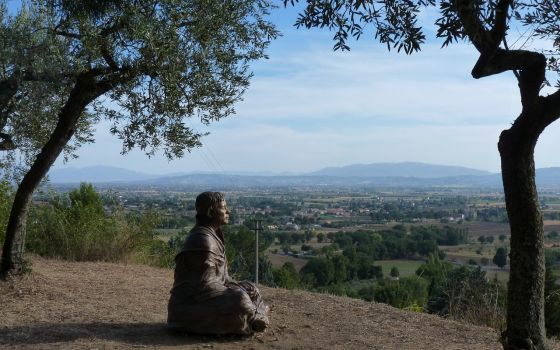

A sculpture of St. Francis of Assisi meditating on the grounds of St. Damiano, Assisi, Italy. (Pixabay/Sweetaholic)

There is a famous story about St. Francis of Assisi that takes place early in his experience of ongoing conversion to live a more committed Christian life. According to those friars who knew St. Francis during his lifetime and documented their stories of him in an early Franciscan text known as The Legend of the Three Companions, one day he was walking by the country church of San Damiano and felt led by the Holy Spirit to enter and pray before the crucifix hanging there. As he was praying, the crucifix "spoke to him in a tender and kind voice: 'Francis, don't you see that my house is being destroyed? Go, then, and rebuild it for me.' "

At first, St. Francis interpreted this revelation as an instruction for him to physically rebuild the dilapidated little church, which he eagerly did for some time: brick by brick. But over time he began to realize the broader implications of Christ's exhortation to him from the cross. It would seem that ultimately God was less concerned about the physical structures of this or that particular worship space and more interested in spiritual and moral renewal, a rebuilding of the church that is the Body of Christ. St. Francis' whole manner of living became focused on renewing the embodied, daily experience of Christian life by prioritizing the fundamentals of Gospel values in service to the poor, forgotten, voiceless and abandoned in his own time and context.

I thought of this important Franciscan narrative recently while considering the recent Vatican abuse summit called by Pope Francis, which closed on Feb. 24, and the wide ranging responses that have surfaced in response to what was said and done and what the summit failed to do.

Some people, particularly survivors of clergy abuse, have expressed frustration and disappointment with the lack of clear and concrete actions identified at the close of the summit. Others, like NCR's own Michael Sean Winters, have suggested that despite the absence of the kind of immediate action items some commentators have called for, the historic summit did make some notable progress in the effort to address the history of clergy sexual abuse and its cover up by bishops.

Advertisement

For example, the summit has raised the profile of this crisis to a global level in the church according to which bishops from around the world can no longer claim ignorance or exception. Directly naming related problems in ecclesiastical culture, such as clericalism and the priority of bella figura, and the resolve shown by those church leaders who spoke at the summit — e.g., Cardinals Blase Cupich of Chicago and Reinhard Marx of Munich and Freising, as well as Sr. Veronica Openibo, of the Society of Holy Child Jesus, who was clearly the M.V.P. of the gathering — suggests that this gathering of presidents of bishops' conferences will not be the last word on the subject.

Which brings me back to the San Damiano Cross. I was thinking of this Franciscan story in part because of the clear exhortation from Christ to "repair" or "rebuild" the church, which is precisely what I believe God asks of us today. But it also occurred to me that for as iconic as this scene in St. Francis' life has become, perhaps many Franciscans and others have been interpreting it incorrectly.

Typically, the story is understood as an instance when the saint from Assisi got it all wrong, at least at first. The general takeaway has been that St. Francis was too literal, concrete and shortsighted at first in his attempts to make sense of God's instruction to him. He focused on the physical decay of the structure before him rather than the bigger issue of spiritual and ecclesial reform. He only really got the true meaning later.

But what if the sequence of St. Francis' understanding and action is precisely the point? What if we were the ones who got the interpretation wrong and what St. Francis did was exactly what God wanted? What if you cannot begin to address the larger social, spiritual and theological issues until you fix those broken things that are right before you?

On the one hand, this seems like common sense. And yet, like the popular reading of St. Francis' response to Christ on the cross, there tends to be a different ecclesiastical approach to systemic challenges in the church. For example, I think of the January retreat for U.S. bishops held in Chicago, a time of prayer and reflection called for by Pope Francis himself. Obviously, prayer and reflection, penance and conversion ought to be at the heart of any bishop's spiritual life and pastoral ministry. However, I was struck by one report's summary of the retreat agenda, particularly its last line.

The structure of the retreat emphasized quiet reflection, including silent meal times, and daily Mass, time for personal and communal prayer before the Eucharist, vespers and an opportunity for confession. No ordinary business was conducted.

In light of the rereading of St. Francis' immediate response to Christ's mandate to rebuild the church, I have an even greater appreciation for the sense of disappointment and even anger shared by some of the faithful who might understandably wonder if the response to the crisis of clergy abuse and cover up has been out of order.

Pope Francis opened the Vatican summit last month by stating that the globally representative gathering of bishops was assembled to "listen to the cry of the little ones who ask for justice" and to consider "concrete and effective measures" in response. But four days later, the pope's concluding remarks at the end of the summit received understandably mixed responses given that he appeared at times to broaden his reflection from the specific history of abuse in the church and the urgent need to address it to focus as well on the reality of abuse in other contexts, such as in families or other parts of society. Though it's true that most child abuse happens within family contexts, that fact is irrelevant to the church's own handling of abuse by clergy and its covering up by bishops.

While after the close of the meeting Jesuit Fr. Federico Lombardi, the moderator of the Vatican summit, announced Pope Francis' intention to issue new laws and guidelines, including the publication of a handbook for bishops, there were no specifics issued or immediate instructions given for the bishops returning to their respective churches.

It seems to me that Pope Francis' namesake from Assisi offers church leaders a useful hermeneutic for interpreting Christ's exhortation to us today: repair the church, for as you see, it is falling apart! Priority must first be given the what is right before us, the women and men broken by abuse and silenced by trusted leaders that make up the church, which is the Body of Christ. They must be heard, their stories recognized and honored, and concrete actions must be taken. Rebuilding the church can only take place when each constitutive part is repaired and the structure is itself made whole. And the manner in which one does this rebuilding is important: as a penitent, with humility and in a spirit of prayer, just as St. Francis did eight centuries ago.

[Daniel P. Horan is a Franciscan friar and assistant professor of systematic theology and spirituality at Catholic Theological Union in Chicago. Follow him on Twitter: @DanHoranOFM]