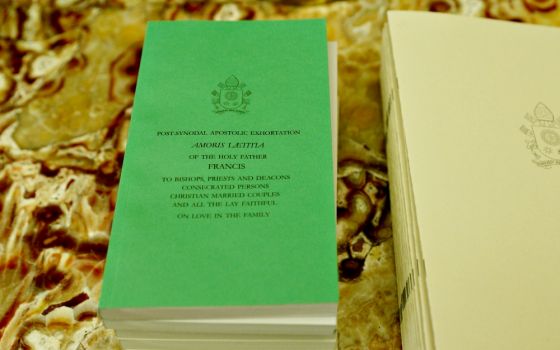

Yesterday, I wrote about the guidelines for the implementation of Amoris Laetitia issued by Archbishop Charles Chaput for the Archdiocese of Philadelphia. I took issue with some of the guidelines as not being true to the text of Amoris, and for not recognizing the consensus that was achieved at two synods but stating the minority view as if it had prevailed.

This morning, Civilta Cattolica published an interview that Cardinal Christoph Schonborn, O.P., gave to Jesuit Fr. Antonio Spadaro about Amoris Laetitia. Here is the

A final note before looking at the interview. I am not fit to untie the theological thong on Cardinal Schonborn's ecclesiastical sandal. This man is a theological heavyweight, having been chosen by St. Pope John Paul II to serve as general editor of the Catechism, and a student of, and later collaborator with, Pope Benedict XVI. Those who claim Pope Francis is "confusing" or that he has turned his back on the magisterium of John Paul II must now ask themselves: If Cardinal Schonborn sees Amoris Laetitia as a legitimate development of doctrine, why do they resist? If he can discern lucidity in the pope's writings and sayings, why cannot they?

In the interview, Cardinal Schonborn states, "AL is an act of the magisterium that makes the teaching of the Church present and relevant today. Just as we read the Council of Nicaea in the light of the Council of Constantinople, and Vatican I in the light of Vatican II, so now we must read the previous statements of the magisterium about the family in the light of the contribution made by AL." He has reversed the order we hear from those who oppose Francis and have said that Amoris Laetitia must be read in the light of Familiaris Consortio, John Paul's 1981 exhortation on family life. This has been a near constant refrain at EWTN for example. In his guidelines, Archbishop Chaput stated, "As with all magisterial documents, Amoris Laetitia is best understood when read within the tradition of the Church's teaching and life" which at least does not give hermeneutic precedence to the past, but still the difference in emphasis is noteworthy.

Cardinal Schonborn states, "We are led in a living manner to draw a distinction between the continuity of the doctrinal principles and the discontinuity of perspectives or of historically conditioned expressions. This is the function that belongs to the living magisterium: to interpret authentically the Word of God, whether written or handed down." Here, I find nothing in Archbishop Chaput's guidelines that contradict the cardinal's insight. I do think those like Cardinal Raymond Burke, Fr. Gerald Murray of EWTN, George Weigel, and others, who have spoken endlessly about the "irreformable" doctrines of the Church have to put on their thinking caps anew.

In response to another question, the cardinal quotes from Amoris Laetitia:

The Church possesses a solid body of reflection concerning mitigating factors and situations. Hence it can no longer simply be said that those in any 'irregular' situation are living in a state of mortal sin and are deprived of sanctifying grace. More is involved here than mere ignorance of the rule. A subject may know full well the rule, yet have great difficulty in understanding 'its inherent values,' or be in a concrete situation which does not allow him or her to decide differently and act otherwise without further sin. As the Synod Fathers put it, 'factors may exist which limit the ability to make a decision.'

Compare that with this in Archbishop Chaput's reflection on gay couples:

But two persons in an active, public same-sex relationship, no matter how sincere, offer a serious counter-witness to Catholic belief, which can only produce moral confusion in the community. Such a relationship cannot be accepted into the life of the parish without undermining the faith of the community, most notably the children.

The phrase "no matter how sincere" seems at odds with this section of Amoris quoted by the cardinal, does it not? And, indeed, the whole tenor of this passage in the guidelines seems at odds with the approach the cardinal is trying to emphasize.

On this point, and again raising the question about the correct understanding of Pope John Paul II, Schonborn states:

John Paul II already presupposes implicitly that one cannot simply say that every situation of a divorced and remarried person is the equivalent of a life in mortal sin that is separated from the communion of love between Christ and the Church. Accordingly, he was opening the door to a broader understanding, by means of the discernment of the various situations that are not objectively identical, and thanks to the consideration of the internal forum.

As I noted yesterday, Archbishop Chaput did not mention the internal forum at all, but reading this passage, I had a naughty thought. You recall the refrain in the theme of the movie "Who ya gonna call? Ghostbusters!" When considering the correct interpretation of the magisterium of St. Pope John Paul II, who ya gonna call? The man who collaborated with him on the Catechism or, say, George Weigel or Cardinal Burke?

My favorite section of the interview is this:

With great perspicacity, Pope Francis asks us to meditate on 1 Cor 11:17-34 (AL 186), which is the most important passage that speaks of eucharistic communion. This allows him to relocate the problem, and place it where Saint Paul places it. It is a subtle way of indicating a different hermeneutic in response to the recurrent questions. It is necessary to enter into the concrete dimension of life in order to 'discern the body,' begging for mercy. It is possible that the one whose life is in accordance with the rules lacks discernment, and eats his own judgment.

This is key for a variety of reasons. The "different hermeneutic" at work here is, I believe, a shocker to those who invoke John Paul II to condemn Pope Francis because they never fully grasped the influence of Communio theology on John Paul II. With apologies to people who do theology with a license and full time, and who grasp these issues far better than myself, it seems to me that the "official interpreters" of John Paul II in the American context always had excessive recourse to natural law theory, and exclusively to the John Finnis and Germaine Grisez understanding of natural law theory, and they never really grasped the challenges of a Balthasar or a deLubac. This sense of the difference is confirmed for me by this passage in the interview in which the cardinal states:

We have sometimes spoken of marriage so abstractly that it loses all its attractiveness. The Pope speaks very clearly: no family is a perfect reality, since it is made up of sinners. The family is en route. I believe that this is the bedrock of the entire document. This way of looking at things has nothing to do with secularism, with Aristotelianism as opposed to Platonism. I believe, rather, that it is the biblical realism, the way of looking at human beings that scripture gives us.

This, I would submit, is the conversation the bishops should be having, and not only in regard to marriage: How does a biblical realism alter the way we look at the issues facing the Church? How does it permit us to understand abstract truths, but not to lose the reality of human life, dignified by the Incarnation, in those abstractions? This is what the USCCB's ad hoc committee led by Archbishop Chaput to study the implementation of Amoris Laetitia should focus on, and indeed, it should inform the redrafting of "Faithful Citizenship" and every other text that comes from the conference.

It is not only that winds of change are blowing in the Church of Pope Francis. I would submit that winds of real faith are blowing too. Abstractions have their place, but a pastor knows that what is real is not the abstraction but the human life of the pilgrim Christian. And, of course, the pilgrim Church. Looking at the differences between the guidelines and the interview, I was reminded of something a friend once said when comparing Michelangelo's "David" with that of Bernini. "Both are very beautiful," he said, "but when you walk into the room at the Borghese and confront the Bernini, you duck." The vision of Pope Francis is alive and buoyant. It recognizes the formal rules and the beauty they possess. But, the vision is focused on the real, not the abstract, and this is the change that seems to make some bishops and theologians very uncomfortable.

[Michael Sean Winters is NCR Washington columnist and a visiting fellow at Catholic University's Institute for Policy Research and Catholic Studies.]