral ecology. Almost half a century ago our bishops' words, too, leapt off the page inviting us to dream a better world:

hopefully the Church

might once again

be known as

— a center of the Spirit,

— a place where poetry dares to speak,

— where the song reigns unchallenged,

— where art flourishes,

— where nature is welcome,

— where little people and little needs come first,

— where justice speaks loudly,

— where in a wilderness of idolatrous destruction the great voice of God still cries out for Life. (This Land Is Home to Me)

In solidarity with the peoples of Amazonia, motivated by the Spirit's wild ways, may we have the power to remember, the humility to learn and the courage to act.

[Carmen M. Nanko-Fernández is professor of Hispanic theology and ministry, and director of the Hispanic Theology and Ministry Program at Catholic Theological Union (CTU) in Chicago. The author of Theologizing en Espanglish (Orbis), she is currently completing ¿El Santo?: Baseball and the Canonization of Roberto Clemente (Mercer University Press).]

Editor's note: We can email you every time a new Theology en la Plaza column is posted to NCRonline.org. Go here to sign up.