People pray during a Pontifical High Mass Feb. 15 at St. Vincent Ferrer Church in New York City. The liturgy preceded the third annual Lepanto Conference, a one-day event featuring speakers who discussed the history, beauty and sacredness of the traditional Latin Mass. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

A recent New York Times article on "Weird Christianity" undoubtedly left some Catholics perplexed as to why all these young people are flocking to Latin Mass. Critics fear elitist anti-modern tendencies. Could this step backward into a world of bells, incense and traditional pre-modern moral norms impede the progress made since medieval days?

While traditionalism can surely lead Catholics to retreat into the past and hide from the modern world, it can also serve as an impetus to engage more deeply with the wounds and needs of today's world. The focus on beauty and materiality should inspire us to go out into the world and encounter Christ in the flesh, in the margins, as Pope Francis says, and discover how liturgy and spirituality are connected to the needs of those around us.

My first attraction to Catholicism began when I took a required philosophy of human nature course as a freshman at Fordham University. My professor, who was in her early 80s, was the first person who took my questions about life's meaning and ultimate truth seriously — and who spoke about these matters with such gladness and certainty. "You all exist for a purpose," she would say, "and it is your duty to find out why." I needed to know what was behind this woman's bold assertion.

During office hours, I shared how bewildered I was by my seemingly endless existential questions. "Stephen, you're not crazy," she told me. "It's just that God desires a deeper relationship with you. That's all."

Soon after this, I came across a group of students who met weekly to discuss their questions and experiences through the lens of their Catholic faith. They were not ideological about their faith, nor did they reduce it to mere sentimental, feel-good pietism. Rather, they took it seriously and wanted to know what it had to do with every aspect of their lives — from the beauty of being together at a party to the toil of challenging school work.

At a certain point, it occurred to me that all of these people I was so attracted to happened to be Catholic. A couple of days later, I saw that the parish across the street was beginning Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults classes. In a matter of months, I finished the catechumenate and became a confirmed papist.

Advertisement

As I started exploring Catholicism's different spiritualities and devotions, I quickly found myself enamored by the Latin Mass and traditional piety. I fell in love with its richness, which was slightly reminiscent of the byzantine liturgy I had grown up with.

I soon realized I wasn't the only millennial attending Latin Masses.

It's true that "Weird Christianity" draws in many privileged, (upper-)middle class, mostly white, millennials, who — like me — grew up sheltered from the hardships and injustices that plague our society. But this bourgeois suburban setting proved to be a breeding ground for existential emptiness.

The combination of feeling like you're entitled to things you've never earned, being told that you can be whatever you want to be, and that all it takes to be happy is to "be yourself" conceals a darker reality. Beneath this façade was a dull, ambiguous road that leads to nothing in particular. Who cares that I can do, have and be whatever I want? If there's no "real" point, no objective truth, can life have any real meaning?

This also colored my experience of religion. Watered-down Christian liturgy and doctrine only reinforced this elitist bourgeois worldview. At my dad's Catholic parish, the drab liturgy and "Jesus wants you to be nice to people" homilies did little to shake up the complacency of the privileged parishioners. And while I was enamored by the liturgy at my mother's Greek Orthodox parish, I experienced its beauty to be mostly irrelevant to my everyday life.

Even worse, the moral and spiritual landscape of suburbia didn't seem to take into account the deepest yearnings of the human heart. The infinite desires for beauty, justice, truth and love are repressed by this sedated, cozy suburban ideal. It never dared to shake up the social, moral and spiritual status quo that allowed us to live in a bubble of comfort. You can live a nice lifestyle, as long as you're "a good person." This "gospel of good will" never veered to extremes; it always seemed to stay put in the middle of the road.

But the path in the middle of the road led to apathy and nihilism. This is why so many of my college classmates and I ran as far as we could from it and instead flocked to extremes. Most of my classmates opted for a political route, some to the left — taking on a socialist outlook centered on the rights of racial and sexual minorities — while others went right — fighting for the crumbling causes of national identity and moral values. Others ran down the Dionysian road of pleasure, seeking new sexual adventures every night, or experimenting with drugs and alcohol.

None of these "alternate routes" held much traction for me. Instead, my foray into the realm of the traditional Catholic sensibility seemed to fill those cravings.

Many people flinch when they hear about traditional liturgy and spirituality because they associate it with antiquated views of women, colonialism or anti-modernism. I acknowledge that much of pre-modern Catholicism is tangled up with ugly systems of oppression. But I've found that both traditional spirituality and morality have not only imbued my life with a more tangibly definitive meaning, they have also made me more sensitive to social injustice and the suffering of others.

The demanding moral teachings of Christianity, modeled on the kenotic love Christ demonstrated on the cross, have reshaped my outlook toward life from one of self-seeking comfort to self-sacrificial charity. The witness of people like Dorothy Day, who recognized the connection between traditional doctrine and liturgy, and proximity to those on the margins, speak volumes. Accused of being both a radical communist and a conservative prude, Dorothy believed that personal holiness — bolstered by her readings of early church fathers and medieval mystics — and fidelity to church teaching were crucial to creating a more just social order.

I am also inspired by more contemporary examples of people like Eve Tushnet who view chastity and celibacy not as obstacles to intimacy, but as entry ways into a deeper mode of living in relationship with others.

Citing the work of queer literary critic Frederick Roden in a 2009 article "Romoeroticism," Tushnet highlights the way that the liturgical, aesthetic and sexual ethos of medieval Catholicism drew in troves of gay Brits in the Victorian era "who responded strongly to Catholicism's physicality." She continues:

The incense smoke and flaking paint, the hint of cannibalism that recalled the Church to Her disrespectable origins, the kneeling, and the statues called to gay men and women. If you're persecuted for your reaction to gender and physicality, you may become intensely aware of bodily realities; and Catholicism, alone in the mainstream Western religious landscape, kept insisting that bodies were both important and bizarre. We alone kept saying that the flat white wafer in the priest's hands might shiver at any moment into raw and bleeding human flesh. We alone made Communion a horror story.

Tushnet's words resonate deeply with my own personal experience. Older forms of liturgy and spirituality tend to place greater emphasis on beauty, the body and the material realm as a whole. The bells and incense at Latin Mass, the gory, baroque Spanish crucifixes, and eucharistic processions have made tangible the abstract ideals we believe in in a way that the felt banners and David Haas hymns in my dad's parish never did for me.

Archbishop Michel Aupetit of Paris uses a censer as he celebrates the annual chrism Mass at historic St. Sulpice Church April 17, 2019, in the wake of the massive fire that seriously damaged the historic Notre Dame Cathedral. (CNS/Paul Haring)

There was something about meditating in front of the statue of Christ taken down from the cross in the formerly Italian (now Puerto Rican, Haitian and Nigerian) parish in my grandparents' old neighborhood that spoke to me. Maybe it's his body's lifelike musculature, the paint on his feet that has worn down from countless people rubbing them — imploring Christ to reveal himself in their daily trials — or his lifeless gaze, which seems to call out for someone, anyone, to console him in his agony.

This Jesus is close to my suffering. This Jesus affirms that — yes, life does have a purpose, there is a light in the darkness, there is hope within your shortcomings. Not only this, but gazing into his suffering face has made me more attentive to the suffering of those around me. This is what I find to be most compelling about "Weird Christianity." My experience of this unusual brand of Catholicism has inlaid in me a yearning for the virtues of humility, listening and attentiveness.

These virtues are especially necessary for those Weird Christians who are among our society's more privileged echelons. We need to learn how to listen and learn from those who are less privileged, without imposing our opinions or experiences.

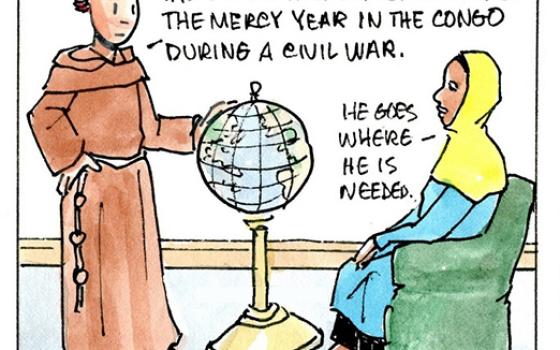

I am immensely grateful for those who have taken the risk of telling me their stories and sharing their sufferings: homeless people I've met through a soup kitchen run by a local community of Franciscan friars, the students at the high school where I teach — many of whom have dealt with instances of racism and countless hardships due to immigration struggles — and my own elderly grandparents who are facing intense physical pain as they near the end of their lives.

This brand of spirituality that highly values the physical has allowed me to discern Christ's face keenly in the suffering of others. These experiences have made me want to understand the experiences of those who face social injustices. They've forced me to question my own privilege and the extent to which my lifestyle contributes to the suffering of others.

Yes, traditional spirituality can lead us into the temptation of making an idol out of the past and hiding from the secular world. Instead, I would urge "trads" to rely on Francis' image of the church as a field hospital and enter into the world with our alternative vision. Let's consider what a great gift we have in the "weird" expressions of our faith — a gift our weird and wounded world is desperately in need of.

[Stephen Adubato studied moral theology at Seton Hall University and currently teaches religion in New Jersey. He also blogs at Cracks in Postmodernity on the Patheos Catholic Channel.]