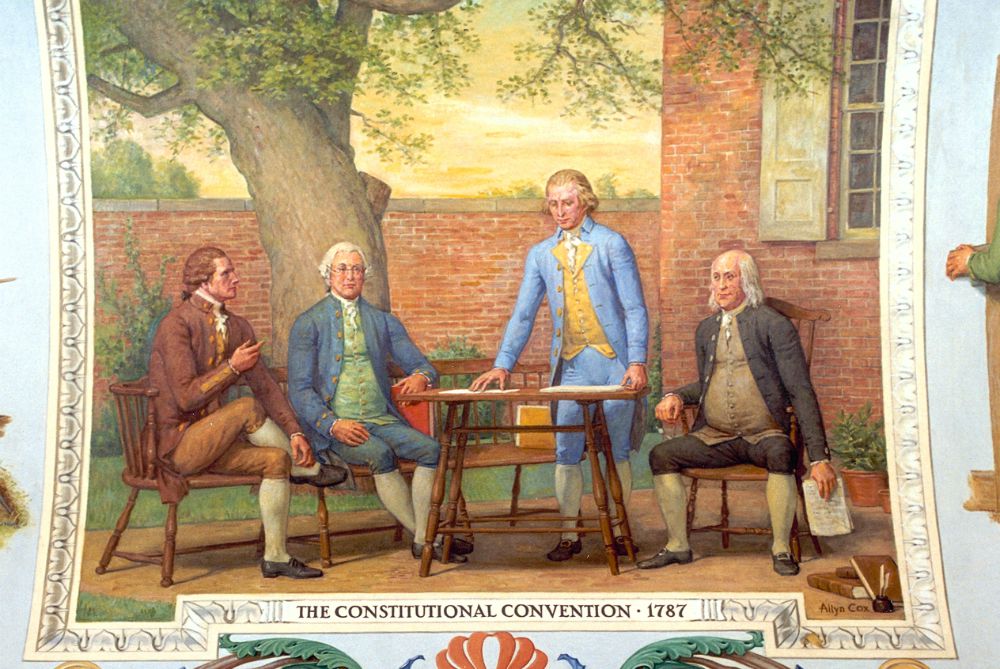

Detail of "The Constitutional Convention, 1787" mural by Allyn Cox in the Great Experiment Hall of the U.S. Capitol, painted 1973-74, depicting Alexander Hamilton, James Wilson, James Madison, and Benjamin Franklin (Wikimedia Commons/Architect of the Capitol)

The bulk of the post-midterm analysis has focused on the brewing fights between a Democratic House and President Donald Trump. He threatened to initiate investigations of House members if the House does its job and conducts oversight of his administration. At least Nixon had the decency to make his threatened abuse of power in private!

And within the Democratic Party, the debate has begun about how to shape its own political stances in the next two years with a hope of preventing Trump from securing a second term. I am betting the Democrats will make the wrong choice and embrace the social liberalism of the donor class along both coasts, overshadowing the unifying potential of economic issues, and they will end up nominating Sen. Cory Booker or Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand. Trump will win in a rout. But that is a nightmare for another day.

Beneath the ballot issues and the personalities, some profound issues of democratic legitimacy were highlighted on Tuesday, and it is far from clear that our country and its Constitution will prove capable of withstanding the questions those issues raise.

On the one hand, it was a very good sign that voters in three states voted to enact some kind of independent commission to conduct redistricting after each decennial census. Colorado, Michigan and Missouri voters, while disagreeing about much else, agreed to create non-partisan processes — Missouri voted for a computer model over a commission, but the effect should be the same — so that politicians no longer have the luxury of choosing their voters in advance of the election. In Utah, a similar measure is too close to call, but the vote to take politics out of redistricting is slightly ahead.

Partisan redistricting has helped the Republicans dominate the last decade politically after their big win in the 2010 midterm elections. Curiously, the effort to end it is unofficially led by a Republican, former California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. I have never been a fan of the "Austrian Oak," not as an actor nor as a politician — but something about the process rubbed him the wrong way and he decided to try and fix it. In 2008, California voters passed a referendum creating an independent commission to draw state legislative lines, and in 2010, a similar measure for congressional lines. In 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a similar scheme in Arizona. Seven states in all use a non-partisan or bipartisan commission, although one of them, in Montana, has an easy task, as the state has only one member of Congress. An eighth state, Iowa, uses nonpartisan staff to propose the maps, but the legislature then votes on the final proposal.

Advertisement

Tuesday saw one of the congressional chambers switch hands, but it is still remarkable, and worrisome, that only about 70 out of 435 congressional races were really races at all. The others were all "safe" seats because the party that controlled the redistricting, or both parties working together, arranged the districts to make them "safe" for the incumbents. The hope is that if districts are drawn without consideration of helping incumbents have an easy shot at reelection, there will be more competitive races and more voters will come to recognize that their vote does matter. This has proved to be the case. Pennsylvania had a court-imposed redistricting this year and Democrats flipped four seats to blue while the GOP took one seat previously held by a Democrat. That is democracy in action. The heaviest loss for the both the Democrats and democracy Tuesday night was the Florida governor's race: The GOP will control the redistricting process completely in the fast-growing state, which will be sure to gain House seats after the next census.

The Senate can't be redistricted, but it is so constructed that it heavily tilts political power towards more rural, and currently red, states. Tuesday night, more than 40 million votes were cast for Democratic Senate candidates, while GOP candidates garnered more than 31 million. Yet the Republicans picked up two, probably three, seats. It should be noted that because of California's non-partisan primary system, this year both of the Senate candidates were Democrats so more than six million votes were cast for Democrats in that one state alone. Still, you see the problem. A voter in Wyoming has 68 times the representation in the upper chamber of Congress than a Californian does.

According to a study by Baruch College's David Birdsell, by 2040, 70 percent of all Americans will live in the 15 largest states. That means that 70 percent of the nation's senators will be selected by only 30 percent of the population. At some point, the voters of the large states will demand change.

That tilt bleeds into the Electoral College. For 200 years, the winner of the popular vote was almost always the winner of the Electoral College. Only three times did the winner not win the popular vote, and in one instance, 1824, the election was thrown into the House of Representatives, and in another, 1876, a backroom deal ending Reconstruction cost the Democrat Samuel Tilden the presidency. But twice in the past 18 years, in 2000 and 2016, the new president got fewer votes than the candidate he defeated.

Constitutional legitimacy cannot sustain itself forever without democratic legitimacy. Yet in the current political climate, who would dare to open such foundational issues? Can you imagine what mischief a constitutional convention could cause? We Americans, so proud of our pragmatism, always assume that every problem has a solution. It is a naive assumption. This conundrum may be to the 21 century what slavery was to the 19th, the issue upon which the Union is broken.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest: Sign up to receive free newsletters and we'll notify you when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.