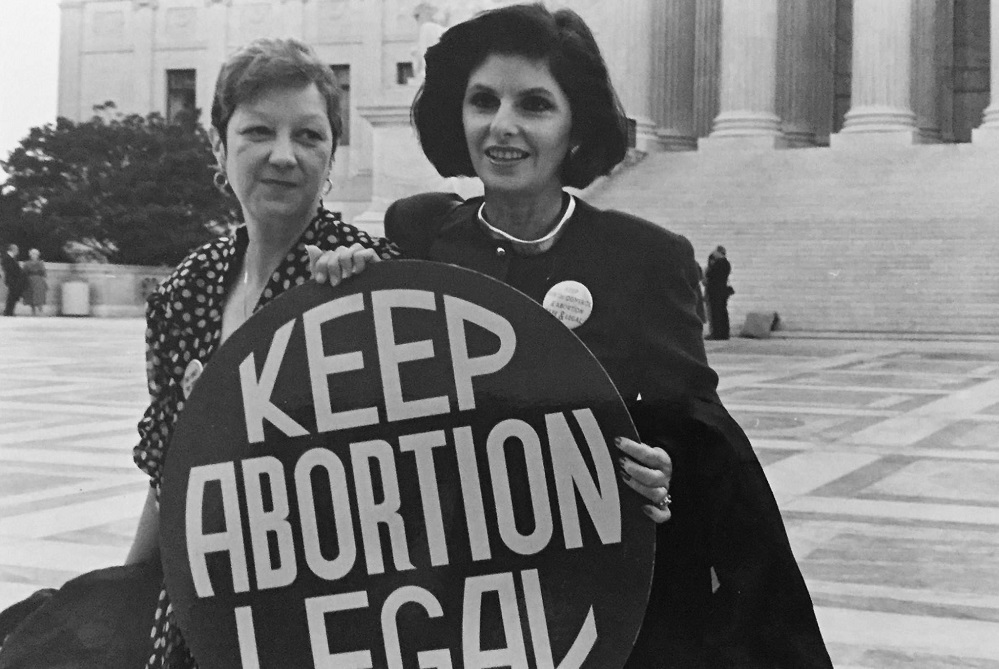

Norma McCorvey, left, who was "Jane Roe" in the 1973 Roe vs. Wade case, with her attorney, Gloria Allred, outside the Supreme Court in April 1989, where the court heard arguments in a case that could have overturned the Roe vs. Wade decision. (Lorie Shaull /Wikimedia Commons)

In 1969, a 21-year-old woman, pregnant for the third time, was referred to two lawyers seeking to challenge Texas' restrictive abortion laws. After a landmark decision overturning abortion law in all 50 states, the woman, Norma McCorvey, revealed herself as "Jane Roe" of Roe vs. Wade. In the 1990s, she assumed a role within the pro-choice movement, working at the front desk of an abortion clinic and gladly accepting invitations onto talk shows.

In 1994, after an unlikely friendship with an evangelical pastor, she emerged on TV from the house of Flip Benham, national director of Operation Rescue — baptized in the Holy Spirit and aflame with passion for the pro-life cause. She quickly became an icon of the pro-life movement, a regular fixture in anti-abortion advertisements, legislative hearings and protests. In 1998, she converted, this time with less fanfare, to Catholicism under the guidance of Fr. Frank Pavone, who would officiate at her funeral in 2017.

Over the weekend, a new documentary was released with footage of McCorvey throwing doubt on that transition, which she calls "an act." "I think it was a mutual thing," she says in the documentary. "I took their money and they took me out in front of the cameras and told me what to say." She also purports to be pro-choice: "If a young woman wants to have an abortion — fine. That's no skin off my ass. You know, that's why they call it 'choice.' "

McCorvey's description of her treatment by the pro-life movement has a striking resemblance to comments she made earlier about her treatment at the hands of pro-choice activists. In 2000, she claimed to have been "used and exploited in the women's movement and the Supreme Court of the United States."

"I never got the opportunity to speak for myself in my own court case," she told the Senate in 2005. "I believe that I was used and abused by the court system in America." She complained that her lawyers had used her for their own purposes, rather than giving her the help she needed, whether financial or vocational. The feeling was mutual, according to a pro-choice activist quoted in a 2013 Vanity Fair profile: "I think it's accurate to say that [we] were manipulating Norma and that Norma was manipulating us."

It's difficult to know how Norma McCorvey actually felt about abortion, or how well-formed her opinions actually were.

Although held up as a trophy by some, McCorvey was long considered suspect by activists and commentators. In 2010, her long-time partner described her as a "phony." In 2013, Vanity Fair described her as "less pro-choice or pro-life than pro-Norma." Benham, the man who converted her to Christianity, told the magazine: "She just fishes for money." In 2016, Sarah Weddington, her attorney from the 1970s, said she believed McCorvey had switched positions for the money. In constant financial trouble, she alternated between applying for food stamps and traveling the world on speaking tours, from the UK to New Zealand.

In this light, it's not surprising that McCorvey would make comments casting doubt on her previous statements. It's difficult to know how she actually felt about abortion, or how well-formed her opinions actually were. It's hard to weigh 11 years of pro-life expressions of belief against one comment on "choice" with an Australian filmmaker. There also appears to be no suggestion in the documentary that she renounced her religious beliefs.

This revelation does, however, call to mind the dangers of social activism fueled by celebrity conversions, a phenomenon that exists nowhere more than in America. The pro-life movement has had its fair share: Abby Johnson, Dr. Bernard Nathanson, Dr. Anthony Levatino and Dr. Carol Everett. In 2019, the pro-choice movement had its most prominent victory to date, with the Rev. Rob Schenck, an evangelical minister, renouncing his pro-life views in The New York Times.

It also wouldn't be the first time one of these conversions had occurred at the expense of the person concerned. In 1997, Eric Craig Harrah, an abortionist and gay man, walked away from his job into an Assembly of God church, where he testified to Christ. Like McCorvey, he joined the speaker circuit and embellished his stories. By 2000, although maintaining his pro-life views, he had renounced Christianity after a grueling turn on the speaker circuit. "Nobody gave a darn how I was. Nobody asked how I was doing spiritually," he told World magazine. "They just wanted me to stand up and talk bad about the abortion industry."

Like Harrah, McCorvey was raised in unfortunate circumstances. Her mother was abusive, her father was absent, and she was involved in brushes with the law from an early age. At 16, she had a violent husband. She was disowned by parts of her family for being queer. In the 1990s, she had already been through a lifetime of neglect.

Advertisement

As a long-time pro-life activist, I believe that abortion is among the most pressing human rights issues of our time. That belief comes from a conviction that all people deserve to live a dignified life free from violence, irrespective of gender, sexuality, race, religion, or location inside or outside the uterus. The gravity of violence against pre-born children makes a legitimate and immense demand on our time and energies.

At the same time, resisting a throwaway culture calls us to be mindful of how we engage with people. It's difficult to know whether the pro-life movement did treat McCorvey unethically. Some activists have called on FX to release the full unedited footage, noting unprompted pro-life statements made by McCorvey in her dying days. The main corroborating evidence for FX's claims comes from Schenck, who was also involved in Operation Rescue in the 1990s. Pavone and Benham deny exploiting her, while also acknowledging a difficult and complicated relationship with McCorvey. We also know that Pavone was mindful about the "big temptation on the pro-life side to view this person as a trophy."

This "confession" shouldn't be hugely surprising for a person who was willing to say on camera whatever it took to make an impression. (We know that McCorvey was compensated by FX for the use of her personal photos in the documentary.) It should, however, be a reminder that behind every talking point, there's a person. Or as she would say: "I am a real person — a living human being."

And that's precisely the point.

[Xavier Bisits previously worked for Aid to the Church in Need International in Iraq. He is based in Washington, D.C.]