(Unsplash/Umit Bulut)

Five years ago, Toni Morrison, the late Nobel laureate and prodigious novelist, wrote a short article for The Nation magazine on the occasion of the publication's 150th anniversary. The piece, titled "No Place for Self-Pity, No Room for Fear," centered on the recalling of her emotional state in the wake of President George W. Bush's reelection in 2004. She remembers a phone conversation around the Christmas holiday that year with an artist friend who asked how she was doing.

Her response was frank: "Not well. Not only am I depressed, I can't seem to work, to write; it's as though I am paralyzed, unable to write anything more in the novel I've begun. I've never felt this way before, but the election ..."

At which point her friend interrupted her.

As Morrison recounts, he said: "No! No, no, no! This is precisely the time when artists go to work — not when everything is fine, but in times of dread. That's our job!"

I have been reflecting on this exchange between two artists, two friends, two people whose conversation could have taken place this week or next week or during any other time of dread and fear. Unlike the shortsighted and often insensitive memes that circulated online early in the COVID-19 pandemic that pointed out the potential productivity benefits of a forced sequestering of the masses, the exchange between Morrison and her friend does not make a capitalist claim about the value of time and the importance of production.

Instead, the exchange highlights the fundamental importance of creativity, especially during times of immense suffering, chaos, loss, confusion, illness and even death. The message is one of returning to the core of who each of us is and what is most important for each of us to do at this time: Artists must create, writers must write, physicians must heal and believers must pray. This is imperative not because there is a monetary return on the investment of one's time in isolation, but because these activities are more than busy work or commodity production — they are reflections of what is most important to each of us and, most importantly, an expression of who we really are.

Like Morrison's struggle to write in December 2004, I have often found myself struggling these last few weeks to do something that I am expected to do almost naturally by virtue of my life and profession: that is, pray.

One doesn't have to be a member of a religious order or an ordained minister to feel the call to prayer and simultaneously struggle to do just that. As much as a visual artist paints or a novelist writes, a Christian believer's prayer life ought to flow from the core of their being, for it is a response to their creator's invitation to relationship. And yet, like artists and writers who hit a "dry spell" or "writer's block," believers can struggle to find the inspiration or motivation to turn to God in prayer. Or, as is also quite common, when one does muster the strength to pray, it can feel as if God is not there, not listening, not real.

There are moments in my lifetime that have challenged my ability to do what a believer is meant at their core to do. There have been times of dread and fear, anger and sadness, frustration and disappointment at the world and the God who supposedly created it out of love.

I think of being a college student on Sept. 11, 2001. I think of being a young Catholic discerning a vocation to religious life in the midst of the important and devastating revelations of clergy sexual abuse and its cover-up. I think of being a citizen of the world in an age of global climate change and escalating environmental catastrophes. I think of being a citizen of this country that elected a racist, misogynist, boorish, incompetent reality television star to the highest office in the land.

And, among other times, I think about the current moment, unprecedented in the lives of all those currently living on this planet, for which words and reason and prayer all seem to fall short.

I think about the suffering of many.

Advertisement

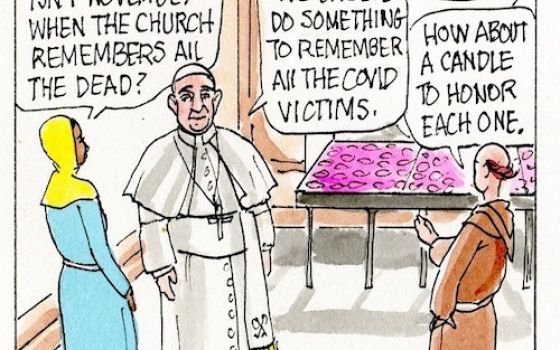

Millions have lost loved ones as hundreds of thousands have died. Hundreds of millions more are thrown into a state of financial precariousness that would have been unthinkable as recently as a few weeks ago. I think about the collective experience of shared anxiety that even infant children and domestic animals have picked up on and how the effects of this pandemic are in no way shared equally among the populations of this planet. The poor, the disenfranchised, the disabled, the elderly, the refugee and so many other groups of people are suffering and will suffer in a way the already privileged and powerful simply will not.

The reality of that much suffering weighs heavily on me, at times paralyzing me in moments of attempting prayer. And I have nothing to complain about, for I am one of those who fall on the privileged side of the scale. As a member of a religious order, I have a local community of support and the extremely rare opportunity to continue to celebrate the liturgical life of the church in our private chapel. As a graduate school professor, I have been able to work from home, migrating the remaining class lectures and assignments for my spring courses to a distance-learning format. I feel that my suffering is hardly suffering at all; my worrying is relative.

I wonder, "What can I do?" And I feel at a loss.

I ask, "Why is this happening?" And I hear silence in response.

I think, "Where is God?" And I begin to doubt.

The Trappist monk and spiritual writer Thomas Merton wrote in his 1956 book Thoughts in Solitude: "There is no such thing as a prayer in which 'nothing is done' or 'nothing happens,' although there may well be a prayer in which nothing is perceived or felt or thought."

This description speaks to me in the age of pandemic. When I struggle to perceive or feel or think during my attempted prayer, I am reminded that it is still worthwhile, still important.

Too often, the things that during normal times are dismissed as frivolous or silly or ephemeral or a luxury are in fact things that are most important: art, music, writing, prayer. These are the things that speak to what is truly meaningful and allow us as humans to make meaning in these times of meaningless suffering.

Morrison concludes her 2015 article with a reconsideration of her own response to times of dread and suffering, shifting her stance on the importance of what it is she is called to do but is struggling to do. She writes:

This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.

I know the world is bruised and bleeding, and though it is important not to ignore its pain, it is also critical to refuse to succumb to its malevolence. Like failure, chaos contains information that can lead to knowledge — even wisdom. Like art.

I am not an artist or a novelist, but I am a believer (or at least I try to be). And what a believer is meant to do at a time of dread and fear and suffering is to pray, or at least try to pray. In the trying, as Merton noted, something does happen, even if it's something I cannot perceive or feel or think.

At this point in our frightening present, prayer is not a silly pastime, a frivolous activity or a luxurious hobby; prayer is an essential thing to do. And for many of us, it may feel like the only thing we can do, even when we struggle to do it in the first place.

God is still alive, still drawing near to us, accompanying us in the midst of the suffering and fear — this I know, even if at times I struggle to believe. Like the father of the healed boy in the Gospel, I find myself proclaiming: Lord, "I believe; help my unbelief!" (Mark 9:24). And then I try to learn to pray again.

[Daniel P. Horan is a Franciscan friar and assistant professor of systematic theology and spirituality at Catholic Theological Union in Chicago. His most recent book is Catholicity and Emerging Personhood: A Contemporary Theological Anthropology. Follow him on Twitter: @DanHoranOFM.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out. Sign up to receive an email notice every time a new Faith Seeking Understanding column is published.