People take part in an opposition rally to demand the resignation of Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko and to protest against police violence Nov. 30 in Minsk, Belarus. The Catholic bishops in Belarus said the country's "unprecedented socio-political crisis" was worsening four months after the disputed reelection of Lukashenko. (CNS/Reuters)

When two priests were arrested in Belarus on Dec. 8 amid continued protests against the authoritarian rule of President Alexander Lukashenko, there were fears of a full-scale campaign against the minority Catholic Church.

Jesuit Fr. Viktar Zhuk and Greek Catholic Fr. Alyaksei Varanko, both from Vitebsk near Belarus' northeastern border with Russia, were confined under house arrest a day later, but were told they faced charges of "participating in unauthorized events."

They were only the latest Catholic clergy to face sanctions, three months on from the forced exile of their Church's veteran leader, Minsk and Mohilev Archbishop Tadeusz Kondrusiewicz.

"There's real repression here now — the authorities are shocked at the level of Catholic engagement and struggling to contain it," Kaciaryna Laurynenka, a Catholic theologian teaching church history and canon law in Vitebsk, told NCR.

"There were hopes last summer that everything would change radically in a month or two if enough people took to the streets," said the theologian. "Today, it's difficult to foresee what will happen. But if you're active as a Catholic, you can expect trouble."

In a message to Catholics at his St. Vladislav parish, Zhuk said he was "grateful and touched" by their support and urged them to pray "for a Belarus without violence, where human dignity is respected."

Archbishop Tadeusz Kondrusiewicz (CNS/Bob Roller)

Meanwhile, in a rare interview the same day, Kondrusiewicz defended the role of Catholic clergy, expressing disappointment that his calls for dialogue and negotiation had been ignored.

"Neither I nor anyone from our church has ever called for protests," the exiled president of the country's bishops' conference assured Poland's Catholic Information Agency, KAI. "However, we will uphold the church's social teaching and call for the peaceful resolution of protests, while always opposing lies, violence and injustice."

In today's turbulent conditions, most Catholics would concur that making predictions is hazardous in Belarus, a former Soviet republic bordering Russia to the east and Poland to the west, now caught between popular demands for Western-style democracy and concerns for regional stability.

"The campaign against our church is constant — from the very beginning we were presented as the main enemy and attempts made to link the church with a political struggle," Fr. Yuri Sanko, the bishops' conference's spokesman, told NCR.

"We can only keep on repeating that we're not politicians and there's no reason to fear us," he said. "But if events are reaching such a head that our priests are arrested, the church will protect its own."

Protests erupted after Belarus' Aug. 9 presidential election, when Lukashenko, in power since 1994, was declared the winner with an improbable 80% of votes.

With four dioceses and around 500 parishes, the Catholic Church claims around 15% of the country's 9.4 million inhabitants as members, and quickly found itself drawn into the drama as its leaders condemned brutal overreactions to the protests by Lukashenko's security forces.

A plainclothes law enforcement officer tries to detain a student during a protest against presidential election results Sept. 1 in Minsk, Belarus. (CNS/Tut.By via Reuters)

Clergy from Belarus' larger Orthodox Church, which is linked to Russia's Moscow Patriarchate, also spoke out against the repression, surprising a regime accustomed to a quiescent stance by local churches.

The Orthodox voice was partly reined in by the appointment of a new leader, Metropolitan Veniamin, who has avoided direct criticism of either side in the conflict.

In November, the Orthodox Church's press secretary, Fr. Sergei Lepin, was forced to resign after denouncing the "satanic trampling of flags and icons" by police during one of many Minsk crackdowns.

But Catholic clergy have remained outspoken, despite a spectacular act of regime retaliation on Aug. 31, when Kondrusiewicz was barred by border guards from returning home after a routine visit to neighboring Poland.

The 74-year-old archbishop has since been based at the sanctuary of the Eucharistic miracle at Sokolka on Poland's Belarus border, remaining in daily internet and mobile phone contact with his archdiocese.

"Everything is in God's hands, so I'm optimistic," Kondrusiewicz told the KAI agency on Dec. 10. "If we're called today to carry the cross, we must carry it with confidence."

The fate of the archbishop, who became Belarus' first post-communist prelate in 1989, may also be in the hands of the Vatican. Archbishop Paul Gallagher, the Vatican's foreign minister, visited Minsk for talks with Lukashenko's officials in September.

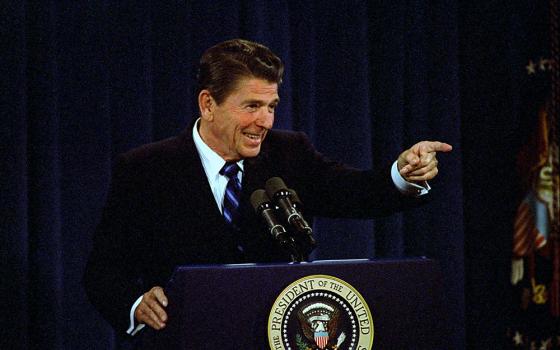

Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko attends a meeting Nov. 30 in Minsk, Belarus. (CNS/Maxim Guchek/BelTA, Reuters)

A new Vatican ambassador to Belarus, Croatian Archbishop Ante Jozic, also took office in mid-October, raising hopes of firm Vatican action once diplomatic courtesies were completed.

But any practical effects are still to be seen.

The Vatican's embassy in Minsk, known as a nunciature, did not respond to a Dec. 9 inquiry from NCR about the status of current negotiations between the church and the Belarusian government.

If talks between the Vatican and the regime are underway, Laurynenka said she regrets that church members are being kept in the dark.

Many were "surprised," she said, to see Jozic presenting his credentials and drinking champagne with Lukashenko, as Catholics protesting their beleaguered archbishop's mistreatment have been beaten and dispersed by regime thugs.

"Of course, in such a delicate situation, it's understood the nuncio has to act diplomatically," the Catholic lecturer told NCR. "But everyone is in shock at what's happened this year, and hoping someone will help sort the problems out. So far, we haven't seen anything to suggest this is happening."

In early December, Belarus's opposition leader, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, exiled in Lithuania since last August's election, bypassed the nunciature and sent a letter to Pope Francis, warning that clergy and laypeople from all denominations faced "persecution by the authorities."

Prayers from Francis might still "penetrate the armor-plated windows of police cars, militia shields and the disconnected internet," Tsikhanouskaya added.

For now, though, the anti-Catholic pressure looks set to continue.

Advertisement

In September, Sergei Naryshkin, Russia's Foreign Intelligence Service director, accused the United States of "interfering unceremoniously in the religious situation in Belarus," and of using the minority Catholic Church to undermine the state.

Lukashenko has since threatened to bar priests from Poland and Lithuania from coming to minister in Belarus, whose 480 Catholic clergy depend heavily on pastoral help from abroad.

More direct action has followed.

In November, Bishop Yuri Kasabutsky, the Minsk auxiliary standing in for the exiled Kondrusiewicz, was warned by prosecutors after leading a cathedral requiem for an artist, Raman Bandarenko, who died of injuries sustained after plainclothes police attacked him in a Minsk square.

People gather to mourn the death of anti-government protester Raman Bandarenko Nov. 12 in Minsk, Belarus. (CNS/BelaPAN via Reuters)

In a social media post, Kasabutsky said he had since been told criminal charges were being prepared against him. Yet the 50-year-old bishop remains unfazed, assuring Italy's Servizio Informazione Religiosa, or SIR, that he and other clergy would continue resisting regime efforts to "prohibit the truth."

Threats of arrest are real.

On Nov. 29, as over 300 Belarusian protesters were rounded up by police using tear gas and stun grenades, two other priests, Fr. Vyacheslav Barok from Rassony, and Fr. Vitaly Bystrov, another Greek Catholic, were detained for an "unauthorized event," and jailed for 10 days.

Bystrov had only recently taken over a parish in the western city of Brest, after its long-standing pastor, Fr. Igor Kondratiev, was similarly harassed last August for demanding the release of beaten citizens.

Fr. Siarhiej Hajek, apostolic visitor for Belarus' Greek Catholic minority, which maintains Eastern-rite traditions but is in communion with Rome, branded Bystrov's arrest a mark of "deepening absurdity," insisting he had only conversed with people on the street.

Meanwhile, in a Nov. 25 message, Belarus' Catholic bishops insisted their country had long been "known for tolerance and harmony between people of different faiths and nationalities," and re-endorsed a September appeal from the pope, urging the state authorities to "listen to the voice of fellow citizens," and meet "legitimate aspirations" of "full respect for human rights and civil liberties."

The U.S. and other Western governments have imposed travel and financial sanctions against Lukashenko's regime. In mid-November, following Bandarenko's killing, the 27-country European Union tightened these still further, after making clear it considered Lukashenko's election victory fraudulent and would not recognize him as "legitimate president."

Fr. Yuri Sanko, spokesman for the Belarusian Catholic bishops' conference (Provided photo)

Sanko, the bishops' spokesman, would not comment on the issue of sanctions, saying that it's up to Western governments to determine whether these will be "an effective form of action."

But the priest was adamant that Belarus' Catholic Church, however small and under-resourced, won't be scared into silence.

"No actions against us have the slightest intimidatory effect — they merely fuel further tensions," he told NCR.

"From the very outset, our bishops, priests and laypeople have seen their main challenge as being to sustain each other in a prayerful way, and this is the position we're upholding, hoping peace will return as soon as possible, and our country become truly democratic," said Sanko.

Kondrusiewicz has said he will formally submit his resignation to the pope, as required by canon law, when he turns 75 on Jan. 3.

Much will depend on whether Francis accepts the archbishop's departure, or chooses to confront the Lukashenko regime — either by extending Kondrusiewicz's term or by appointing Kasabutsky to replace him.

Whichever decision is made, the bishops' conference and the Minsk-Mohilev Archdiocese likely cannot carry on indefinitely with an absent leader.

The Catholic Church's Caritas charity said on Dec. 10 that it was providing food and shelter for the homeless in Minsk and other cities, in expectation of a winter humanitarian crisis, in one of many signs of the deteriorating situation.

"People who were optimistic about change have learned a painful lesson — that 26 years of rule cannot can't be undone in just a few days," Laurynenka told NCR.

"Though all Belarusians are expecting better things, this will all clearly go on longer than they expected, all of which should counsel against unplanned, ill-considered actions," she said.

[Jonathan Luxmoore covers church news from Oxford, England, and Warsaw, Poland. The God of the Gulag is his two-volume study of communist-era martyrs, published by Gracewing in 2016.]