The Magdala Stone, a limestone box unearthed from a first-century synagogue in Migdal, Israel. (Courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority/Yael Yolovich)

As they jostled to control lucrative and important Middle Eastern spice trade routes between 100 B.C. and A.D. 250, the Roman and Parthian (ancient Iranian) empires have earned Scylla- and-Charybdis-like reputations. So narrow was the room thought to be between them that other faith traditions and people in less-prominent locations have been brushed aside as mere footnotes to the great two.

That's the premise of the Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibit "The World between Empires: Art and Identity in the Ancient Middle East" (at the Met until June 23), whose corrective focuses on what the catalog calls "a constellation of local communities negotiating their distinctive identities in a world of great imperial powers."

It takes more than 80 pages for Jesus to receive his first curtain call, but the exhibit and the thorough catalog address Jewish and Christian religious practices and beliefs at length. The show teases out a potential historical interpretation of Jews, Christians and polytheists living in "peaceful pluralism" on certain sites, like Dura-Europos in present-day Syria. That theory, however, is offset by another of the religions attacking each other in propagandist decorations in their sacred spaces and trying to convert one another. And even if some of the highlighted sites evidenced enviable tolerance, too many in troubled areas have been looted recently by militants aiming to erase other cultures, to make money on the black artifact market, or both.

Christ Walking on Water, a baptistery wall painting, paint on plaster, from the third century, excavated by the Yale-French Excavations at Dura-Europos, in present-day Syria (Courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery)

One of the most fascinating objects in the show is a limestone box, which measures just about 7-and-a-half cubic feet. But the so-called Magdala Stone punches well above its weight. Archaeologists unearthed the monochromatic object in 2009 in a first-century synagogue in Migdal, Israel, (ancient Magdala) on the Kinneret, or Sea of Galilee. Carvings cover the sides of the box, and one image is the first known illustration of a seven-branched candelabrum (menorah) found in a synagogue. This iconography is further notable, because the Second Temple still stood in Jerusalem when this object was made.

Some scholars have linked illustrations on the stone, which is in the collection of Israel's Antiquities Authority, to Ezekiel's prophecy of fiery wheels. The stone may have been the base of a podium for holding Torah scrolls in public readings, or a container for Torahs, per the catalog. But it also carries significance for Christians, even if they neither initially associate the object's home, Migdal (Hebrew for "tower"), with Mary Magdalene's presumptive hometown, nor remember that Jesus preached at Galilean synagogues. Standing before this artifact, it's easy to imagine that perhaps Jesus even stood before a lectern resting on this very box.

One of the sites which the exhibit explores the most in-depth is Dura-Europos, the town which the Parthians controlled in the late second or early first century B.C., but which the Roman military took over around the year A.D. 165. Dura-Europos was destroyed in the mid-third century and wasn't rebuilt, but ironically war and destruction preserved some of its religious buildings for centuries, before looting and the Islamic State destroyed them. (Luckily, many of the important artworks had already been moved to museums for safekeeping.)

Graffito of Clibanarius, plaster from the third century, excavated by the Yale-French Excavations at Dura-Europos, in present-day Syria (Courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery)

Excavations have unearthed 19 religious buildings at Dura-Europos, as well as more than 100 homes, and other kinds of buildings, which collectively "provides a remarkable glimpse of how polytheism and monotheism coexisted during the middle of the third century," notes the catalog. A house-turned-Christian building at Dura-Europos, dated around the year 232, is thought to be the oldest surviving church, and a synagogue, also third century, is nearly unprecedented for its elaborate and figurative aesthetic program. Biblical-themed wall paintings in the synagogue even include the divine hand, which is an exceedingly rare if not unprecedented motif to see in an ancient synagogue, or even a modern one for that matter.

The church and synagogue have been well preserved due to being buried under sand to fortify the city's western wall in the face of a Sasanian (ancient Iranian) attack in the year 256. But before the city was destroyed — and not rebuilt — there is reason to believe that the Christians, Jews and polytheists on site might have interacted more than one would have expected. Debates continue, the catalog notes, whether the faith groups tolerated or tried to convert one another; one view sees what happened at Dura-Europos as "peaceful pluralism."

Dura-Europos' Christian building contains a large assembly space, thought to be where the Eucharist was celebrated, with illustrations of cavalrymen, and a David and Goliath painting decorates its baptistery. Not only are there these two military-themed elements, but a graffito of a mounted soldier in armor carrying a lance and riding a horse, which dates to around the year 232, was found on a wall of the assembly room. It's possible that those receiving the Eucharist, if they took stock of their artful surroundings, were thinking of anything but peace and turning the other cheek.

The baptistery also featured wall paintings of Adam and Eve, the Good Shepherd, the woman at the well, and Christ walking on water and healing the paralytic. An illustration previously thought to have been the women at Jesus' tomb has been recently identified as the Parable of the Ten Virgins, and other miracles of Jesus' may have also decorated the room. The lot "is most likely the earliest securely dated representations of Jesus," per the catalog.

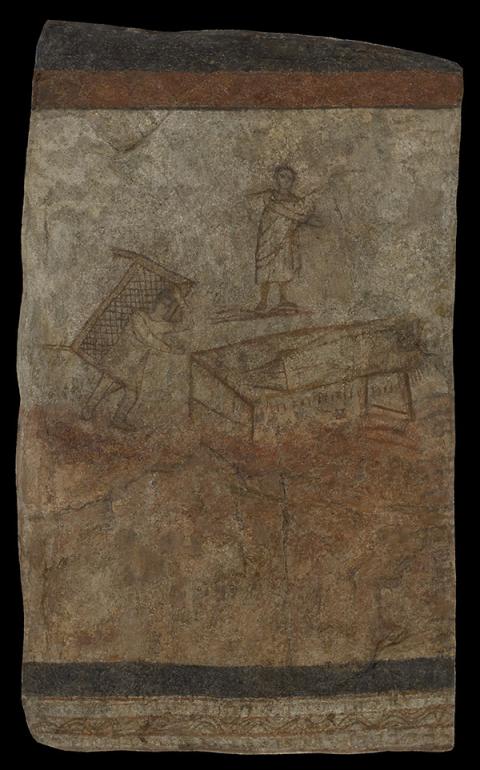

Christ Healing the Paralytic, a baptistery wall painting, paint on plaster, from the third century, excavated by the Yale-French Excavations at Dura-Europos, in present-day Syria (Courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery)

Both the paintings of Jesus walking on water and healing the paralytic (both in the collection of the Yale University Art Gallery) display extensive details in the storytelling. In the background of the painting, disciples stand in a boat, lifting their arms as they look at Jesus, who walks on water alongside Peter in the foreground. The artist has gone out of his way to show the water's movement and to render the contours of the ship. In the other image, Jesus looks down on the sick man lying on his bed. To the left, the artist shares an "after" to the other "before"; the now-healed man carries his bed on his back.

The opposite readings of either religious tolerance or antipathy at Dura-Europos center, in part, on the elaborate synagogue paintings. At a time when the archaeological evidence shows that Jews and Christians were living alongside those who worshipped Mithras, Atargatis, Hadad and Palmyrene gods in a third-century Roman border town, paintings on the synagogue walls showed, in part, temples with smashed idol parts strewn across the floor. Was this meant to provoke polytheists and to contrast the two communities, scholars wonder, cautioning that it's hard to know how much, if any, access adherents of one faith tradition had to sacred spaces of other traditions? And the paintings in the church might also have been meant to shed theological daylight between Christ's miracles and the pagan sacrifices made in nearby temples.

Differences in the architecture of the sacred spaces are also noteworthy. The Jewish and Christian buildings were repurposed homes, while the pagan temples were initially built as such. "Synagogues and churches represented something different: spaces designed for gathering and worship rather than defined by the presence of a divine statue or relief," the catalog notes. It adds that Christian buildings of this period were also laying the foundations for even future medieval cathedrals and modern churches.

Early Christian architecture incorporated towers, the curators note, but their floor plans repurposed meeting halls, with long rows of columns and a semicircular apse (the Latin word "basilica" here predates Christianity). As the early Christian artists and patrons were adapting and adopting secular Roman architectural elements to forge a new Christian art, they were also looking out on their non-Christian neighbors with a sense of empathy, of competition, or a mixture of both. More than a millennium and a half later, that's about how things remain.

[Menachem Wecker is a freelance reporter in Washington, D.C.]

Advertisement