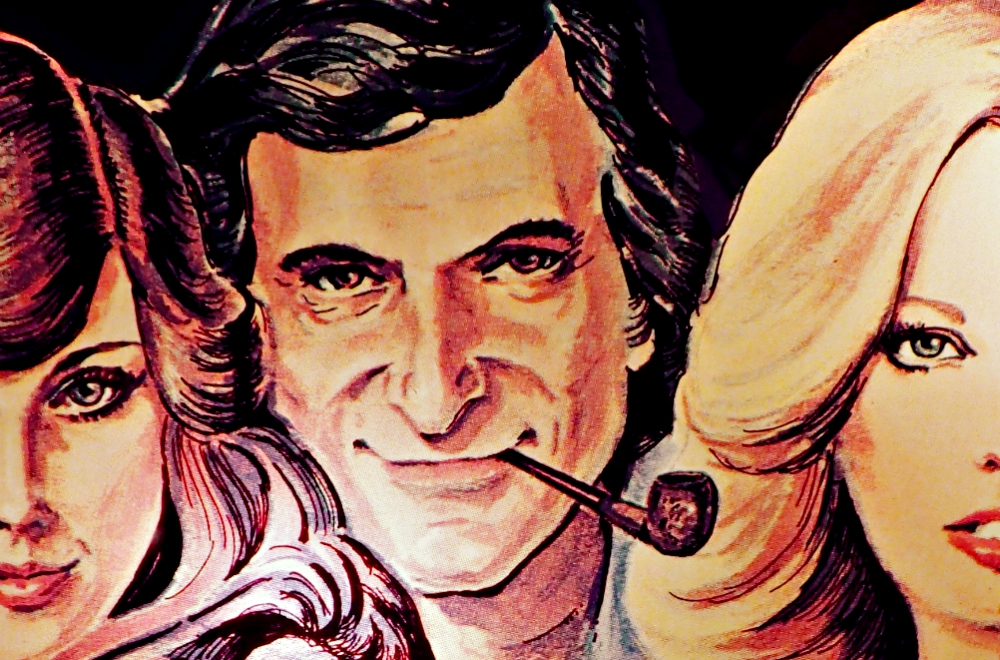

Hugh Hefner, depicted on a pinball machine (Flickr/Michael R. Perry, CC BY 2.0)

Hugh Hefner aspired to free us from our inhibitions and the guilt we suffer from self-indulgence. Not just to liberate our libidos but to remove anything that stood in the way of consumption. To echo BASF's television ad, Hefner didn't invent materialism — he just promoted it when the time was ripe. The post-World War II boom was gaining force, young executives were on the rise and rock-and-roll heralded a readiness to break with moral restraints.

Hefner seized that opportunity to increase that momentum as its pitchman. He encapsulated it in his signature project, Playboy magazine, and superbly played the role of its enabler. Sleaze and greed had been in no short supply but for the most part were associated with mobsters and degenerates; the cravings of self-described respectable classes were restrained by warnings on sex, spending and self-promotion.

Hefner took the cues: He couched those passions for worldly conquest as a figure that fit the yearnings of postwar American male, prideful but modest, ambitious but mannerly, sexually adventuresome but not libertine (Hef always struck me as anything but rakish).

The message was perfectly pitched: a man resembling a local bank manager privately living out the fantasies of possessiveness. Of luxury cars, penthouses, celebrities and, of course, women, having broken the stranglehold of ancient prohibitions to lay hold of the unfathomable riches of an emerging America. For good measure, he often adopted tasteful silk pajamas and smoking jacket to cast himself as the host of America's bedroom full of delights. As with everything in his repertoire, he masterfully packaged old pursuits of desire in "acceptable" wrappings.

To borrow a concept from the counseling field, he gave the up-and-coming affluent classes "permission" to cast aside the "thou shalt nots" and enjoy the fruits of the earth to their hearts' content, whether that be Italian suits or as many amorous affairs as they could manage. Material things were there to use, not ration.

To rationalize his pass over into this promised land, Hefner assaulted religion as the cause of his repression, ingrained by cold, strict Methodist parents, emphasis Methodist. By inference, the entire nation had been bound in a moral and emotional straightjacket by the long arm of Puritan tyranny and he was by rebelling against it on behalf of the prisoners.

He undertook this attack in the form of a "Playboy philosophy," which consisted of repeated variations of the Freudian theme that religion was a human invention that fashioned a god as a distant father image and acted as a device to control the masses (Marx chimes in here too). Freud at least found some use for it as a means of keeping instincts from getting out of hand, but to Hefner's shallower thinking, it served only to make his early decades miserable.

The "philosophy" reflected a get-me-out-of-here mood among many who had emerged from the war with broader tastes for life and possibilities for attaining them. Religion was widening its scope, too — including Methodism, in which I was raised — to encompass fuller visions of human rights, including sexual expression. The morality of previous eras, which derived from society and religion, may have served a purpose and could now grow to suit new circumstances.

But Hefner, like most others, including churches, had wrongly conflated theology and ethics by reducing religion to morals and missing the larger spiritual dimensions. At any rate, the Playboy influence played into an anti-religion trend that was ready to blame our worst personal ills at the foot of the altar.

Advertisement

So the critique was sophomoric and full of holes but appealing to a wide swath of people who were looking to burst loose from harsh rules, which too much religion did wield, but in shedding that manifestation of it unfortunately missed a great deal of the underlying faith and trust that brought healing and consolation. At the same time, the traditions did embody a consciousness that runs counter to hedonism and selfish individualism and, yes, greed, no matter how much religions themselves violate that wisdom.

Hefner did serve as a vehicle to bring the alternative to that Christian consciousness front and center at the time it was most tempting. The country did become more like the one he practiced and promoted. Consumerism has become stronger, even through economic disasters, and personal freedom continues to break new boundaries.

Playboy helped usher in this longing to be unfettered, and there was considerable need for it on many fronts. Woman and minorities were trapped not only by force but by unexamined "laws" that oppressed them. Many exploited workers, then and now, needed rescue.

To dwell on sexuality alone, as Hefner mostly did, with nods to women's equality, narrows the cause to self-interest. To build an empire essentially on religious bashing and specialized strategy to make consumerism OK doesn't rank among my great movements of history.

But he did succeed in our national terms, and he earned the respect of many who felt justified by his role model, including those influential writers and leaders who were well-paid by him to give the sales pitch some gravitas. Without Hefner's largesse, Playboy's readers would probably never have had the opportunity to read great writers, so they looked there first.