Historian Paul Collins didn’t intend it as such, but his The Birth of the West is partially an antidote to Thomas Cahill’s informative and entertaining, if overweening, How the Irish Saved Civilization.

THE BIRTH OF THE WEST: ROME, GERMANY, FRANCE, AND THE CREATION OF EUROPE IN THE TENTH CENTURY

THE BIRTH OF THE WEST: ROME, GERMANY, FRANCE, AND THE CREATION OF EUROPE IN THE TENTH CENTURY

By Paul Collins

Published by PublicAffairs, $29.99

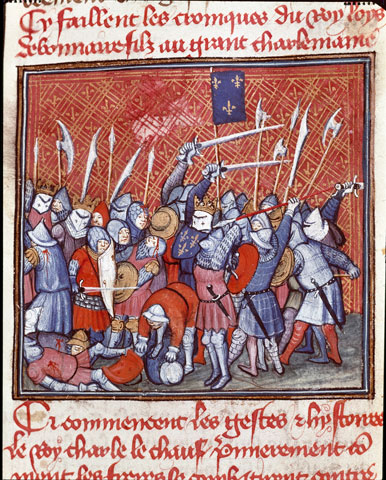

With Collins I cheated, something I rarely do with a book. I dove straight into Chapter 15: “Faith and Church in the Tenth Century.” I was looking for that fighting figurehead, Charles the Bald, the ninth-century Charles II, the Holy Roman Emperor. (He died in a place called Brides-le-Bain, which schoolboys translated as “brides in the bathtub.”) I needn’t have searched; Charles pops up regularly throughout the book.

Australian Collins, historian and former priest, has a masterly touch throughout, for he writes the book on the several levels. He describes Europe, physically. He tells us what we are looking at, the stage set of history, the extensive woodlands, the major massifs and plateaus. All the while he is populating this landscape. This is truly history from the bottom up, layering the terrain. This is Dark Ages cities when Rome’s population, possibly once as high as 800,000, was now between 25,000 and 35,000. Yet Collins’ history is telling that though the ages were dark, not all the lights had been turned off. What we are receiving from Collins’ sure hand is what happened after the fall of Rome. Not much, until a later ninth-century flickering, and then candles being lit across the 10th century.

We meet Alberico early. He was a land-grabbing murderer whose land included Rome. There were, in the ninth century, three popes simultaneously.

Alberico’s favorite was the ruling Sergius III. And if the others began to disappear from the scene, well, there’s also plenty of sexual scuttlebutt to counterbalance the brutality.

This is not to suggest Collins is taking history lightly. History itself is pretty light at times. The Harvard-trained theologian with a doctorate in history from Australia’s National University is attempting to give some form to the Dark Ages’ shadows by introducing those who wanted to bring order to a disorganized, disintegrated Europe barely recognizable as a place with boundaries -- other than language and patois and geographical boundaries like mountain chains and broad rivers.

His chapter on Islam and the Muslim-Christian coexistence under Islamic domination in Spain is a story unto itself. His Anglo-Saxon Britain and Celtic lands excursions are like packaged tours in time. This is an intriguing 395-page read that gradually comes together at the end as Collins pulls on all the threads to tie into a fine knot. (And, yes, the Collins’ name may seem familiar to you. He was a parish priest in Australia for 33 years, well-known to NCR. He resigned after battling with the papacy and went on to write a book on all those who similarly jousted with the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, The Modern Inquisition. Which is not why he’s reviewed here.)

To conclude with Collins and Thomas Cahill, their Dark Ages starting points are not dissimilar.

Collins opens with the anonymous Irish monk in his Bangor (Northern Ireland) monastery, who, fearing the Vikings, wrote in the margins of the grammar book he was studying:

The bitter wind is high tonight

It lifts the white locks of the sea

In such wild winter storm no fright

Of savage Viking troubles me.

It was a storm a hundredfold times more wild that swept toward Japan in 2011 and is the focal point of Sean McDonough’s Fukushima on the earthquake and tsunami’s second anniversary. Nor is McDonough’s link to that anonymous monk as tenuous as the 12 centuries between them suggests. McDonough is a Columban monk, too.

FUKUSHIMA: THE DEATH KNELL FOR NUCLEAR ENERGY?

FUKUSHIMA: THE DEATH KNELL FOR NUCLEAR ENERGY?

By Sean McDonough

Columba Press, $23.95

McDonough, as always in his books, quickly gets down to work. He writes compendious accounts in a tightly packed format across a range of environmental and ecological issues. Here, he’s working from secondary sources, but he selects carefully and forcefully the events of the Fukushima meltdown and dwells intelligently on the meltdown’s impact on the Japanese people, Tokyo’s politics and corporate maneuverings. From there he opens up the global nuclear energy discussion.

Some countries aren’t listening. Vietnam for one. Yet, while McDonough has his preferences and concerns, he is, like Collins, really writing history. If Collins takes his by lifting up the tombstones of time, McDonough’s is from the packaged organic foods section. Still fresh.

He selects from North and South. Kenya is considering a $10 billion nuclear plant on its Athi Plains, Nigeria is negotiating with the Russian state nuclear industry, Egypt’s nuclear plans are temporarily on hold given the turmoil, and India is set to open two new plants.

Not only new plants, but Fukushima takes us to the old plants and their various explosions and continuing meltdown potential.

The author dips with some certainty into Britain’s foul-ups and cover-ups. Britain’s aging plants are leaking, but governments allied to the industry love nuclear power. McDonough provides the backdrop to the British government’s attempt to downplay the seriousness of the Fukushima meltdown, with one government official writing, “We need to ensure that the anti-nuclear chaps and chapesses do not gain ground on this. We need to occupy the territory and hold it. We really need to show the safety of nuclear.”

NCR has a four-decade stake in this discussion. From 1980 on, under editor Tom Fox, this became the anti-nukes newspaper. The immediate threat was the Cold War. The secondary threat, the unreliable reactors themselves, started with the Three-Mile Island accident just before Fox took office. (I have a personal stake. I’ve covered this beat from the Native Americans dying from exposure to uranium mining, to the corporate bid to reopen uranium drilling and pumping in America’s Four Corners, to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s lessening of new reactor public hearing requirements -- in the “quiet years” when no one was watching or listening much -- and a rundown on an aging nuclear plant in Calvert Cliffs, Md.)

Nuclear energy remains a terror. Not just in the hands potentially of terrorists, but also in the hands of elected governments tied to the industry. (And, yes, I know Sean McDonough. But at my age, I’ve been around for so long I’ve probably met, interviewed, know or dealt with some 10-20 percent of the Catholics who write nonfiction.)

McDonough’s is the current compendium of where we are nuclear-threatwise. It is important, and chilling. Nuclear terrors are the new Vikings threatening all our shores and inland fastnesses. Dark Ages indeed.

[Arthur Jones is NCR books editor.]