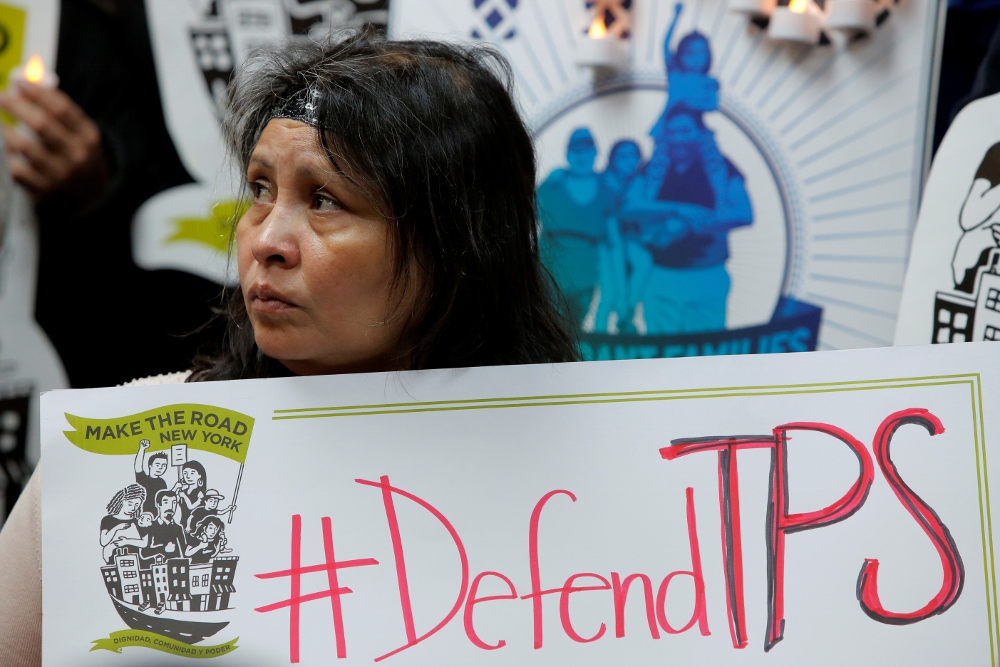

Salvadoran immigrant Mirna Portillo listens during a news conference Jan. 8 at the New York Immigration Coalition in Manhattan following President Donald Trump's announcement to end temporary protected status for Salvadorans. (CNS/Reuters/Andrew Kelly)

Of the estimated 318,860 immigrants who had been shielded from returning to their dangerous home countries under the temporary protected status program at the time President Donald Trump was inaugurated, over 97 percent will soon lose legal status due to a series of decisions that advocates say are based more on anti-immigrant ideology than on facts.

With almost no hope that the Trump administration will voluntarily reverse its decisions or even grant the status to countries experiencing new crises, immigrant rights groups continue to advocate for legislative protections, challenge the decisions in the courts and offer legal aid to individual temporary protected status holders.

"I am aware that we are fighting against a machine that is investing resources in a rhetoric to create fear, to create more uncertainty such as the uncertainty that I have," said Yanira Arias, a national campaign manager for immigrant network Alianza Americas and a Salvadoran immigrant whose temporary protected status will permanently expire Sept. 9, 2019.

"But again, I do believe that collective voices are speaking on a more positive outcome," Arias added, "elevating the contributions that TPS holders give to the United States."

Only 7,070 temporary protected status holders from Syria and South Sudan have had their status renewed under Trump, while 310,540 status holders from El Salvador, Sudan, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua and Nepal have had that status canceled and 1,250 from Somalia and Yemen are still waiting for decisions.

The temporary protected status program is meant to offer work permits and temporary protection from deportation — but not a path to permanent legal status — for immigrants who would otherwise be undocumented.

"TPS has been utilized for numerous reasons by Republican and Democratic administrations," said Lisa Parisio, an advocacy attorney for the Catholic Legal Immigration Network Inc. (CLINIC). The program embodies American and international principles including "non-refoulement, which is the commitment for a country not to return people to countries where their lives or their freedom may be at risk."

The protection is granted when the Department of Homeland Security designates a country as too dangerous to receive returning immigrants due to natural disaster, violent conflict or other temporary conditions, and can be renewed in six-, 12- or 18-month increments, as many times as necessary until conditions improve.

Temporary protected status is only available to migrants who are already in the U.S. when their country is designated — which usually happens very shortly after the disaster that prompts the designation. This arrangement means that those immigrants who receive temporary protected status have been in the U.S. for an especially long time, in some cases decades. Many hold jobs, own homes and have children who are U.S. citizens.

People hold a Honduran flag while sitting on the border fence between Mexico and the United States in Tijuana, Mexico, April 29. The Trump administration is ending temporary protected status for more than 50,000 Hondurans. (CNS/Reuters/Jorge Duenes)

Honduran and Nicaraguan status holders have been in the U.S. at least 19 years, while Salvadorans have been here at least 17 years. (More than 250,000 status recipients come from Honduras, Nicaragua or El Salvador.)

Sudan and Somalia have been protected even longer, nearly 22 and 27 years, respectively, although some status holders from those countries are more recent arrivals since DHS has pushed up the required arrival date in a process known as redesignation.

Trump's administration isn't the first to cancel the status for a particular country. George W. Bush's administration ended Liberia's status in 2007, and Barack Obama's administration terminated the status for Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone in 2017 after putting it in place during a 2014 Ebola epidemic. (Both Bush and Obama maintained protections for Liberians under the Deferred Enforced Departure program, protections Trump ended in March.)

However, the scale of cancellations and the decision-making process under the Trump administration are a sharp break from past policy, advocates said, even raising doubts that any circumstances could lead the administration to designate a new country for the status. Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Florida) has called for Venezuela to be protected and has been ignored.

"What the current administration is doing is unprecedented," said Kevin Appleby, senior director of international migration policy at the Center for Migration Studies. "It seems as though they haven't even considered all the factors on the ground in these countries in making their decision. That has been driven by ideological or political concerns."

Although the program is provided for by U.S. immigration law, and could therefore rebound relatively quickly under a more sympathetic administration, that possibility would come too late for current status holders. Even with the 12- or 18-month delays in termination each country has been granted, their status will expire between November 2018 and January 2020.

The U.S. lacks resources to deport all undocumented immigrants, Arias pointed out, and temporary protected status holders won't be a priority, but losing status will mean the immigrants will be vulnerable to being picked up in raids.

Jill Marie Bussey, director of advocacy for CLINIC, also explained that temporary protected status holders may be especially at risk because many applied for their status "defensively" after coming into contact with immigration enforcement, meaning they may already have removal proceedings in progress that were halted.

"Those wheels in motion go right into work again as soon as the TPS is stripped from them," Bussey said, and they will likely be the "first wave" to be deported.

Despite the administration's lack of transparency, Bussey said, CLINIC is trying to discover how many immigrants are in that position so they can provide legal aid. She and other advocates also recommend immigration screenings for any status holders to see if they might be eligible for legal status through another avenue.

A solution that would protect the majority of those losing status, though, would have to come through legislation or the courts. The administration has repeatedly called for Congress to provide permanent protection for the status holders, a call advocates echo even as they doubt its sincerity or its practicability.

A woman participates in an immigration rally for Haitians Nov. 21, 2017, in New York City. The previous day, Trump administration had announced that Haitians with temporary protected status must leave the country by July 22, 2019, or face deportation. (CNS/Reuters/Eduardo Munoz)

"I don't think in the near future it's realistic, given the political landscape," Appleby said, but administration officials publicly support a path to citizenship. "Whether they were just saying that to get people off their backs or not ... you can point to the fact that they've said that and that Congress should include them in any immigration reform package."

Another avenue of hope for temporary protected status holders is the court system. At least four lawsuits have been filed challenging the cancellation of particular countries' statuses and seeking injunctions preventing DHS from implementing terminations.

All four lawsuits allege racial or ethnic discrimination; some point out disparaging comments Trump made about Haitians and other temporary protected status holders when a bipartisan group of legislators last approached him with an immigration compromise that included legal status for some temporary protected status holders.

The lawsuits also accuse the administration of not following proper procedures in making status determinations.

Recent reports say DHS ignored advice from senior diplomats that some of the countries were unprepared to accept returning immigrants and that the Trump administration pressured officials to end countries' statuses.

"It's not surprising that this is being driven by the White House and by an ideological agenda ... despite advice from career diplomats who know the situation on the ground," said Appleby. "These decisions were made in contrast to our best interests and to that of nations in our hemisphere."

While previous administrations have interpreted the statute that established temporary protected status as allowing them to consider all factors that might make the country dangerous, such as gang violence or subsequent disasters, the Trump administration insists it can only consider recovery from the disaster or conflict that prompted the original designation.

Advertisement

A backgrounder from CLINIC tracks irregularities in the administration's process, such as ignoring information, investigating unrelated concerns and failing to publish essential information for temporary protected status holders in a timely matter.

The reports that are "bringing to the light the diplomats' advice to President Trump not to cancel the program because none of the countries are prepared makes me feel that I am not wrong with the feeling that I have of uncertainty if I am ordered to be deported back to El Salvador," said Arias.

"I continue to have that feeling of uncertainty. What if there is not a solution?" Arias said. "But also it gives me the energy and the hope to continue with the organizing effort."

One of the most concerning aspects of the situation is that the government has disregarded the fact that people's lives could be at risk if they are sent back too early, Bussey said, even though by law the government should consider it. "It's heartless, it's cruel, it's immoral to send individuals back to that type of high level of risk and fear for their lives," she said.

"Very few people who have been here for decades are going to voluntarily want to leave and separate from their families," Bussey added. "There's nothing to go back to, and in fact there's not just nothing to go back to, going back would put their lives at risk."

[Maria Benevento is an NCR Bertelsen intern. Her email address is mbenevento@ncronline.org.]