A stained-glass window depicting St. Augustine and his mother, St. Monica, graces the wall at St. Augustine Church in Washington, D.C. (CNS/Elizabeth Bachmann)

We are nearing the finish in our weeklong retreat! Today, we shall examine the last two answers to the problem of Christ and culture that H. Richard Niebuhr identified in his book Christ and Culture: Christ and culture in paradox, and Christ as transformer of culture. Like those who synthesize Christ and culture, which we examined yesterday, both of these we shall examine today fall within the category of Christ above culture. The first, Christ and culture in paradox, has voiced "the strongest opposition" to the synthesists' efforts we looked at yesterday. What all three share is a "both-and" approach to the issue.

Niebuhr notes that the Christ-in-paradox-with-culture option is more a motif than a school and there are fewer "relatively clear-cut, consistent examples of this approach," which he labels dualism for reasons that will become obvious.

What is clear-cut is how they differ from the groups we have examined so far:

For them, the fundamental issue in life is not the one which radical Christians face as they draw the line between Christian community and pagan world. Neither is it the issue which cultural Christianity discerns as it sees man everywhere in conflict with nature and locates Christ on the side of the spiritual forces of culture. Yet, like both of these and unlike the synthesis in his more irenic and developing world, the dualist lives in conflict, and in the presence of one great issue. That conflict is between God and man, or better — since the dualist is an existential thinker — between God and us; the issue lies between the righteousness of God and the righteousness of self. ... The question about Christ and culture in this situation is not one which man puts to himself, but one that God asks him; it is not a question about Christians and pagans but about God and Man.

The Christian need not look far for those whose writings frequently display this dualistic motif: St. Paul, Luther and Kierkegaard are all dualists in this scheme, all existentialists in their way, never conflating God and culture and ending up in what appear to be some interesting places. However they end up, they start at the same place:

No matter what the dualist's psychological history may have been, his logical starting point in dealing with the cultural problem is the great act of reconciliation and forgiveness that has occurred in the divine-human battle — the act we call Jesus Christ. From this beginning the fact that there was and is a conflict, the facts of God's grace and human sin are understood. ... The knowledge of the grace of God was not given him, and he does not believe it is given to any, as a self-evident truth of reason — as certain cultural Christians, the Deists for example, believe. What these regard as sin to be forgiven and the grace that forgives are far removed from the depths and heights of wickedness and goodness revealed in the cross of Christ. The faith in grace and the correlate knowledge of sin that come through the cross are of another order from that easy acceptance of kindliness in the deity and of moral error in mankind of which those speak who have never faced up to the horror of a world in which men blaspheme and try to destroy the very image of Truth and Goodness, God himself [p. 150-151].

It should not surprise that these dualists are people who are compelling, dramatic figures. Romans 8, like the words of Martin Luther's hymn, "Ein feste burg," is not the stuff of gradualism, or synthesis, or any harmonious resolution of the problem. It could be said that the dualists do not seek to enlighten but to shock, and their approach is heavy on self-conviction as the means to wear down the human ego that it may receive God's grace.

"In a double sense the encounter with God in Christ has relativized for Paul all cultural institutions and distinctions, all the works of man," Niebuhr writes. "They were all included under sin; in all of them men were open to divine ingression of the grace of the Lord." The law of reason, like the revealed law of the Torah, both condemned humankind without exception, yet "in every position in culture and in every culture, in all the activities and stations of men in civilized life, they were also equally subject to [Christ's] redemptive work" (p. 160-161).

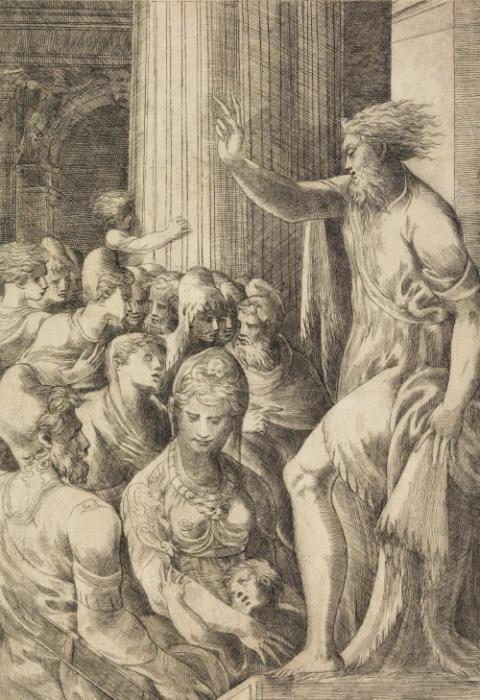

"St. Paul Preaching in Athens" (circa 1548-53) by Andrea Schiavone (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In Paul, we see clearly that "the whole edifice of culture is cracked and madly askew" (p. 155) but he believes, unlike the radical, "that the anti-Christian spirit could not be evaded by any measures of isolation from pagan culture, by any substitution of new laws for old ones, or by supplanting the pride of Hellenistic philosophy with the pride of Christian gnosis. ... Since the battle was not with flesh and blood but against spiritual principles in the minds and hearts of men, there was no hiding place for their attacks in a new, Christian culture" (p. 163).

Nonetheless, Paul did articulate a cultural Christian ethics, but ethics plays an entirely different role for him than it would for Thomas Aquinas. Connecticut is nicknamed the "land of steady habits," a Thomistic or Calvinistic accolade, but not something that would have occurred to Paul. For him, as for Luther, "the institutions of Christian society and the laws for that society, as well as the institutions of pagan culture in so far as they are to be recognized, seem more designed, in his view, to prevent sin from becoming as destructive as it might otherwise be, rather than to further the attainment of positive good."

The difference between the two approaches is thoroughgoing. The synthesist resolves the tensions he finds, but Paul holds on to the two related but markedly different ethics: "one is the ethics of regeneration and eternal life, the other is the ethics for the prevention of regeneration. ... there is no recognition here of two sorts of virtues, the moral and the theological. There is no virtue save the love that is in Christ, inextricably combined with faith and hope" (p. 166). There may be no contradiction here, but neither is there "one closely knit system" we find in Thomas Aquinas.

Luther is more radical than Paul and the distinctions between the redeemed and the damned are more pronounced, not least because he had seen perversions of Christian community in a way that Paul had not. What they share is an ambivalence about culture to the life of faith, but Luther had a distaste for the monastery that made him suspicious of that expression of radical Christianity.

"More than any great Christian leader before him, Luther affirmed the life in culture as the sphere in which Christ could and ought to be followed; and more than any other he discerned that the rules to be followed in the cultural life were independent of Christian or church law," Niebuhr observes. "Though philosophy offered no road to faith, yet the faithful man could take the philosophic road to such goals as were attainable by that way" (p. 174).

Niebuhr, however, argues against the Catholic caricature of Luther as claiming that his ambivalence about culture lapsed into indifference, that he viewed the same human act, the same cultural fact, as having no intrinsic value but for that imparted to them by faith in Christ and encounter with the believer. This may be true of some of Luther's followers, with dire consequences for the development of secularization, but not of Luther himself:

Luther's answer to the Christ-and-culture question was that of a dynamic, dialectical thinker. Its reproductions by many who called themselves his followers were static and undialectical. They substituted two parallel moralities for his closely related ethics. As faith became a matter of belief rather than the fundamental, trustful orientation of the person in every moment toward God, so the freedom of the Christian man became autonomy in all the special spheres of culture. It is a great error to confuse the parallelistic dualism of separated spiritual and temporal life with the interactionism of Luther's gospel of faith in Christ working by love in the world of culture [p. 179, emphasis mine].

The rise of autonomy as a central organizing value in modern society is surely the most anti-Christian development of the modern era.

As strange as that seems to those of us raised in the Catholic Church, there is no denying that the vision of the dualist is compelling. "Living between time and eternity, between wrath and mercy, between culture and Christ, the true Lutheran finds life both tragic and joyful," Niebuhr writes. I find life that way also. Yet it is also clear that this extrinsic valuation of culture when combined with the belief that law exists to restrict the reach of evil disposes both Paul and Luther to an acceptance of authoritarianism in civil affairs.

(Pixabay/klimkin)

Niebuhr goes on to examine Soren Kierkegaard, the great Danish existentialist, but his individualistic approach to these issues — "He assumes that he alone in Denmark is struggling hard to become a Christian," Niebuhr archly comments — need not detain us. What is important, especially for Americans in our day, are Niebuhr's warnings about the potential pitfalls of dualism:

Dualism may be the refuge of worldly-minded persons who wish to make a slight obeisance in the direction of Christ, or of pious spiritualists who feel that they owe some reverence to culture. Politicians who wish to keep the gospel out of the realm of "Real-Politik," and economic men who desire profit above all things without being reminded that the poor shall inherit the kingdom, may profess dualism as a convenient rationalization. But such abuses are no more characteristic of the position itself than are the abuses associated with each of the other attitudes [p. 184].

Still, in our day and in our culture, where the dangers of the cloister have long since subsided, it is dualism that has the greatest potential to harbor frauds and a foundational deficit in reconciling the different dogmatic claims of orthodox Christianity.

"There seems to be a tendency in dualism, as represented by both Paul and Luther, to relate temporality and finiteness to sin in such a degree as to move creation and fall into very close proximity, and in that connection to do less than justice to the creative work of God," Niebuhr poignantly observes. "These thoughts lead to the idea that in all temporal work in culture men are dealing only with the transitory and the dying. Hence, however important cultural duties are for Christians their life is not in them: it is hidden with Christ in God. It is at this point that the conversationist motif, otherwise very similar to the dualist, emerges in distinction from it" (p. 188-189). And so now we turn to the last of the resolutions of the culture question, those who see Christ as the transformer of culture.

Those who represent this conversionist motif — Niebuhr cites St. John the Evangelist, Augustine, the Christian socialist F.D. Maurice — "belong to the great central tradition of the church." They are not radicals, nor accommodationists, believing against the former that culture, too, is under God's sovereign rule, and against the accommodationists that Christ "forgives the most hidden and proliferous sin, the distrust, lovelessness, and hopelessness of man in his relation to God. And this he does not simply by offering ideas, counsel, and laws; but by living with men in great humility, enduring death for their sakes, and rising again from the grave in a demonstration of God's grace rather than an argument about it" (pp. 190-191).

The conversionists' more hopeful and positive attitude toward culture is what distinguishes them from the dualists, and Niebuhr attributes it to three theological convictions.

First, and markedly different in their views of creation from that of the dualists, "the creative activity of God and of God-in-Christ is a major theme, neither overpowered by nor overpowering the idea of atonement" (p. 192). Niebuhr notes that when Paul confessed that "in Christ all things were created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible ... all things were created through him and for him" (Colossians 1:16), this is not actually one of Paul's major themes; it is "used mostly to introduce the great theme of reconciliation."

Advertisement

The second theological conviction that Niebuhr attributes to the conversionists has to do with "the nature of man's fall from his created goodness." Whereas dualism "often brings creation and fall into such close proximity that it is tempted to speak in almost Gnostic terms, as if creation of finite selfhood or matter involved fall," the conversionist only walks with the dualist in agreeing that man had had a radical fall. "But he distinguishes the fall very sharply from the creation, and from the conditions of life in the body. It is a kind of reversal of creation for him, and in no sense its continuation." The key word for the conversionist is corruption: "Man's good nature has been corrupted; it is not bad as something that ought not to exist, but warped, twisted, and misdirected" (p. 194).

The third theological conviction that animates the conversionist flows from the first two: "a view of history that to God all things are possible in a history that is fundamentally not a course of merely human events but always a dramatic interaction between God and men. ... history is the story of God's mighty deeds and of man's responses to them."

The Gospel of John has some seemingly divergent interpretations of the Christian event. The radical Christian emphasis on separation from the world, or at least from the synagogue, is pronounced. But the "basic ideas of conversionist thought are, however, all present in it; and the work itself is a partial demonstration of cultural conversion, for it undertakes not only to translate the gospel of Jesus Christ into the concepts of its Hellenistic readers, but also lifts these ideas about Logos and knowledge, truth and eternity, to new levels of meaning by interpreting them through Christ" (p. 196-197).

The conversionist values creation more highly than the dualist who, as noted, tends to place creation and fall too closely to one another, becoming suspicious of matter per se. John the Evangelist could not be accused of Panglossian sensibilities, but "John could not say more forcefully that whatever is is good ... the physical, material and temporal are never regarded as participating in evil in any peculiar way because they are not spiritual and eternal. On the contrary, natural birth, eating, drinking, wind, water, and bread and wine are for this evangelist not only symbols to be employed in dealing with the realities of the life of the spirit but are pregnant with spiritual meaning" (p. 197). Dualism gives way to contradiction, and contradiction only gives way before the powerful intervention of God:

The corruptness of the world appears in its relation to the Son of the Father, and not only in its attitude toward the Father of the Son. Christ, the lover of God, loves the world; it responds to his love with rejection and hatred. ... He comes to give life; men give him death. He comes to tell men the truth about themselves; they lie about him. He comes to testify about God; the world answers, not with its corroborative testimony about its maker and redeemer, but with references to its lawgivers, its holy days, and its culture. "He came unto his own and his own received him not" [p. 199].

The principal effect of the Christ event is to awaken in God the full extent of his mercy. Niebuhr quotes British theologian Edward Hoskyns: "The theme of the Fourth Gospel is the nonhistorical that makes sense of history, the infinite that makes sense of time, God, who makes sense of men and is therefore their Savior" (p. 201). Christ transforms everything about human culture, and John gives voice to the universal reach of Christ's dominion more than any other evangelist, but John, as if hedging his bet, encourages separatism from the hostile and foreign world.

It is no surprise that St. Augustine is both a commanding and perplexing figure, in regard to this conversation as well as to others. Like John the Evangelist, Augustine must define his sense of the question by defining himself against both the exclusive Christians and the accommodationists, and in Augustine as in John "this motif is accompanied in his thought by other ideas about the relations of Christ and culture" (p. 207).

Niebuhr notes that Augustine's interest in monasticism evidences a disposition toward the radical Christians while his Neoplatonism shows him to be capable of assimilationism, and yet the Thomists are not wrong to insist he is one of them for the many ways his thought overlaps with theirs. "Once more, then, we deal with a man who is much more than representative of a type" (p. 208). Perhaps we columnists must reduce our intellectual opponents to caricature now and then, but I hope all who exercise pastoral ministry in the church will reread that last sentence and think of it before they speak out against any fellow Christian. A friend told me that this issue of typology dominated the reviews of the book when it came out, and whether or not Niebuhr was unfairly favoring one type over another. We can look at this more on Friday.

Niebuhr, however, is clear and convincing that Augustine belongs with the conversionists more than he does with any other group:

Nevertheless, the interpretation of Augustine as the theologian of cultural transformation by Christ is in accord with his fundamental theory of creation, fall, and regeneration, with his own career as pagan and Christian, and with the kind of influence he has exercised on Christianity. The potential universalism of his theory cannot be gainsaid. Augustine not only describes, but illuminates in his own person, the work of Christ as converter of culture. The Roman rhetorician becomes a Christian preacher, who not only puts into the service of Christ the training in language and literature given him by his society, but, by virtue of the freedom and illumination received from the gospel, uses that language with a new brilliance and brings a new liberty into that literary tradition [p. 208].

And again, and further explaining the difference of this motif from that of the dualists:

Christ is the transformer of culture for Augustine in the sense that he redirects, reinvigorates, and regenerates that life of man, expressed in all human works, which in present actuality is the perverted and corrupted exercise of a fundamentally good nature; which, moreover, in its depravity lies under the curse of transiency and death, not because an external punishment has been visited upon it, but because it is intrinsically self-contradictory. ... How Augustine, after many false starts in speculative and practical reasoning, was enabled to begin with God, Father, Son and Holy Spirit, and to proceed thence to the understanding of the self and the creature, is the story of his Confessions. After he made this beginning — or after his life was so rebegun — he saw that all creation was good, first as good for God, the source and center of all being and value, and secondly as good in its order, with the goodness of beauty and of the mutual service of the creatures [p. 109-110].

This esteem in which Augustine held creation is often overlooked because of his severe emphasis on sin, but you cannot understand what Augustine meant by sin unless you first grasp his view of creation. Sin occurs when "the will abandons what is above itself, and turns to what is lower, it becomes evil — not because that is evil to which it turns, but because this turning itself is wicked" (City of God, XII, 6).

"Scenes from the Life of St. Augustine of Hippo" (circa 1490, detail) by Master of St. Augustine (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In one of the finest sentences of the entire book, Niebuhr explains this central doctrine of original sin as Augustine conceived it: "This primal sin, which is more significantly named the first sin of man than the sin of the first man, may be variously described as falling away from the word of God, as disobedience to God, as living according to man and as pride, for 'what is pride but the craving for an undue self-exaltation?' " (p. 211). Augustine has gotten a bad rap in our progressive era precisely because of his insistence on the pervasiveness of sin, but I confess I find his description of original sin more compelling with each year the good Lord gives me to collect evidence one way or the other. And it is clear that Augustine understood the social quality of sin as well as any modern.

The remedy for this squalid state of disordered affairs is, of course, Jesus Christ, "who as God is our end and as man is our way." And the remedy is as comprehensive as it is elusive.

"Everything, and not least the political life, is subject to the great conversion that ensures when God makes a new beginning for man by causing man to begin with God," Niebuhr writes of Augustine's worldview. "Were one to pursue Augustine's conversionist ideas only, one might represent him as a Christian who set before men the vision of universal concord and peace in a culture in which all human actions had been reordered by the gracious action of God in drawing all men to himself, and in which all men were active in works directed toward and thus reflecting the love and glory of God. Augustine, however, did not develop his thought in this direction" (p. 214-215).

A funny thing happened on the way from the forum. Looking around at the culture of his time, Augustine did not see regeneration in Christ but decline and dissolution:

Why the theologian whose fundamental convictions laid the groundwork for a thoroughly conversionist view of humanity's nature and culture did not draw the consequences of these convictions is a difficult question. It may be argued that he sought to be faithful to the Scriptures with its parables of the last judgment and the separatist ideas in it. But there is also a universal note in the Scriptures; and faithfulness to the book does not explain why one who otherwise was always more interested in the spiritual sense than in the letter, not only followed the letter in this instance but exaggerated the literal sense. The clue to the problem seems to lie in Augustine's defensiveness [p. 216].

Niebuhr is not using "defensiveness" in any pedestrian, psychological sense of the term. He makes a defense of divine justice a centerpiece in working out his confession of sin and divine grace. He defends the Catholic Church from pagan critics and of the institutions of Christian society from challenges within and without. Acutely aware of the dissolution of the culture all around him, Augustine becomes a churchman of the highest order:

He often tends to substitute the Christian religion — a cultural achievement — for Christ; and frequently deals with the Lord more as the founder of an authoritative cultural institution, the church, than as savior of the world through the direct exercise of his kingship. Hence also, faith in Augustine tends to be reduced to obedient assent to the church's teachings, which is doubtless very important in Christian culture but nevertheless is no substitute for immediate confidence in God [p. 217].

Niebuhr's distance from Catholicism is evident here. As in other cases, he sees only distinctions and contrasts where the Catholic habit of mind is, as a friend emailed this week after this series began, "more of a path of humanism, grounded in the Incarnation. It's less oppositional and tends to include, incorporate, and connect."

"Baptism," an 1870s painting by William P. Chappel depicting the Second Great Awakening (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Before we leave this conversionist motif, it is worth considering Niebuhr's treatment of Jonathan Edwards, the leading 18th-century theologian of the Great Awakening. Niebuhr credits Edwards with becoming "the founder of a movement of thought about Christ as the regenerator of man in his culture" even if that movement has gone astray: "It has never wholly lost its momentum, though it was often perverted into banal, Pelagian theurgisms in which men were concerned with the symptoms of sin, not its roots, and thought it possible to channel the grace and power of God into the canals they engineered" (p. 220).

Niebuhr goes on to examine Maurice, the 19th-century Christian socialist, who may yet prove a consequential figure in American Christian intellectual life if Sen. Bernie Sanders becomes the Democratic nominee for the presidency. Even without that prospect, Maurice's observation — "When I began to seek God for myself, the feeling that I needed a deliverer from an overwhelming weight of selfishness was the predominant one in my mind" (p. 222-223) — still rings true in our culture. (Or did I just have a TMI moment?)

I admire Maurice's incipient universalism, which seems akin to that of the great Catholic Swiss theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar, when he writes: "I cannot believe that He will fail with any at last; if the work were in other hands it might be wasted; but His will must surely be done, however long it may be resisted" (p. 226). Such a sentiment could be dismissed as overly optimistic but his choice of verb — resist — indicates that Maurice was a keener student of humankind than many other 19th-century thinkers, whether they wrestled with the Gospel of Jesus Christ or not.

So, Christ as transformer of culture is the last of the five responses Niebuhr identifies for resolving the problem of Christ and culture. If you, dear reader, have made it this far, I commend and thank you. Tomorrow, I shall offer a few comments on the whole, designed more to stimulate further discussion than to draw any conclusions.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest. Sign up and we'll let you know when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.