Polish Archbishop Wojciech Polak of Gniezno speaks during a news conference in Warsaw May 22 after bishops met to discuss steps the Catholic Church will take to tackle the problem of clergy sex abuse. (CNS/Reuters/Agencja Gazeta/Slawomir Kaminski)

When Polish Catholics marked 40 years since Pope John Paul II's first home pilgrimage in early June, it was a moment to look back on their church's legacy of much-lauded struggles for justice and human rights.

Today, with that legacy tarnished by a spate of controversies and scandals, some Catholics fear its authority and prestige face serious erosion, whereas others insist the church has come through disasters before, including those of its own making.

"The church has asked people to pray, reflect and do penance — it doesn't really know how to react to failures and never tackles the root causes," Malgorzata Glabisz-Pniewska, a senior Catholic presenter with Polish Radio, told NCR. "It senses it's too well rooted in Polish society and culture to be seriously damaged by negative publicity. This time, things could be different, though it'll clearly have to respond effectively."

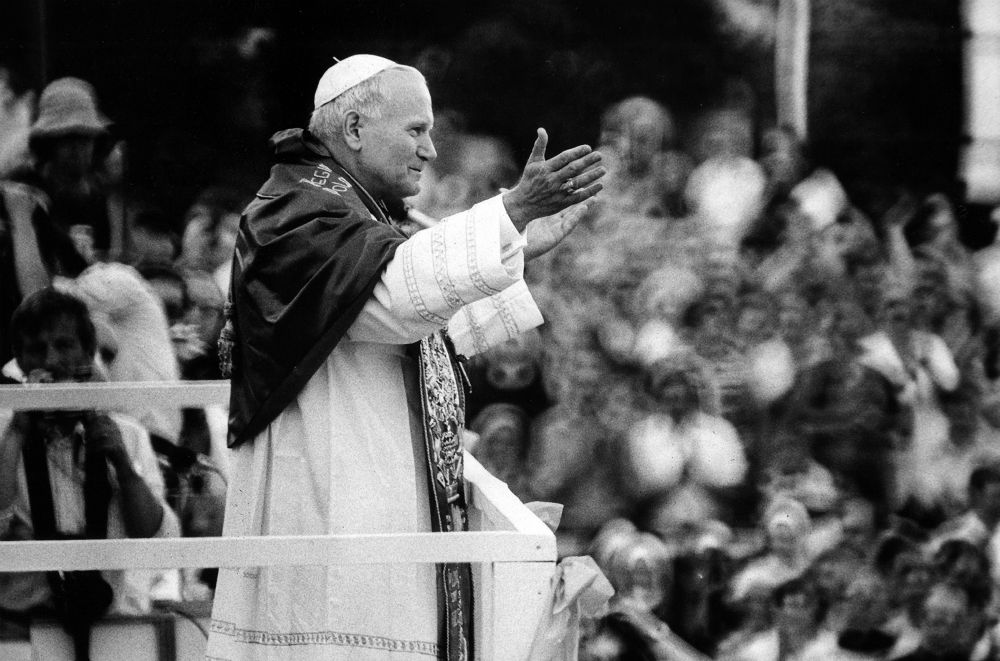

In 1979, the newly elected John Paul II preached 32 homilies before 13 million enthusiastic people in the space of a week, in what was to be the first of nine visits to his Polish homeland.

The pilgrimage included his famous invocation of the Holy Spirit in Warsaw's Victory Square, and was widely credited with inspiring the Solidarity union's uprising against communist rule in August 1980. It marked the start of great epoch for the Polish church, which led on to the peaceful restoration of democracy, pluralism and the rule of law a decade later.

Solidarity's victory in semi-free elections, whose 30th anniversary was also marked in early June, was followed by years of bitter struggle over the church's place in the new post-communist Poland, and over the values the country would live by as it gained in stability and prosperity.

Pope John Paul II greets hundreds at the monastery of Jasna Gora in Czestochowa during his 1979 trip to Poland. (CNS/Chris Niedenthal)

The church survived the loss of its key authority with the Polish pontiff's death in April 2005; and it weathered many storms — over abortion and school religion, its infiltration by communist informers, and its profiteering from land and property restitutions.

To this litany has now been added drastic revelations about clerical sex abuse. It was a crisis waiting to happen, worsened by prevarications, and it finally exploded into the open this May, when a TV documentary exposed how endemic abuse had long been ignored and covered up.

"This film has played a key role as catalyst for a cleansing process. It's no longer enough to seek improper, superficial, communist-style ways out, by looking for excuses and allies to help us," explained Jesuit Fr. Adam Zak, the church's national coordinator for child protection. "We have to admit we made mistakes and failed to follow the right path, proudly believing we were better than others and hiding behind our historical experiences of persecution."

When Zak was appointed in 2013, media accusations of inaction were already multiplying, and Poland's Catholic bishops had adopted and updated their own abuse guidelines in line with Vatican directives.

And by last September, all 43 Catholic dioceses had their own child-protection officers, while hundreds of clergy had been trained in prevention and counselling by a special church center in Krakow.

Not even this could deter a barrage of accusations, which reached a head when a salacious anti-clerical film, "Kler" ("Clergy"), broke cinema box-office records last fall.

In November, the bishops issued a statement, apologizing to "God, the victims, their families and the church community" for clerical abuse and pledging "illumination, strength and courage" in combating the "moral and spiritual corruption" that had caused it.

And in February, on the eve of a Vatican summit on child protection, the bishops' conference president, Archbishop Stanislaw Gadecki of Poznan, agreed for the first time to meet a group of unnamed abuse survivors.

However, in a report the same month, a victims' support foundation, Nie Lekajcie Sie ("Do Not Be Afraid"), accused 24 church leaders of violating secular regulations and canon law by "concealing clerical crimes and moving pedophile priests from one parish to another."

The report named Cardinal Kazimierz Nycz of Warsaw, Archbishop Leszek Glodz of Gdansk and retired metropolitans from Poznan, Przemysl, Szczecin-Kamien, Warmia, Warsaw-Praga and Wroclaw. It listed 384 victims and 85 convicted priests in a "Map of Clerical Abuse," but said most victims had not been included because of fears of "social ostracism."

Though presented at a Rome press conference and personally handed to Pope Francis on Feb. 20, the report was bitterly attacked in the Polish church, with dioceses and religious orders issuing adamant rebuttals.

Polish bishops attend a news conference to release the church's first clerical sex abuse report March 14. In zucchettos, from left, are Bishop Artur Mizinski, secretary-general of the Polish bishops' conference; Archbishops Marek Jedraszewski of Krakow; Stanislaw Gadecki, bishops' conference president; and Wojciech Polak of Gniezno. (CNS/Reuters/Agencja Gazeta/Adam Stepien)

The secretary-general of Poland's Conference of Higher Female Superiors, Mother Jolanta Olech, revealed to the church's Catholic Information Agency, KAI, that nuns had also been molested by Catholic priests, while the city council in Gdansk demolished a statue of Fr. Henryk Jankowski (1936-2010), a one-time Solidarity hero, after his pedophilia was exposed.

At a March plenary, attended in Warsaw by Vatican Secretary of State Cardinal Pietro Parolin, the bishops' conference appointed Archbishop Wojciech Polak of Gniezno, the Polish Primate, as its first child protection delegate, and published its own report, listing accusations against 382 priests over three decades.

The document said 44 percent of claims had been investigated by state prosecutors, with around half resulting in convictions, although only a quarter had resulted in defrockings and only a small fraction in damages for victims.

It conceded there had been "a certain ignorance" about church rules on abuse, and said "differences of reliability" between Polish dioceses and orders in responding to inquiries had necessitated "additional monitoring."

The report was widely criticized for alleged selectiveness. And in May, a major blow was struck by the TV documentary, "Tylko nie mów nikomu" (Just Don't Tell Anyone"), made by investigative journalist Tomasz Sekielski.

Sekielski's moving two-hour epic attracted 20 million views within a week of its May 11 YouTube posting. It linked abuse with secretive church structures and showed the evasive behavior of perpetrators when confronted by victims. It also made accusations against Fr. Franciszek Cybula, former chaplain to President Lech Walesa, and charged several Catholic prelates of concealing clergy from law enforcement and failing to act when abusive clergy continued celebrating Mass and working with children despite being sentenced and dismissed from the priesthood.

Advertisement

And it was well-timed, appearing just two days after the pope's letter, Vos Estis Lux Mundi, established new procedures for holding church leaders accountable for abuse.

The bishops' conference responded with a message to all parishes on May 26, thanking the filmmakers for exposures which had "convulsed the church community," and lamenting the church had "not done everything" to counter the "violent and brutal despoilment" of children.

"There are no words to express our shame over sexual scandals involving clergy — they cause great outrage and demand total condemnation and severe consequences for the criminals," the message said. "This film, presenting the perspective of those harmed, has alerted us to the magnitude of their suffering, and everyone with sensitivity will feel pain, emotion and sadness. We thank everyone who had courage to talk about their suffering."

The bishops promised to appoint a legal team to analyze the causes of abuse, set out measures for implementing the pope's call for new procedures, and improve awareness and communication in Catholic communities. But their message made no mention of material help or compensation for victims and limited its pledges to "psychological, legal and pastoral support" and offers of "sympathy and sensitivity."

Several dioceses and religious orders have issued separate statements about the film's allegations, and issued their own protection guidelines for Catholic parishes, schools and other institutions.

A woman places a candle during a prayer vigil at Pilsudski Square in Warsaw, Poland, April 2, 2014, the ninth anniversary of the death of Pope John Paul II. (CNS/EPA/Bartlomiej Zborowski)

Church support dropping

Meanwhile, Bishop Piotr Libera of Plock, who was harshly criticized, is to withdraw for six months to a closed monastery to "pray for the church," and the controversial Archbishop Glodz of Gdansk has apologized after initially denouncing the documentary as "garbage."

Some Catholics have vowed to boycott Masses celebrated by other implicated figures, including Archbishop Marek Jedraszewski of Krakow, while at least one prominent figure, Msgr. Andrzej Szostek, a former Catholic university rector, has called on the whole bishops' conference tender its resignation to the pope, following the example of Chile's bishops in May 2018.

Dire predictions have continued about the impact of the film by Sekielski, who says he's negotiating a distribution deal with Netflix and planning a follow-up in October.

In two early June surveys by the government-controlled CBOS agency, the Polish church's public approval rating had dropped to a 24-year low, with just 48 percent of citizens viewing its activities as positive, while the proportion of youngsters declaring themselves believers had dropped over a decade from 81 to 63 percent.

For the first time in a country known for its unquestioning adulation for John Paul II, questions have been asked in the Polish media about the late pontiff's failure of tackle abuse, forcing Cardinal Stanislaw Dziwisz, his former assistant, to issue repeated statements in his defense.

A window in Krakow's Catholic curia from which the saint addressed applauding followers has now been bricked up, while in May a giant statue of the pope was covered over at the Marian basilica of Lichen because it also depicted the basilica's 91-year-old founder, Fr. Eugeniusz Makulski, who was branded a pedophile in Sekielski's film.

There's no doubt the church faces a real challenge now — how to learn from its mistakes, and humbly reassure society," Zak, the child protection coordinator, told the KAI agency on June 10. "There must be a change of mentality and activity so the faithful are no longer ashamed of their pastors, and pastors of their predecessors. Priests must see which skeletons lurk in their cupboards — and if they give the right signals, there's a great chance some deep purification will occur."

Cardinal Kazimierz Nycz of Warsaw, Poland, waves during the Three Kings parade in celebration of the feast of the Epiphany in Warsaw, Poland, Jan. 6, 2015. (CNS/EPA/Jakub Kaminski)

Beneath the surface, however, there are doubts.

Some Catholics think the Polish church's crisis-management skills will offset the need for any drastic changes, and that if any bishops resign, it'll be for age and health reasons rather than from any admission of guilt.

With a model of mass religiousness inherited from the communist era, the church thrives best when under attack, and has a long-proven track record of rallying popular support against opponents.

By commending and thanking Sekielski for his film, the bishops have footed critics who expected a torrent of denials, and implied they were previously unaware of the extent of abuse.

Meanwhile, by encouraging prayers and acts of penance, they've also diverted attention away from practical action, and created conditions for a strong fight-back once public opinion moves on.

There are signs this is already happening.

Bishops expected say problem is marginal

Poland's governing center-right Law and Justice party, PiS, was victorious in crucial May 26 European Parliament elections, despite its closeness to the church. And when traditional first Communion Masses and processions took place nationwide, there was no sign of any fall in numbers.

With the proportion of clergy abusers put at 0.8 percent by the KAI agency in March, the bishops will seek to persuade Catholics the problem is marginal and that they're doing more to tackle it than teachers, doctors and other groups.

"We're experiencing a certain turbulence, but it doesn't threaten the functioning of our community," Bishop Romuald Kaminski of Warsaw-Praga assured a congregation of priests and lay missionaries in early June, after claims he'd recently reappointed a priest, Fr. Mateusz Matuszewski, who'd been dismissed in 2014 for pedophilia. "For whole decades, the church in our fatherland has been viewed as one great grey unity, whereas recent incidents have shown up fractures and diversities towards God, the commandments and the community. But the decisive majority of our people are true witnesses of Christ, who can be counted on to stay loyal."

Franciscan monastery in Katowice Panewniki, Poland, 2010 (Wikimedia Commons/Karol Glab)

The church's harshest opponents will go on fighting against it, whatever it does to assuage criticisms, while the church's most diehard supporters will go on defending it through thick and thin.

In such polarized conditions, it's the great majority of ordinary priests and parishioners, untainted by any scandals, who suffer most — and whose service to the church risks, in the words of the Polish bishops' May 26 message, being "obscured by the sins of individuals through collective responsibility."

With Catholics making up 85.8 percent of the population of 38 million, according to a 2018 statistical yearbook, the Polish church still provides a large proportion of all vocations in Europe, and is needed as a well-organized, articulate voice in international moral and religious discourses.

But it also needs to be a modern church — open, reliable and trusted — if it's to rise above the damage inflicted by a tiny corrupt minority.

"If our church does decline, it won't be because of abuse scandals, but deeper secularizing trends," Glabisz-Pniewska, the Polish Radio presenter, told NCR. "Certainly, contests are being played out discreetly in the ranks of its hierarchy, as younger figures emerge with a different narrative on past and present events, and a firmer grasp of the need to improve the church's image. But for now at least, the church is too strongly grounded here for any substantial change."

The PiS government has proposed a state commission on pedophilia, backed by criminal law amendments imposing up to 30 years' imprisonment for child abuse.

Just what the church will do in the long term to ensure greater accountability and honesty among its clergy remains to be seen.

[Jonathan Luxmoore covers church news from Oxford, England, and Warsaw, Poland. The God of the Gulag is his two-volume study of communist-era martyrs, published by Gracewing in 2016.]